“The earth has bubbles as the water has.”

—Banquo, Macbeth

1.

Just three centuries after his Prophet’s message began to radiate out of Arabia, ’Aḥmad ‘ibn-’al-ʿAbbās ’ibn Rāšid ’ibn Ḥammād ’ibn Faḍlān arrived on the banks of the Volga, and saw there the burial of a chieftain of the Rusiyyah. When such a man dies, the traveller reported, his kin go among the slaves and ask them who will die along with him. And a slave girl speaks up, saying: I shall.

And then the girl is treated almost as a chieftess, and the other slave girls attend to her, and her feet are washed with care. Meanwhile the chieftain’s body is laid out, and new garments for his burial are sewn. This takes several days, and every day the slave girl gets drunk, or is made to get drunk, and sings either happily or mournfully. The chieftain’s ship is drawn up on the bank of the river, and a wizened crone who has been dubbed the “Angel of Death” lays out a bed on top of it, and covers it in Byzantine silk. His men dress him in his fine new caftan with gold buttons, and place him on the couch upon the ship. He is surrounded by fruits, beer, onions, meat; his beloved dog, cut in two; his two finest horses, likewise bisected; two cows, in several pieces; a cock and a hen, headless but otherwise whole. The girl is raped by several men in turns, until she announces: He calls me.

She removes her bracelets and hands them to the Angel of Death. She removes her anklets and hands them to her loving attendants, from whose ranks she emerged just days before. She drinks from a cup of alcohol and she sings a secret song. The Angel of Death then grabs her by the hair and pulls her into the pavilion that has been constructed over the chieftain’s couch. The men pound on their shields to drown out her screams for those who are attending from the riverbank. The Angel of Death stabs her repeatedly with a dagger between the ribs, and the men pull at a rope around her neck, until she dies, and joins her chieftain, and the whole great hecatomb is buried together with the ship under a tumulus by the side of the Volga.

The silk of Byzantium, a dainty ornament mentioned in passing by ’ibn Faḍlān, speaks volumes. How did it get there? The Arab traveller wishes to describe for us a world upside-down, where none of the ordinary laws of civilization hold, where men do not even wash themselves after defecating, and sacrifice girls and animals as if these creatures were not dear. But they do so from their position within a well integrated network of trade, connected by the river highways that brought the Baltic together with the Black Sea, and Vikings to the court of the Greek emperor at Constantinople. ’Ibn Faḍlān was himself a traveller on these highways, and a participant and beneficiary of the commerce that thrived on them. He seems to have stood silent in witness of butchery, and sought to redeem what he had seen through the edification of others, writing about it in the vein of curiosity, marvelling at the extraordinary variety and inventiveness of human cruelty.

This is how Russia entered into the consciousness of the world (when the world spoke Arabic): a man passing through stops to gawk at the unspeakable violence he witnesses there, and then transmutes his dumb passive silence into words, into text and into history.

2.

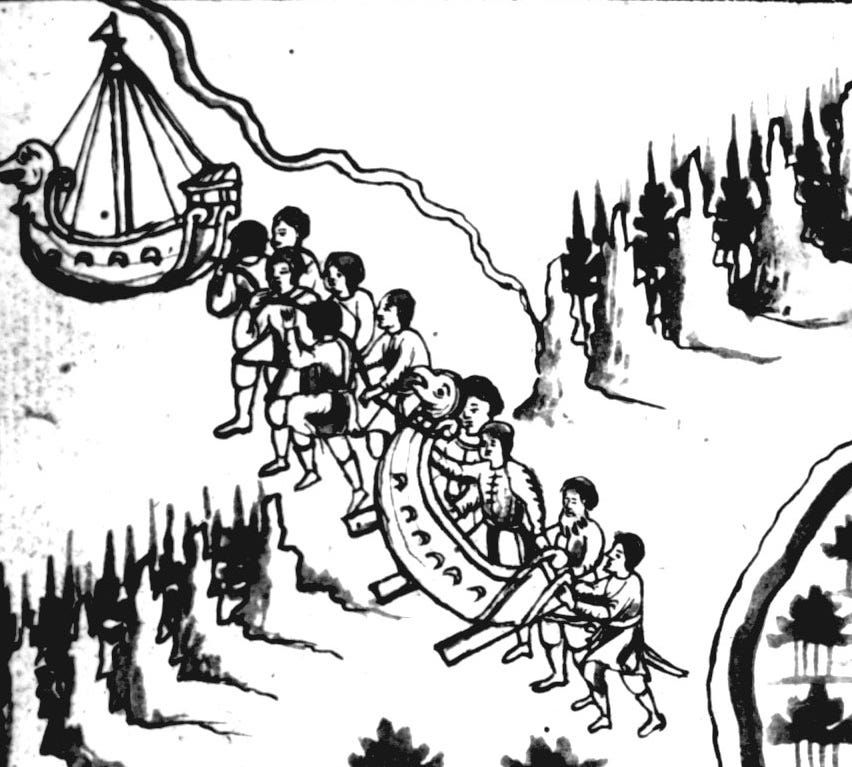

Ship burial is a recurring theme, both in history and in legend, reported not only by outsiders but in the Primary Chronicle itself. When Olga of Kiev’s husband was murdered in the Drevlian uprising, and one of the culprits, a certain Prince Mal, then sought to take her hand in turn, Olga accepted. She summoned Mal and his men “for a great honor”. Wary, they replied that they would not come on horses, nor in carts, but wished to be carried in by boat. And the Kievans said: “Our princess longs after your prince,” and they carried them in by boat. The Chronicle tells us of how Prince Mal’s men sat, exalting with pride, on the cross benches of the boat, and of how, when the boat arrived at Olga’s court, the Kievans who carried them in cast them into the pit that she had caused to be dug the night before, boat and all. Olga peered in and said to them, “Is that honor good enough for you?” (приникъши ѡльга и рече имъ, добра ли вꙑ чєсть), and then “she commanded that they be buried alive. And they covered them.”

Later European travelers will relate that throughout the deserts of inner Asia the Chinese go about in sailing vessels modified to move across sand. At the western edge of the same broad region of the world, in Ulug Ulus, known also as the Golden Horde, one of the several khanates left over from the Mongol Empire, ships are likewise somehow land-conveyances, and here to go down with the ship is sometimes to go down into the ground. From Taklamakan to the Volga, and sometimes even to the Danube, it is hard not to think of the continent as a great telluride ocean. In the De Magnete of 1600 William Gilbert suspects the Eurasian land mass is so enormous as to warp the Earth’s geomagnetic field, pulling the magnetic pole of the planet towards its center, and confusing seafarers on all the liquid oceans of the world who are thus unable to get a proper reading from their compasses.

By the time of Olga’s revenge the good news of Cyril and Methodius has spread and taken root, and with it the alphabet adapted from the Greeks, and the saints and angels, and promise of eternal life. Worship of streams and stones, and fornicating in the meadows on the days and nights of high festival, are abandoned by the people in villages and on farms, finding eternal life more attractive. Where these satanic habits are not abandoned by choice, they are eradicated by force. But the forests are large, and as every tree and every rock is potentially an object of reverence for people still carrying inwardly a pagan disposition, the Christians could never produce enough icons to outnumber the idols of nature. Still, the monasteries multiplied, at Kiev, Novgorod and Vladimir, and Moscow after them.

Wherever there was a church, there were fortifications, and weapons, and fear. The Tatars were given an extra r in their name and called “Tartars” by Europeans and Byzantines, who could not help but envision them emerging from the depths of Tartaros. “Tartar” became a generic term, for any number of people of various faiths and language groups. As Muslims, as Turkicized Tengriists, or as Mongol worshippers of the Great Lama, whether writing from right to left or from top to bottom, or just not writing at all, the primary movement on the continental ocean was along the East-West axis, and on horseback. The Horde burned Moscow to the ground as it expanded like a lung from Mongolia toward Poland, then contracted. Three hundred years later Ivan the Terrible vanquished its descendant khanates at Kazan, Astrakhan, and Sibir. In all this ebb and flow the principal technological innovations occurred in the domain of war engines and apparatus of torture, though many were killed by tools and stratagems that did not need to wait for the era of smelting and metallurgy to be implemented. Men were ripped into four parts by the four horses to which each of their limbs were tied, and their executioners laid down bets on which horse would get the largest share, as if the animals were pulling at a wishbone. Men had boiling tar poured into their mouths, even as they were muttering their final prayers. Some are reported to have met their deaths in joyous ecstasy.

The descendants of the vanquished khans became Russian princes, tsareviches, lost their languages and their faiths. “Scratch a Russian, you’ll find a Tatar” (Поскреби русского, найдёшь татарина) is a line variously attributed to Napoleon, to Joseph de Maistre, to Madame de Staël. Whoever said it first, we know that Lenin would soon enjoy riffing on it (“Scratch a certain kind of communist, you’ll find an Imperial Russian chauvinist,” he said in 1919), and that it became a commonplace in the underground humor of samizdat joke-books in the Khrushchev era. There is no such thing as inherited national character, of course. The line in question conforms to the very definition of ethnic prejudice — the presumption that a person is constrained in who they might become in view of who their ancestors are. Yet the long historical process of Russification of subjugated inner Asian peoples is a real one, and one that has fired not only the imaginations of haughty French intellectuals —none in truth any more perceptive than Voltaire, who mocked the Poles for having “too many consonants” and “not enough vowels”—, but the self-imagining of Russians too. Vladimir Nabokov enjoyed recalling that he was descended from a Siberian family, a remnant of the Chagatai Khanate, given a noble title in the hope of keeping it docile. He thought this made him seem a bit dangerous, in a way that even Lolita could not.

3.

St. Petersburg was supposed to mark a clean break from the bloody legacy of the Russian Empire’s continental struggles. The Gulf of Finland opened out to the Baltic, to the former Hanseatic cities, to Holland. In Arab chronicles medieval Rus’ first greets the world on incandescent river vessels buried beneath barbarian kurgans, and eight hundred years later Peter the Great sees the destiny of Russia as dependent upon the construction of ships fit for the open seas. It’s always ships. He travels to Amsterdam incognito and studies naval architecture. He is enthusiastic about the founding of a scientific academy in his new city, but his advisors too often find him unwilling to hear any account of the structure and order of the sciences that does not place the practical science of ship-building at its foundation. And the measure of Peter’s love of ships is equal only to his corresponding hatred of beards, at least on the faces of the men in his own city. Did he really travel incognito there as well, only to accost unexpecting Petersburgers and to tear the hair off their chins with his bare hands? It is far more likely that he only offered to shave his friends’ beards for them, which is perhaps nice, if a bit judgmental. Either way he was inverting the legacy of Ivan, who held clean-shavenness a sin. This was the Petrine Enlightenment: force and coercion, an exchange of symbols, and the opening up of a port facing West.

Aristotle said that in Greece or in Persia, fire burns the same, and Peter understood why this banal truth mattered. In Russia, too, fire burns the same, and if the powers of fire and the other elements of nature are ever going to be harnessed to make Russia itself powerful, this can only happen by recognizing that, always and everywhere, fire burns the same. Fire burns the same for one nation as it does for its enemy. And because fire burns the same, so too does liquid fire, or what is sometimes called Greek fire and is said to be mixture of naphtha and quicklime and other secret ingredients — so too does it burn the boats of the Turks, when sprayed by the Greeks, as it burns the boats of the Greeks, when sprayed by the Turks. And when someday there is an incendiary projectile, some missile or bombus, with the power to raze entire cities to the ground, as if they had never existed at all, you may be sure that it will burn the same.

A man they called Dembai had been lurking around St. Petersburg as if in a trance. He slept sitting upright, and some say they had even seen him standing on the shore of Vasilyevsky Island, facing Finland, fast asleep. He came from Nagasaki, was traded over to the Russians after he wrecked off the shores of Kamchatka and the Itelmen took him hostage. Peter hoped for him to teach the Orientalists at the St. Petersburg Academy something about Japan, and to prepare them for an eventual voyage there, to open up for Russian trade the country that had for so long been open only to the Dutch. But Dembai seems to have been a fairly simple seaman, and did not have much to say.

He was however able to report a most curious circumstance of his home country, that since the Jesuits were expelled and the country was closed off to foreign influence, they continued to hold open a single exception: a single dock in a single port of the whole country, which happened to be located in his home city. This dock hosted an inspection bureau, where agents of the emperor reviewed, and cautiously admitted, books of the the Redheads, as they called them, which is to say of the Dutch, who stand in for all of the Europeans. In this way not the smallest quantum of foreign learning creeps into that island nation without approval, and when it does make it past the inspectors and into an approved Japanese translation, as in Morishima Chūryō’s 1787 compendium, Red-Hair Chit-Chat, it is so far removed from the circumstances of its origins as to appear as if dropped straight from heaven: the simple truth about the working of nature, and how to make good use of it.

Russia was not an island, and could not control the importation of books from a single inspection bureau on a single dock. In the centuries prior to Peter’s opening up of Russia, a typical inventory of a library’s books might include the Paterikon, and the Chronicles, and some translations from the Greek of animal fables suitable for moral instruction. In 1698 Christiaan Huygens’s Cosmotheoros was translated into Russian. At first it was taken by many to be another contribution to the large and familiar corpus of Byzantine-derived angelological writings, and the author’s arguments for the existence of extraterrestrials were read as yet another meditation on the nature and divinity of the celestial intelligences, the hierarchies of angels and archangels. Around the same time Jacob Bruce, a Muscovite of Scottish descent, who had read Francis Bacon and Robert Boyle and wished to conduct his own chemical experiments in a makeshift lab in the Sukharev Tower, was rumored by the locals to be practicing black magic: his copies of the Philosophical Transactions were said to be grimoires, and he was said to fly around in the sky over Moscow at night, using his telescope in place of a broom.

4.

The Tobol flows peaceably northwards, without cataracts or shallows. It is strengthened by the confluence of the Ubagan, and at the town of Tobolsk joins with the great Irtysh, and loses its name. Yermak Timofeyevich subdued these parts with the band of Cossacks whose thirst for battle he had whipped up on the promise that the inhabitants there were among the only people in the world more vicious than they themselves. They eat horses, it was said. They eat raw horse meat. They sacrifice their own horses and eat them raw. They drink the blood of their own horses while still alive. They mix the blood into fermented mare’s milk, or if none are nursing they use horse piss instead. They have no speech, but only neigh like horses. (The use of urine in common recipes seems to have been an innovation of the Vikings — thus the foul-tasting salmiak licorice so beloved in Nordic countries derives its name from sal ammoniacum, which by the time of the Viking expansion Arab alchemists had already isolated from their own piss. This last dietary custom of the Tartars evoked by Yermak, I mean, is in fact widespread.)

And so the Cossacks went to war, on horseback, against the horse-men. At the confluence of the Tobol and the Irtysh they found a few Tartars doing what they could to mount their resistance and maintain the Khanate of Sibir, whose leader Kuchum, unworthy descendant of Genghis Khan, was miles away at the fortress of Qashliq, and was by now in no position to convey military orders across his crumbling dominion. So the Tartars were defeated swiftly, to the disappointment of Yermak’s men, without displaying any of the ferocity, or giving off even a hint of the infernal stench, for which they were legendary, and which Yermak had promised them.

Other than the defeated Tartars the only inhabitants to be found in the region of Tobolsk were the Ostyaks, today known as the Khanty-Mansi, who knew nothing of horses, but fished, hunted, and traded pelts. In the world they knew, and in which they would have preferred to remain, the greatest ferocity on display came from the giant hawks that swooped down to pick not only fish from the Irtysh, but waterfowl too, and could even nab a poor duck that had retreated under the water to hide from this menace, leaving only its beak as a sort of breathing straw above the water’s surface. At the time of the Great Kamchatka Expedition (1731-1741), the Ostyaks had only the faintest awareness of the place called Saint Petersburg, which was held by the Russians to dominate even in this remote place like the soul in a body. One Ostyak elder is reported to have told a Russian merchant that, if Saint Petersburg is the soul of the body of the Russian Empire, then the Ostyaks are the hairs of the leg or perhaps the toenails: in any case some part that cannot be flexed at will, that cannot be quickened into motion by any decision taken, and that could just as easily be sliced off from the body with no pain at all on either side of the cut.

Yermak’s conquest of Tobolsk in 1582 was an early peristalsis in the same organic motion that would bring Russia to the Pacific coast of Asia within the next half century. In Eurasia there are not so many ways to get a mare usque ad marem. You might do what the Western Europeans had long done, and set out in a ship to round the Cape of Africa, sailing from there acrosss the Indian Ocean and through the Molucca Strait. Or you might travel the Silk Road to the South, through Bukhara, Samarkand, and around the edge of the Taklamakan Desert all the way to Peking. But both of these routes were well trodden, if you may trod the ocean, and indeed it was said that the water must show by now a permanent groove in its surface for all the traffic that had gone from West to East and back again.

Passage across the Northern Ocean was impossible, for it is frozen solid too much of the year. In the century before the Petrine Enlightenment, Semyon Dezhnyov, an illiterate Pomor, is said to have set out from the mouth of the Kolyma River and entered into the Pacific and probably arrived at an Alaskan island. But he left from a point on the Northern coast of the empire nearly nine-tenths of the journey Eastward from Arkhangelsk. Dezhnyov was one of many Russians who since the Middle Ages had moved across the Arctic and gradually become Indigenized. His world was one of reindeer hides, spears, seal blubber, not one in which it would make sense to report back to an academy of a previously unknown geographical feature — which is why we speak of the Bering Strait and not of the Strait of Dezhnyov.

If you are setting out from Tver, north of Moscow, the Volga can carry you East as far as Kazan, but from there it turns to the South, towards Astrakhan and the Caspian Sea, which would set you on the Southern route to China carved out already in antiquity. The Ob, while it has a slight tilt from Northwest to Southeast, is useless to carry you in the desired direction, unless you are equipped with a team of rowers, or with reliable sails and are prepared to tack for hours and days on end, as it flows into the Northern Ocean. The Yenisei, from its sources near the homeland of the Mongols, flows due North into the same. The Easternmost of the great Siberian rivers, the Lena, flows to the Northwest from Lake Baikal to Yakutsk, before turning to the Northeast and issuing likewise in the Northern Ocean, after having flowed past strange geographical features for which no true name can be found in translation: alaases, pingos.

Otherwise, there are horses, or, for long stretches in the snow, if you are so inclined and so outfitted, there are dogs. Horses have this advantage, that they may be hitched to either wagons or sleds, and the men and supplies they carry may thus be either rolled or dragged. Nor must a man stay with the same set of animals for his entire voyage. The Mongols had left across Siberia what is known as the “Yam”, a Siberian Pony Express, a network of carefully spaced posts to which messengers and travelers rode, and there received fresh horses in exchange for their exhausted ones, which would feed and rest until they were fresh in turn, and ready to be sent further along when a new set of travellers arrived. The Russians inherited the Yam from the Mongols, and the horses scarcely perceived the transfer of power between them.

Horses cannot travel as fast as arrows, let alone as fast as the charge that runs through water when lightning strikes it, or the invisible waves that some held to emanate from crystals, or yet any other secret signal that flies through the ether or the earth unperceived — yet voyagers were often heard to speak of the mysterious unifying power of the Yam, how through it several horses become as one horse, the motion of their animal bodies across the land comes to appear to them the same as the motion of the animal spirits and animal blood from their hearts and down into their legs and back again. Each horse becomes as a single image in a sequential representation, as that of Trajan’s Column in Rome, or the stations of the cross that line the inner walls of a church, where you know that the Christ who falls for the first time is the very same as the Christ who falls for the second time: so too it appeared to travellers that the horse that stumbles into Tomsk on the point of collapse is the same as the one that stumbles into Yeniseysk. In this respect through the Yam each horse both loses its individuality through absorption into its genus, where every member of the kind is now identical and interchangeable, and, at the same time, in this dissolution each horse becomes more than any horse ever could be by itself, a Pegasus spanning continents, a channel and epitome of the power and virtue of every horse that ever was or will be.

5.

To the preexisting Mongol horse-posts the Russians added distillation — and Siberia was settled. By 1700 virtually no village or ostrog between Yekaterinburg and Okhotsk was small enough to lack a pot-still or an alembic for the etherealization of grains into spirits, which, the alchemists proposed philosophically and the Siberian drinkers understood implicitly, is only the finest essence of the coarse fruits of the earth, drawn out of them ingeniously, yet without the creation of anything properly new. Spirits are spirituous, which is not something wholly distinct from the spiritual, like the pneumatic bodies that are said to sustain the lives of the angels, so different from the sluggish and torpid material bodies that keep us anchored down to the earth.

The Mongolic Buryats understood this too, and began mixing Branntwein into their mare’s milk, a drink they found especially suited to the feasts of the convocation of the gods, where the priest drank, and danced, and growled like a snow leopard until he had, so it was said, transported his spirit to the world where the gods dwell. Now as spirituous as they, the priest convinced them to come back with him to the yurt in which his trance had begun and to attend at the slaughtering of a goat in their honor. The young man who did the slaughtering, too, was drunk on Branntwein. He made a small incision in the animal’s belly and reached his arm in up to the shoulder, extending his hand all the way to the neck, then grabbed at the main artery and pulled. When the goat’s meat was cooked over the fire, there were spirits there as well, now manifested as smoke, which, far more than distilled grains, was thought pleasing to the gods.

Spirits were abundant, and consequently very often of little value for trade. Bread and tobacco, by contrast, could put shoes on horses, pelts on a man’s back, could be exchanged for Chinese rarities brought from the border trading post at Kyakhta: porcelain, tea, rice, ginger, or the inner parts of the poppy flower which, when smoked, transport you further than any Buryat priest has ever gone to meet his gods. Tobacco was particularly prized by the Yakuts, ever happy to receive it in exchange for transit on a dog sled from Baikal to Yakutsk, a three-week voyage if all went well. The dogs were attached eight to a sled, and two men could ride behind, with another sled carrying supplies. The dogs seemed tortured throughout the day’s journey, and were punished harshly by their Yakut masters every time a distant scent, perhaps some sign of life piercing up through the snow, reached their noses and caused them to go a bit astray. Yet each morning at dawn the dogs were up again running in circles, signalling to the men their eagerness for another day of the same.

Although the voyage takes three weeks, Irkutsk and Yakutsk are conceived as neigboring towns. Distance is reckoned differently here. Lake Baikal itself, which one ordinarily crosses toward the Southeast from Irkutsk in order then to head Northeast toward Yakutsk, defies any European sense of scale. The Buryats there do not like to hear it called a lake. They say that Baikal itself does not like to be called a lake, and if any traveller should characterize it as such when he sets out to cross it, he may expect to find himself lost in a maelstrom before he reaches the other side. The seals of Baikal, too, are said to applaud such tragic events, by striking their flippers together excitedly when they catch sight of a ship in peril from the rocky shores. But what lake properly so called is home to seals? These more than anything stand as testament to the paradox in inner Asia of the proximity of distant places. We can only infer that the Baikal seals arrived there from the Northern Ocean, no matter that they must have travelled 1500 versts to the South to reach their new home.

6.

There were in fact two institutions inherited from the Mongols when the Russians took Siberia: the Yam, to which we have already been introduced, and the Yasak, which is to say the payment of tribute by the local peoples to the representatives of the Tsar. It is difficult to conceive what might count as rule at all, where there is no tribute or taxation, no extraction of wealth by the sovereign’s men in exchange, purportedly, for protection. And in the Yasak there is not only extraction and protection, an exchange in which one of the parties received not goods but only abstract promises. There is also, at least in principle, a proper recompense of the Siberians for their sables and other pelts, in the form of flints, knives, red cloth and most of all tobacco. And when the Siberians find the exchange is not in their favor, they hurl the pelts along with curses, they kick them through the air or tie them to the necks of their dogs. And when the Russians grow impatient with these protests they retaliate with mass executions, hostage-taking, rapes. Their demands increase, driving the stoats and the foxes to near extinction, so that the Yakuts and the Yukaghirs and the Tungus often have no choice but to steal the few remaining pelts from their neighbors, or to buy pelts at exorbitant prices in order to pass them to the Russians in exchange for their mere lives.

For a long time there was a sort of spiritual Yasak, too, which began where the Yasak of goods left off, when the shamaness takes the tobacco her husband has received for his reindeer hides, and lights it up, and the old crones she has invited to join her begin to bang on their drums, which jingle with brass rings attached to them, and she performs a series of motions something like a dance, though not quite, and chants in a language only she understands. She holds a devil carved into wood, a figure of a man’s head dressed with cloth for hair, and she entreats it to grant her access to the realm above, or to the realm below, from which the wooden devil comes. And when her incantation is over she invites the Russian traders assembled in her home to ask questions, which she answers in her own language, in a manner so obscure and general as to convince no skeptic.

The Russians sit on benches covered with the hides of wolves and bears, which also serve as the sleeping quarters of the family. An iron kettle hangs over the fire, and perpetually simmers some sort of stew. The home is an izba, built up out of large beams of wood separated by layers of moss. A hole has been cut for a window, but no pane of glass is placed in it. Instead a block of ice has been shaped to fit the hole and polished to a vitreous transparency to let the light through, even as it distorts the figures of outside objects seen from within. It is April now, and the day trades off with the night in equal exchange, and the light of the sun filters in through the day, and the light of the fire trickles out at night, and the men come in with meat that is then cooked up in the kettle and eaten, and digested, and perhaps the woman under influence of smoke and charms really is informed of all past and future events, or only feels as though she is, or is only pretending to be.

It is largely beside the point to wonder whether a shaman is a con-artist or not — the very distinction between a performance and “the real thing” already presupposes a “culture of fact” in which the two parties to a moment of intercultural contact such as the one I have just described do not share equally. A culture of fact is one in which the exhaustion of goods is also the limit of exchange. This is clear already in 1556, when the English merchant Richard Johnson attends a Samoyed (Nenets) ceremony, thousands of versts to the Northwest of the Buryat scene just related. As reported by the great Richard Hakluyt in his multivolume work, The Principall Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, at the ceremony an elder removes his shirt, wearing now only a pair of deerskin pants “with the haire on, which came vp to his buttocks”. The elder’s associates proceed to take a deer-hide rope and to fasten it around his neck and under his left arm, the ends of which the two men then hold on opposite sides of him. A kettle of hot water is set in front of him, and a shroud is lifted to conceal the whole scene from Johnson and a handful of other spectators. Next the two men walk out in opposite directions from behind the shroud, pulling on the deer-hide cord.

What Johnson reports at this point deserves to be quoted in full (I quoted this passage in a very early Substack, and you may be sure that I will do so again in the future):

I hearde a thing fall into the kettle of water which was before him in the tent. Thereupon I asked them that sate by me what it was that fell into the water that stoode before him. And they answered me, that it was his head, his shoulder and left arme, which the line had cut off.

Johnson writes that at this point he attempted to raise up and peer behind the shroud, but that the Samoyed men sitting next to him blocked him from doing so, insisting that “if they should see him with their bodily eyes, they shoulde liue no longer.” And it’s at this point that things get really strange:

Then they beganne to hallow with these wordes, Oghaoo, Oghaoo, Oghaoo, many times together. And as they were thus singing and out calling, I sawe a thing like a finger of a man two times together thrust through the gowne from the Priest. I asked them that sate next to me what it was that I sawe, and they saide, not his finger; for he was yet dead: and that which I saw appeare through the gowne was a beast, but what beast they knew not nor would not tell.

Johnson is an English merchant traveling at a time before the Scientific Revolution. But he is already attuned to the values of facticity and “probability” —in the sense of having a reliable character, one worthy of “probation” or “approbation”— that will be made gradually more explicit in the following century. It is not hard to sense his impatience with this spectacle. He wants to get on with things. He’s there to make deals.

The history of the modern world has witnessed a gradual elimination of spiritual exchange in favor of exchange of goods. Goods become the highest —indeed the only— good known to men. Though it may once have contained the secret of existence, Oghaoo now sounds to us like a nonsense word.

7.

Admiral Vitus Bering knew enough, when he and his crew arrived at Yakutsk in the midsummer of 1735, to know that such a town as this could only have been built with the arrival of the Russians in the previous century. The Russians built against the elements; they were not only there to conquer Yakuts, but nature too.

Bering had arrived along with his wife Anna and a scattering of children. They came by barge up the Lena from Irkutsk, with a complete set of porcelain tableware purchased at Kyakhta from the Chinese, and a clavichord carried mostly overland from Moscow before its final river journey to its destination, deviating further from its fine tuning with each stone in the road, with each motion of gruff laborers who knew nothing of the transcendent beauty of Buxtehude, with each new day of unfathomable cold, with each new day of its life in Asia.

The clavichord arrived at Yakutsk sounding like its harmonies were borrowed from the spheres of Hell. Anna was upset. The only other proper musician in the town was a trumpeter. The sheet music she brought along would have to be rescored before there were to be any dances. She could retune the clavichord herself, but would simply have to work around its two broken strings. It was not her idea to come to Yakutsk. Her sister Eufemia had married an English officer of high rank. The only way Vitus could attain any sort of rank at all was by serving, as a Dane, in the Russian Admiralty. This was not so difficult to endure when Russia’s military efforts were concentrated around the Baltic Sea, but now here she was, in the coldest place on earth, surrounded by heathens and by Russians who, in their desire to flee from their pasts at the farthest-flung extremities of the empire, had characters generally lower than those of heathens, or that would soon become so through the unrelenting debasements of their new surroundings.

Once the clavichord was tuned and the porcelains were unpacked, the Bering residence quickly became the center of Yakutsk life, the place where disputes were resolved, plans were made, and, against the elements and all likelihood, a certain kind of Hanseatic comfort was simulated. There were concerts where the officers and their ladies waltzed. A few had come with their wives, others picked up Cossack women along the way. Yakuts were pressed into servant roles, wearing uniforms and carrying trays, performing Sisyphean primps for their masters and mistresses the precise symbolism of which surely escaped them, even as every action, of theirs or of the Russians or of those of other European nations, reinforced the inescapable and obvious fact of hierarchy.

Even before Bering died of scurvy on an Alaskan island in 1741, his wife had determined to pack everything back up and return to Europe. The records of the Imperial Post from this period tell quite a story of the Westward flow of goods across the earthen ocean. We read of two ends of nankeen (soft red); three Yakut sables, with paws and tails; one Chinese doll, made of brass, with springs; one piece of lynx-belly fur (small); eighteen pounds of khan-silver, in bars; a pistol, handle engraved with mammoth-ivory plating; a polecat, stuffed with hay; one Japanese lacquered box, containing a natural specimen of an unidentified sort; silver goblets (three); shirts of Chinese taffeta (seventeen); a crystal saltcellar; a pair of small German pistols; a brass-mounted Turkish shotgun; a steering quadrant; a walrus-tusk handle; a coat of snow leopard; a bundle of azure nankeen; an unnumbered quantity of Yakut vole pelts; a brass tea caddy; a mammoth-tusk comb; a sanaiak of lynx; an hourglass for measuring quarter-hours; a deck of cards; a satchel of cubeb; six arshins of red fabric; an enameled tea-kettle with scenes commemorating the Treaty of Nerchinsk (depicting a Russian merchant like a bear holding out its own pelt to a Chinese trader extending back a little box of tea, the former’s Polish Jesuit translator discoursing amiably, in what could only be Latin, with the latter’s Italian Jesuit translator); a brass sextant; a reindeer merkin; forty-two Arctic fox paws bent into the shape of hooks and intended for use as napkin holders.

We may picture the widow Anna Bering back in Vyborg, with table settings most unlike anything her sister ever managed.

8.

When my father made a brief visit to Checkpoint Charlie in 1986, he came back with a report of the Soviet soldiers he saw stationed there. They had enormous machine guns, he said, and “Mongolian” faces. He said they “scared the bejeebers” out of him. My father, too, was expressing a prejudice, though there’s something satisfying for me now about thinking of him as having “bejeebers” at all. Your bejeebers are what get summoned up inside you, perhaps, when you hear the words Oghaoo, Oghaoo, or when you imagine you hear them.

Some of my contacts in Yakutsk have gone incommunicado these past few months. I used to get from them scans of Olonkho texts held in the library of the Northeastern Federal University, but since Putin’s mass mobilization in early September, it’s hard to say where they have gone. For most of the Russian Empire (or Federation — whatever), the war in Ukraine really only began at the moment of this mobilization. This is when the “Саха Cирэ” Информационнай Биэрии, the daily Sakha-language newscast that I watch regularly on YouTube, switched abruptly from dull reports of pensioners growing unusually large cucumbers in their greenhouses, to stern announcements from regime officials outlining who exactly must report for duty and where, which categories of men are exempt, how much money families will receive in case of death, and so on.

Though everything looks very orderly on the official news channels, I learn from unofficial reports that the round-up of eligible men is chaotic and terrifying. Everyone understands, moreover, that the relatively greater frenzy of the round-ups in the Asian republics and oblasts and okrugs is a matter of policy. It is not only that the regime has an interest in preserving an appearance of normalcy in Moscow and St. Petersburg, but also, somewhat as my father’s bejeebers intuited, that Putin wishes to conjure in the heart of the European Union the same terror of Tartaros that pervades the earliest Western European travel reports from “Muscovy and Tartary”, and that is on display in the French and English medical texts telling of the condition known as plica polonica or “Polish plait”, which affects not Poles but the Tartar horsemen who serve in the cavalry of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, who grow a single dreadlock from the top of their heads that becomes so matted and dense that the blood of the body itself begins to circulate through it, so that it cannot be amputated without killing them — it’s hard to say exactly where the boundary is, but there is a line somewhere to the East, beyond which things get weird. Putin has recently been heard conjuring up old anti-Westernizing tropes, reflecting that Americans are wrong to look at the Chinese and think, “They’re different from us,” while at the same time looking at the Russians and thinking, “They’re the same as us”. The Asian minorities of his empire help him to make this point. Americans, along with the other inhabitants of the Atlantic world, are so preoccupied with “race” that they can’t imagine carving the world up any other way. Putin sees things differently, and knows how to play on Western fears — he is the pirate captain of a multiethnic band, sailing the telluride seas of Eurasia.

The rather modest Sakha film industry features several retellings, all of which I have watched by now, of the glorious role Yakut soldiers played in the “Great War for the Fatherland” against the Nazis. A small number of young Yakut men today would like to experience some of that glory for themselves, and are eager to be called up. They are proud to be part of an empire. Yakutia is too distant and cold and obscure for most of the world to know it exists, but Putin can at least make the whole world pay attention to Russia. A much smaller number of these men, in turn, would like to experience some of the ignominy that always accompanies war: rape, theft, the slaughter of innocents.

We almost never ask ourselves why Russia is so big — big like the Spanish empire before Bolivar, like the French empire until its abandonment of North America in the eighteenth century, indeed like the United States with its own globe-spanning empire that it still somehow manages to pass off as a regular nation-state. The French, Spanish, British, Dutch, and Portuguese empires had, and to some extent still have, the most familiar modern imperial arrangement, whereby the bulk of the empire lies across an ocean from the metropole. Turkey, Russia, and for a while Germany too, had no ocean to cross in their own territorial expansions, and curiously this circumstance has made it easy for at least one of these latter empires to “hide” itself with surprising success. The reason Russia is so big is because most of it is not Russia.

9.

German sources from the period of the Great Kamchatka Expedition tell us that the Ostyaks had a peculiar belief about the origins of woolly mammoth tusks. They said these come from a currently living species of animal, which dwells underground and uses its singular ivory protuberance to bore the tunnels in which it lives and moves. For reasons the Ostyaks do not explain, when the beasts die their tusks float up to the surface of the earth, as they would in water. When we push further east towards Yakutia, these subterranean creatures shade gradually into the abaasy, the demons of the Lower World. In a seafaring empire it is the unseen creatures of the depths known only from their moulted parts or their exuded ambergris, rather than the extinct terrestrial megafauna, that feed the legends that bespeak the terror and confusion of life on this hostile planet: the grampus; or the narwhal, whose tusk may in fact come from a unicorn; or the manatee, who might be a siren and who will kill you if you give in to its seductions. As in any ocean, there is a whole world under the surface of Eurasia.

This is really brilliant, fascinating, hair-raising, and fun to listen to and read. Love the fluidity of genres melting between accounts of “voyages” and 1001 nights, between ethnography and geographic expedition, between horror and science... and one cannot miss the deep notes of love and concern for a wild, beautiful, multifaceted, raw yet human “ocean of earth” that asserts its indomitable independence, whatever history may throw at it. Keep writing like this!

Beautifully written! There seems to be much too little awareness in the West of Russia's weird hybrid "national" "identity" as a multiethnic country from way back. It's hard to figure out the implications in the current situation. It's been (morbidly) fascinating to watch Putin tout Russia as a kind of mulitcultural utopia at the vanguard of anticolonialism, while Russia's ethnic minorities seem to be bearing the brunt of recruitment. I follow some alternative Russian media like Meduza and have been reading different views on how popular this approach is likely to be, and with whom. I find myself wondering to what extent the recruitment of minorities is a conscious strategy to ensure a clash of ethnicities at the front, with Buryats and Chechens marching into Ukrainian cities. And then, when Ukrainians refer to the Russian soldiers as "orcs", in what way this response is also a racialized one.

A tragic irony is that Ukraine's "national" "identity" is also, a different way, multiethnic - Ukraine literally meaning a border area, where cultures meet, and with the mythos of the ragtag band of Cossacks, etc. The German historian Karl Schlögel has argued that this gives Ukraine the potential to serve as a bridge and develop a special kind of cosmopolitanism. Of course, that was before the war.

And now we have two bewilderingly complex "national" "identities" at war with each other, and in Berlin, where I live, the streets are full of refugees from the Donbass switching fluidly between Russian and Ukrainian. One can only hope that these complexities and ambiguities can survive and achieve some kind of peaceful coexistence. And for now, that everyone can get through the winter with a minimum of death and destruction. I hope your friends in Sakha are ok!