Alex Pretti Was Murdered by the State

To insist otherwise is to volunteer as a propagandist for authoritarianism

You have already been introduced to this essay’s “thesis statement”. But before coming back around to its narrow defense, we will have to do some significant ground-clearing.

I have never understood, let alone been able to respond to, multiple-choice questionnaires soliciting my “political views”. The problem with being asked to say whether I am “pro-immigration” or “pro-choice” or the like is that there is always an overarching meta-issue, left totally unaddressed by the solicitors, concerning what Isaac Levi once described as “the most neglected modal” — to wit, feasibility.

Along with a reasonable concern to fix this modality, the respondent obviously also has an interest in knowing what sort of time-frame one should have in mind. In an absolute sense I would like to live in a world without borders, without abortion, without prisons, without police, and indeed without states. But I don’t think it makes sense, in the present state of the world, to say that I am an advocate of open borders or prison abolition, and I am definitely opposed to criminalizing the choice to terminate pregnancies made by girls and women in a society already so hostile to them, and so dead-set on making it as hard as possible to raise happy, healthy, prosperous children.

Still, I really do believe that prisons, wars, abortions, capital punishment, industrial agriculture, and many other things many of us take for granted as inevitable constitute real moral failures of humanity. For in all these cases there is a being of real moral interest —even if it is “just” a fetus, or indeed “just” a disconsolate calf torn from its mother, or “just” an enemy soldier or “just” an ear of Monsanto corn—, from whom (yes, whom!) the love due to them as creatures of God has been sinfully withheld. (Capital punishment, in contrast with all these other issues, is a problem that, given the minuscule numbers involved, could be solved tomorrow. There simply is no basis for believing that the state has any sovereign power over any human life. It should be abolished immediately.) It is the work of serious thinkers to envision a world without such withholdings, and to begin to lay out drafts of plans to get from here to there. So leave us alone with your mind-numbingly simplistic questionnaires, I always want to respond, and come help us think instead!

What I have said so far points at one of the reasons why I often give the impression of evading the pressing political issues of our age. I believe we have a duty —or at least anyone who sets themselves up in the world as an intellectual, as I am bold or foolhardy enough to do, has a duty— not to speak in slogans, not to serve as vessels for the speech of others, but instead to struggle to come up with and to share genuinely new ways of comprehending the world, whether through rational argument or creative vision. To this extent I find it gravely unfortunate that our new media technologies have effectively imposed on us an expectation of universal punditry, so that it is often simply assumed that to have a public presence at all, even if it is nothing more than a collection of a few hundred virtual friends or followers, entails, as part of the “job”, issuing regular statements on every new inflection of our rolling global polycrisis as if we were all the spokespeople of august institutions. I believe that this new system has been extremely harmful, and indeed that it bears significant responsibility for bringing the polycrisis into existence in the first place.

It is a great irony that just as actual democracy seems to be receding across the globe, even as a mere aspiration, a spurious semblance of debate at least has been hyper-democratized beyond any useful proportions. One result of this new discursive free-for-all is that the exchange of opposed ideas takes on an almost automated quality — indeed with the rise of chatbots it now often is automated. When human beings jump into the fray to interject their own stubs of ideas, they generally find themselves capable mostly of ad-hominems, among which a perennial favorite is the accusation of hypocrisy. Politics is consequently reduced, by people who understandably do not wish to be on the receiving end of such accusations, to a public performance of their own purity. And thus we get the absurd figure, for example, of the militant vegan who scrutinizes ingredient lists for trace amounts of animal collagen, or the environmentalist who scrupulously separates the trash into its various subspecies as if that were the ritual that could be hoped to hold the cosmos together.

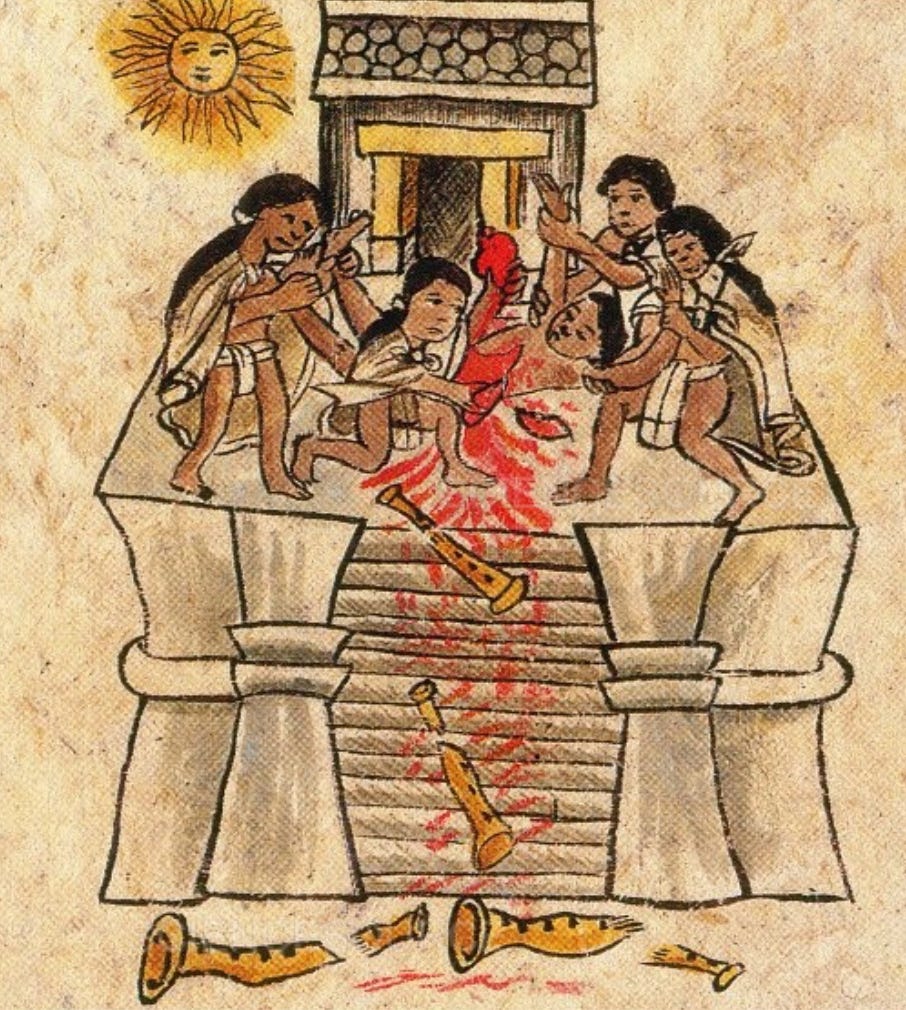

But these are really just examples of what might best be seen as the comprehensive privatization of our responsibility towards one another and towards nature. I myself eat the cheese made from the milk made by the mother cow for its now disconsolate calf, who will soon be rendered into veal. This, along with many other things I do and will not reveal here, makes me particularly impure. But my point is precisely that politics, conceived as the performance of individual purity, the anxious demonstration to others and to oneself that one has transcended all hypocrisy, can never be anything but a dead end. There simply is no purity in this fallen world. It was in recognition of some such truth that the ancients performed their sacrifices before eating animal flesh — a ritual complex that really did, in some profound sense, hold the cosmos together.

It is in view of such convictions as these —or perhaps of such temperamental traits— that I remained consistently at odds with the great majority of my peers throughout the years, roughly 2015-2023, of “progressive” ascendancy, call it what you will, in the western world. It was really all very simple for me: I did not want to serve, indeed could not serve, as a vessel for other people’s speech. And that, when it comes down to it, really is what that regime expected of us. As a result, and much to my displeasure —for I really do long to be universally loved!—, I found myself willy-nilly in the much-despised role of the “Well, actually…” type of guy. But now, looking back, I do think of those years with a certain amount of pride (an emotion I know I should not allow myself to wallow in for long): I managed to maintain my integrity, and I’m confident in challenging anyone, now, to find anything I said during those years that might be interpreted as a capitulation to the reigning order.

I did indeed publish an awful lot of work in an anti-racist key during those years. But of course I did. I’m an anti-racist. Racism is for ressentiment-driven yokels and losers. While I’m often uncertain as to how to describe my class origins, other than to say “it’s complicated”, one data-point that does seem relevant is that during the first eighteen years of my life hearing the n-word, spoken by white people with a hard “r”, was practically an everyday occurrence. This is, to say the least, no longer the case. I can recall once going over to the apartment of some kid whose brother was the friend of an Okie girl whom I had taken to following because she had smiled at me sweetly. There was no furniture, there were bags of Fritos and empty beer bottles strewn across the carpet, and the only decoration was a giant American flag nailed to the wall, with a hammer hanging on nails next to it. When he saw me looking at the hammer, he laughed and declared: “That there’s my n****-beater.” (Anyone who insists that America was not built on racism should ask themselves, honestly, why these two particular ornaments paired so naturally on that wall, from the point of view of our amateur interior decorator.) Political consciousness is slow to emerge, and I confess that my primary thought on that occasion was not exactly shaped by the reading I had not yet done of the canonical works of Black liberation or of the Civil Rights movement. My thought, rather, was: “Oh man, I’ve got to find myself a classier crowd!” And I suppose I did.

Part of the legacy of this experience, for me, is to remain ever conscious of the fact that racism, among all the other reasons to reject it, is in the end a marker of low status. It’s something one aspires to get away from not only because it is a false model of reality, but also as part of a much broader aspirational complex. The aspirational quality of it would become particularly transparent under the ideological regime of 2015-2023, when, at least for white Americans, social media and institutional pressure would stimulate a sort of competitive public performance of individual anti-racism, such as to make the separation of one’s household recycling appear as a much more primitive art-form by comparison.

Under the regime in question, it is not surprising that whatever I might have said or written in an anti-racist key could not pass muster with the regime’s ideological enforcers, since it did not involve all the ritual prostrations that would announce to the assembled audience not only what I believe, but also what side I am on. I continued to think of myself as some kind of humanist universalist liberal — and I still do, with some significant caveats. But I always felt as if they saw me as hiding something. If that is what I was doing, it may be because it was only towards the tail end of that regime’s reign that I began to understand the real nature of my difficulty in going along with it. The difficulty, namely, is that I am just fundamentally not a Schmittian, I do not make a friend-enemy distinction, and to that extent I really, truly do not have a side.

This realization has only deepened my commitment —again, with significant caveats— to liberalism. I can recall, as a moment of something like revelation, seeing a post on Twitter, circa 2024, from one of those right-wing Catholic guys — Patrick Deneen or Adrian Vermeule, I don’t recall. I believe it was a photo of a street somewhere in London, perhaps outside of Westminster, that had been heavily adorned with Pride flags, and that reminded me of nothing so much as the Israeli flags I’d seen on many occasions in the old city of Jerusalem. When so many flags need to be displayed, my thought in that ancient walled citadel had been, it’s safe to say that this has less to do with pride —not only in the exalted sense of fierté, but even in the venal one of orgueil— than with an anxiety for the preservation of a regime the fragility of which its enforcers feel all too heavily.

Anyhow, Deneen/Vermeule added a comment in the form of a rhetorical question, something like: “The neutral public sphere?” And indeed I found I was unable not to feel the rhetorical force of it. We really were an awful long way here from anything remotely like what had been envisioned in the long tradition extending from Erasmus through Habermas as the very basis, the inviolable safe space, of secular modernity: the idea that our streets and our public squares are to remain neutral as between substantive conceptions of the good. What had emerged instead, perversely, was a conception of liberalism as the enforcement of a particular set of ultimate commitments, and even the coerced affirmation from citizens qua citizens of these commitments. Now it may have been simply inevitable that things should have come to a head in this way, under external pressure from so many different species of illiberalism. But to deny that in coming to this extreme point liberalism had, willingly or under compulsion, warped or abandoned a number of its bedrock principles, came to seem to me simply dishonest.

Anyhow my purpose here is not at all to establish my clean credentials in the eyes of the current regime and its ongoing process of dewokeification. My purpose rather is to establish just how deep my opposition is to this current regime — which, in case you haven’t noticed, has, to say the least, some ultimate commitments of its own.

There were a number of people I admired throughout the years of our previous regime, who seemed to see it for what it was and were unafraid to describe it in terms that sounded truthful to me. Call them curious bedfellows, or circumstantial allies, the fact is that around 2021 I often found myself nodding my head in affirmation of what I was reading from people you might broadly describe as members of the “dissident right”.

Some of these people, in 2026, remain lucid and courageous (Andrew Sullivan comes to mind) — but alas, not the great majority of them. I had, naively, taken them all to be dissident by nature, and it was assuredly more their dissidence than their right-wing self-identification that I admired. Many turn out simply to have been circumstantial dissidents. It was not at all that their conservatism, if you can even call it that, was shaped by a sentiment akin to the great Chateaubriand’s, who once remarked that “the pride of victory is unbearable to me”. It was rather that they simply didn’t like being out of power, or, rather, they didn’t like it that those people were out of power with whom they had allowed their own identities, in their weakness and their lack of dignity, to become wrapped up.

In the end this all could come down, at least in part, to a question of temperament. I cannot imagine ever getting what I had wanted, and then declaring “I’ve got what I wanted!” and settling down with it, as a number of the anti-woke former dissidents seem to have got in November 2024 with their ultimate owning of the libs. Whenever I get what I want, I immediately start to see what had been wrong with it all along, and so start wanting something else. In part I’m just harder to please than all the current regime propagandists with whom I had some real affinity five years ago.

But even if there were no question of the role of temperament —which I think Chateaubriand rightly recognizes to be mostly fixed in each of us—, it would be plain to anyone with any sense and any honesty that this regime stinks, that it has latched onto the very worst latent impulses in the American legacy and positioned them at the center of a spurious narrative in which they are the expression of the American spirit itself.

So to all of you with whom I have once had common cause, I say: please, you are not my enemy. This current regime is our enemy, the enemy of anyone who loves their freedom — of conscience, of assembly, of expression (and evidently now of bearing arms too). None of this has anything to do with whatever your particular “political opinions”, such as might be solicited on a questionnaire, happen to be. I don’t care about your political opinions. I don’t even care about my political opinions, as I believe we’ve established already.

But I do care about honesty, and so feel the need to implore you to be honest with yourselves. Trust your own eyes and your own conscience over regime propaganda. When Florida Congressman Randy Fine claims that Alex Pretti was an “insurrectionist”, and describes his murder in veterinary terms as a matter of being “put down”, this is obviously nothing more than craven lying from a pathetic propagandist and stooge. (“Where do they find these junglies?!” a dear Pakistani friend once said, with aristocratic disdain, as we watched Jesse Helms trying to form a sentence on television — a memory that comes back to me now every time I see Fine’s thick brutish self-contented mug on the internet.) But your honor and your self-respect require that you not volunteer your services as a regime propagandist yourself. You are better than that. Even Randy Fine is better than that, though we may have little ground for hoping that he will ever become aware of this. You are better than that simply in virtue of your humanity, and of the God-given faculty of reason that comes with it.

This regime is my enemy, but it is also the closest thing I have to an ally. The story of this age, for me, is not the deprivations of the right, anyone who can read a book will know that this is what they have always been, but the degradation of the left. I don't think Trump has won as much as the left has lost. And as long as every Pretti is matched by a Kirk I don't think that will change.

My life and career are still being governed by the rules put down in 2020 and it seems my choices are to remain quiet and embolden people who openly hate me, or to empower people who hate others even more.

I don't think a lot of well meaning people established in their careers realize how bad things have become, and how much worse they are still likely to get. I think this is just the start. https://www.compactmag.com/article/the-lost-generation/

It would be instructive for readers to learn who, in your estimation, have betrayed your ideal of independent thought in order to become regime propagandists. Providing context—naming names—would allow the reader to determine whether your implicit claim to represent the ideal—even as imperfect striving—is closer to fierté or orgueil.