1. Readying the tub

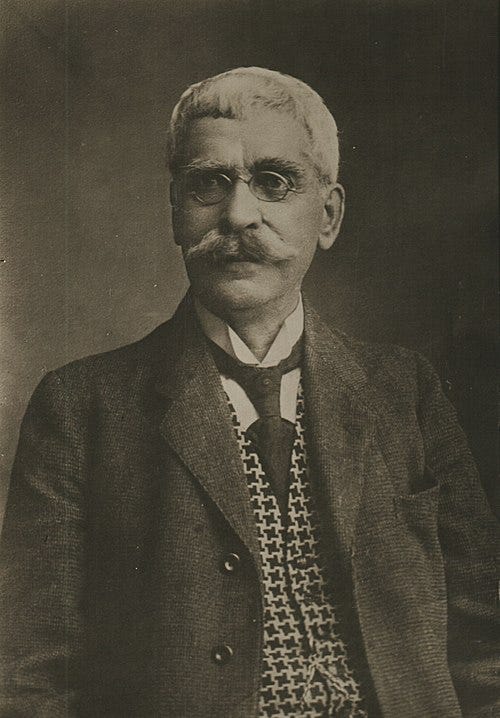

In Bulgaria, everyone knows Ivan Vazov (1850 –1921). The National Library in Sofia is named after him (Народна библиотека “Иван Вазов”), as is the National Theater (Народен театър “Иван Вазов”), along with countless parks, primary schools, streets, and squares. Statues of his likeness are scattered across the country, stern reminders of a man whose words shaped a nation.

Vazov is called the “patriarch of Bulgarian literature”, and his reputation bridges epochs: from the long twilight of Ottoman rule to the new dawn of post-liberation Bulgaria, when the country turned its gaze to Western and Central Europe. His writing provides an opportunity to think not just about this fascinating, ancient land, but about the construction of identity itself: about how we humans wrestle meaning and belonging from the sound and fury of history.

Bulgaria is a land of poets, and Vazov, though also a playwright and prolific prose writer, was most of all a poet. His fight (or at least his chosen subject) was freedom from the Ottomans. He was a comrade, at least ideologically, to more, shall we say, violent revolutionaries like Hristo Botev and Stefan Stambolov. His works rage against Turkish massacres and atrocities, and one of his most famous poems, the aptly titled “Аз съм Българче” (“I am Bulgarian”), helped usher in a new sense of Bulgarian identity: teaching children that they were born of a wondrous land [земя прекрасна], descended from a heroic people [юнашко племе]. He was, in short, the consummate 19th-century Balkan dude.

Yet, despite his power and importance, I must confess that I am not moved by his poetry. I did not grow up with his verses drilled into me, as Bulgarian schoolchildren did. My Bulgarian is good enough to follow the words but not his lyricism, his linguistic flourishes wasted on a mere novice. But Vazov is, however, quite interesting to me as a historical and philosophical figure, an entry point into the question of what it means to be Bulgarian, a way to inhabit what the philosopher Edmund Husserl called the Lebenswelt: the lived world before abstraction and conceptualization, the horizon of meaning that shapes our every action, thought, and perception.

Which is why I am not so much interested in Vazov’s verses as I am in what he did in the bathroom.

This may sound perverse, especially if, like me, you grew up in the United States, and even more so if you grew up in the austere climes of the Midwest: a world of bland casseroles (or, rather “hotdishes”), endless cheese, Christmas lights in November, Ford trucks (aka first on race day or, less flatteringly, fix or repair daily), and absolutely no communal nudity. At age eight, if you had asked me to name a poet, I would probably have said M.C. Hammer, having listened to Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ’Em until the tape wore out. And if anyone had asked me about Hammer’s bathing habits, I’d have screamed “stranger danger”!

I didn’t visit a public bath until my late twenties, when my Bulgarian girlfriend, now wife, took me to the Russian and Turkish Baths in New York’s East Village. Even then, it took years before I fully understood what was happening in such places, before I could grasp public bathing not just as washing in a room full of other folks, but as a horizon of action, a way of being. That understanding only materialized once I began living in Bulgaria.

So, it matters, symbolically and philosophically, that Vazov wrote a short essay called “В топлите вълни (Бански наблюдения) [In the Warm Waves (Bathing Observations)]”.

The following essay consists in a series of reflections in response to Vazov’s, as well as on a recent and very excellent series of essays on Bulgaria and baths in the online journal Семинар_БГ [Seminar_BG].

The bath is drawn. It’s time to get wet.

2. Baths, spirits, empires

The word banya is hard to translate. Americans prefer euphemism: we “use the bathroom”, “visit the restroom”, or “see a man about a horse”. These are nice(-ish) ways of avoiding the blunt and visceral facts of waste elimination (or, with Aristotle, the discharge of residues, perittōmata, which is, to me, a lovely way to think about waste: the leftover bits our bodies can’t use). But a Slavic banya has little in common with an American’s “bathroom”. It is not just a place of hygiene, but a liminal zone, that is, a threshold, a transitional place: a place for meeting, for ritual, for business, for gossip, sometimes even for encountering spirits or performing magic.

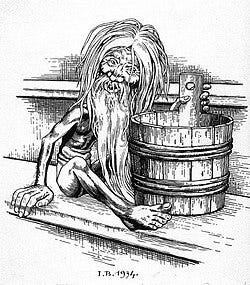

W. F. Ryan’s The Bathhouse at Midnight: An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia (1999) makes this clear in its examination of Russian folk culture. Here we find that bathhouse was a marginal structure, often built at the edge of the village, and spiritually liminal: a place between good and evil, life and death. The banya was said to house the Баник [Bannik], a fickle little spirit: a man with a huge head, wild hair, and a beard that could cover his entire body. These angry little dudes were frightening, all sharp teeth and claws, but could be placated with offerings of soap, water, or fir branches. To keep them happy, people left them their own corner of the bathhouse. A soft touch from one foretold good luck; claws meant the opposite (as claws usually do). Icons and crosses were forbidden inside, lest they offend the Bannik. Anger one, and they might harm children, suffocate bathers, or burn the bathhouse down.

What Ryan shows us is that the bathhouse was never just about washing. It was a threshold space: where cosmology and daily practice met, where danger and rebirth intertwined. To step into the steam was to risk transformation, to enter a world where impurity could be washed away and identity reshaped. This is where the Lebenswelt matters: the bathhouse is not an abstract concept but a lived world, a horizon in which spirits, bodies, and communities meet.

Bulgaria, and South Slavic cultures generally, don’t have banniki, but they do have various other spirits playing similar, liminal roles. For instance, the Домовник [Domovnik] or Стопан [Stopan], who are a kind household spirit, guardian of the home. While they are connected to hearth and prosperity, they are yet never fully assimilated into this household, instead inhabiting threshold zones just as the bannik did, hearth, barn, yard corners, places between inside and outside. They mediate prosperity and misfortune, embodying a house’s fragile and vague boundary with the wider world. More on topic, are Русалки [Rusalki], female water spirits linked with rivers and springs. These beings could heal or harm, especially around the feast of Rusalska Nedelya (in early summer). Thus they, like bannik, appear during liminal times such as this feast, which takes place in the “unclean days” after Pentecost, when the boundary between living and dead blurs, a typical mélange of Christian and Slavic folk religions. They dwell in rivers and springs, transitional zones between earth and water, and lure humans across that boundary (good work, if you can get it). Finally, there are the notorious Самодиви [Samodivi], wild forest maidens, often associated with streams and mountain springs. These feral beings are quite dangerous if offended, but, like the springs they protect, could also heal. These maidens inhabit an ultimate liminal zone, the border between nature and culture: beautiful women, who are yet nonhuman and perilous. Encounters with them often occur at dusk or dawn. They still haunt the wooded areas of the Bulgarian mountains, at least according to no less than two acquaintances of mine who claim to have had dangerous encounters with these creatures in the forest around nightfall; I remain skeptical.

What unites these scenes from the bathhouse as a site of peril and renewal, to Slavic spirits who haunt thresholds of house, water, and forest, are their shared emphasis on liminality. To cross into steam, into a river haunted by rusalki, or into a glade patrolled by samodivi is to risk the self, and in that risk, to renegotiate belonging. That is, these thresholds mark who is inside or outside, protected or exposed, kin or stranger: who belongs and how to identify them.

Bathing thus became a drama of identity as much as of cleansing, with roots reaching far before Slavic folklore, into the Roman world. Michal Zytka, in A Cultural History of Bathing in Late Antiquity and Early Byzantium (2019), argues that bathing became central to defining what it meant to be Roman. Garrett G. Fagan, in Bathing in Public in the Roman World (2002), similarly notes that Roman thermae functioned as community hubs. These evolved from Greek loutra and simpler Thracian bathing practices into the more elaborate Roman thermae. Where Thracian baths were small and functional, Roman thermae were complex, decorated buildings with extended bathing rituals that encouraged socializing. People met friends, held informal gatherings, and politicians used the baths to win support. Beyond bathing, thermae included libraries, reading spaces, brothels, areas for eating, and shopping. They were essentially a combination of library, art gallery, market, restaurant, gym, and spa. In many ways, bathing became the “wet wing” of Roman imperialism: its civilizing mission aqueous, flowing outward through conduits of stone and ritual, seeping into conquered lands until bathhouses stood as outposts of Roman order across Europe and North Africa. Water carried not only cleanliness but discipline, architecture, and hierarchy—a liquid architecture of empire spreading as surely as legions.

The point is comparative but crucial. In Rome, baths made you civilized, enrolling you into the order of empire. In Slavic folklore, baths and their thresholds drew you into a world alive with spirits (domovnik guarding hearths, rusalki haunting rivers, samodivi at springs and glades) where danger demanded ritual caution and respect. In both settings, bathing worked as a kind of Bildung: incarnate schooling in how to belong, teaching the small gestures and shared habits that mark identity, showing that you act as others do, and can you please pass the soap?

And it is this inheritance — part Roman, part Slavic — that Vazov drew upon when he turned to Sofia’s mineral springs.

3. Vazov in the bathhouse

So, let’s return to Vazov, who, in “In the Warm Waves”, situates Sofia’s mineral baths in a lineage that runs from Rome through medieval Bulgaria, but never through the Ottoman Empire:

Historical annals say nothing about which Roman emperor first built the mineral bath in our capital, Sofia. Yet the truth is that this blessed water was known long ago, gathered into basins and crowned with vaulted arches even in the earliest days of Roman rule on the Balkan Peninsula. These pleasure-loving Roman conquerors, enchanted by the luxury of conquered Asia, were ardent devotees of the baths – a place for political intrigue, celebrations, and indulgent revelry, as Sienkiewicz recounts in his novel Quo Vadis? It is no less true that Sofia owes its very existence to these warm springs at the foot of Vitosha; at one point, they nearly tempted Constantine the Great to make it the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. Perhaps it was these very precious waters that, in 805, drew Krum and his wild hordes, so that Sofia became among the first to fall beneath his blows. And when we sit by its fountain, letting the hot streams wash over our shoulders, we scarcely imagine that, eleven centuries ago, our fierce, great, and passionate tsar may have stood in the very same place, doing the same; that perhaps even his harem frolicked in these waves, sharing in the same pleasure and bliss that we feel today.1

This is not just description but also performance. Vazov invites us into the Lebenswelt of bathing: the reader is not just told about history, but asked to feel it, to imagine Krum’s harem frolicking in the same water that now washes over “our shoulders”. It is embodied history, an invitation to inhabit identity through sensation, through taking time to do the same thing Vazov did in this banya, a banya which every citizen of Sofia can still go and visit.

But it is also an act of forgetting. Ottoman hammams, with their centuries of architecture, medical traditions, and rituals, vanish into steamy air. The genealogy runs from Thrace to Rome to Byzantium to Bulgaria, as if the Ottoman centuries had never happened. Vazov’s waters cleanse not only the body but the past, leaving a purified line of descent that makes Bulgarians heirs of Rome. The absence of Ottoman hammam is itself a lesson in the politics of memory and the shaping of the lived world.2

The invocation of Rome is no accident. As Alain de Lille wrote centuries earlier: mille vie ducunt hominem per secula Romam: “a thousand roads carry man, through the ages, to Rome”. Vazov chooses one such road for Bulgaria and closes others. In this sense, the bathhouse becomes more than a place to soak: it becomes an archive of memory, a site where identity is curated, impurities rinsed away, and a nation emerges clean, steaming, and (somehow) Roman.

4. Identity, continuity, forgetting

There is something striking, maybe even unsettling, about Vazov’s “In the Warm Waves”. For all the richness of his historical imagination, his essay flows too easily past centuries of Ottoman bathing traditions, as if their presence had simply evaporated in the steam. Instead, he gives us Rome, Constantine, Khan Krum, and the proud Christian, European Bulgaria of his own day. What is absent is just as telling as what is present.

This erasure makes sense in context. Vazov lived through the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), the struggle that finally pushed the Ottoman Empire from Bulgarian soil. He did not fight with rifle in hand, but his pen was no less a weapon: his works, especially Под игото [Under the Yoke], thunder against Ottoman rule, glorifying the agonies and triumphs of liberation. For a man who had made a career memorializing resistance, the hammam was too intimate, too ordinary a reminder of the empire he was writing against. Better, then, to wash it away, to soak instead in a genealogy that ran back to Rome and medieval tsars.

And yet Ottoman traces are everywhere, even when scrubbed from the page. One only has to look at the ubiquitous чешмата [cheshmata: fountains] scattered across the land. The very word comes from Ottoman Turkish çeşme, itself from Persian čashmeh, meaning “spring” or “source”. These fountains dot every village, mountain road, and city park, offering mineral waters whose sources predate nations and wars alike. To drink from them is to sip a layered past, whether one acknowledges it or not. Ever Bulgarian carries a few empty plastic bottles in the trunk of their car, just in case they find themselves near a treasured chesma that carries their favored natural “brand” of mineral water.

Two contemporary scholars, Ivo Strahilov and Slavka Karakusheva, remind us that baths and fountains are not just infrastructure but what they call “hydrosocial heritage”. In their study of the village of Banya (near Razlog), they show how the destruction and privatization of local baths tore holes in communal life. The pools were not merely places to wash or soak; they were woven into rituals of belonging. Villagers recalled, for example, how fathers would fetch warm mineral water each night to bathe newborns, a tradition said to be centuries old, a baptism not into a church but into place itself. As one woman, of about 65 years, mentioned in 2022:

Another tradition that is kept even to this day is that when a baby is born, it must be bathed every evening in mineral water. My God! Every evening the fathers… A tradition… They go, draw warm mineral water, and the babies are bathed in the bath with mineral water. This is a centuries-old tradition and will probably last for centuries more. Along those spouts in the evenings the fathers go and fill up water to bathe the babies.3

This memory, simple and concrete, does more than any theory to show what is at stake: to bathe a child in mineral water is to root them in place, to bind them to community and earth. The act is intimate and ordinary, yet also cosmic in its insistence that belonging is born in the waters themselves. Wet metaphysics, humid cosmography.

For me, as someone who did not grow up with these waters but has bathed in them for more than a decade, this layering is palpable. Bulgaria’s baths feel both deeply local and uncannily global. They carry myths from Thrace to Rome and centuries beyond, all condensed into the sensation of hot mineral water on skin. They are living palimpsests, but also fault lines, where the politics of remembering and forgetting are fought not only in books and laws but in the very names of the baths, in the cracks of their tiles, and in the stories told in clouded air.

In this sense, Vazov’s omission is not merely historical oversight but part of a long tradition of selective memory, for remembering is always to trim, to frame, to forget. Baths have always been places where impurities are washed away. For Vazov, those impurities included centuries of Ottoman influence. For modern developers, they include shabby socialist buildings. For villagers, the impurities may be the forgetfulness itself. Each era rinses the waters differently, but the act of bathing — of cleansing identity through immersion — remains the same.

5. Socialist waters and scientific spas

If Vazov rinsed Ottoman hammams from the page to re-anchor Bulgaria in Rome, socialism baptized the waters in another register altogether: science. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, even before socialism proper, Bulgaria codified its mineral wealth into law. In 1891, the state issued legislation to protect mineral springs, a recognition that these waters were not just folklore but national resources.4 With the socialist era, this impulse crystallized into an entire institutional apparatus devoted to the therapeutic and ideological management of water.

By 1949, Bulgaria established the Scientific Institute of Balneology, Physiotherapy, and Rehabilitation [Научен институт по балнеология, физиотерапия и рехабилитация]: a name so long it sounds like it was designed to impress even before it cured. The mission was serious: establish, with laboratory precision, the ways in which mineral waters, muds (forget not the humble peloid!), and gases could be harnessed for public health. It was not enough that hot water felt good on aching joints; balneologists sought to measure its effects on blood, nerves, skin, stomach, and maybe even soul, properly interpreted materially, of course, or metaphorically as “the soul of the people”.

This was more than medicine. It was ideology in liquid form. Socialist balneology reframed the bathhouse not as liminal folklore or bourgeois leisure but as an arm of the state. Health was a collective good; the waters belonged to the people. To be a socialist citizen was to be well, and to be well was, sometimes, to spend three weeks soaking on doctor’s orders at a state-run sanatorium. The ritual of the bath thus became a ritual of socialism itself: equalizing, universal, rooted in nature, but directed by science.

And it worked, at least in part. Anyone who has spoken to older Bulgarians knows the nostalgia that still clings to those days when a prescription might send you not to the pharmacy but to Velingrad or Sandanski, there to take the waters under the watchful eye of both physician and Party. Balneology offered a kind of earthy utopia: natural resources transformed into public health, ancient waters repurposed for the future.

Yet, like Vazov’s selective memory, socialism had its own silences. The hydrosocial heritage of Roma communities, with their oft distinct bathing traditions, was sidelined. Folk rituals that smacked of superstition were ignored or rebranded in scientific language. Anything that did not fit the paradigm of measurable therapeutic benefit was, at best, tolerated; at worst, suppressed. What remained was a vision of water as resource: quantifiable, categorizable, state-owned.

Still, the system was nothing if not ambitious. Bulgaria is practically leaking mineral water, with somewhere between 520 and 700 identified springs, their temperatures ranging from a refreshing 10°C to a scalding 103°C, enough to boil an egg or a reckless bather (or, if the bather is hungry, both). Only Iceland rivals Bulgaria in sheer abundance in Europe (at least, according to some estimates; others have Hungary in second place). Socialism took this embarrassment of riches and mapped it to medical need: sulfurous waters for skin ailments, iron-rich for blood, mildly radioactive for nerves (don’t panic, you get more exposure on a flight from Sofia to London). If you had a bad stomach, aching joints, or mysterious rash, there was a Bulgarian spring ready for you, bubbling away patiently, a natural, socialist pharmacy in fluid form.

It is easy to poke fun at this project, perhaps, but there is something profoundly modern, even admirable, in the attempt to knit together geology and physiology, to put nature in service of collective health. In the age of antibiotics and CT scans, balneology might seem quaint, yet it spoke to a holistic vision of medicine that is increasingly relevant again. Long before “wellness tourism” became a capitalist catchphrase, socialist Bulgaria had made wellness an entitlement, a birthright secured by the state. And, as it happens, much of this balneal medicine has been shown to have real therapeutic effects, if often more modest than claimed by Socialist proponents.5

The irony, of course, is that this scientific baptism did not make the waters less mythic. If anything, the layering deepened: socialist sanatoriums merely pouring another story into an already overflowing pool. It is inescapable, and even today, to step into a Bulgarian mineral bath is to be immersed in this sedimented history, at once clinical and magical, national and personal, ideological and elemental.

6. (Bottled) waters under capitalism

If socialism collectivized the baths, capitalism commodified them. Since the 1990s, the fate of Bulgaria’s mineral springs has been a story of privatization, neglect, and occasional rebirth in the glossy language of “spa tourism”. Many once-public pools have been fenced off, leased to private developers, or simply abandoned, their peeling paint and broken fountains testimony to what happens when ideology dries up and market logic seeps in.

The story Strahilov and Karakusheva tell is emblematic. In their study, the destruction of local baths is not just the loss of infrastructure but a rupture in communal life. The baths were a social commons, a space of gathering and tradition, where generations soaked in continuity. Their closure or privatization left more than empty pools; it left gaps in memory, belonging, and identity. As the authors note, these losses sting all the more in the Balkans, where “gangster capitalism” has often meant the appropriation of public goods for private gain under a thin veneer of legality.

Naming practices matter. Where villagers once spoke of the stara banya (“old bath”) or even the “Turkish bath”, new developers prefer “Roman bath”, with its connotations of grandeur, antiquity, and above all marketable Europeanness. The shift echoes Vazov’s own silences: just as he rinsed the Ottoman hammam from his essay, so too do contemporary entrepreneurs scrub away Ottoman associations to make the baths palatable to tourists. A Turkish bath can be too near, too recent, too Eastern; a Roman bath, by contrast, is exotic enough to attract visitors, but familiar enough to feel civilized. As Strahilov and Karakusheva argue, such renamings are not just marketing tricks but acts of memory and identity politics, shaping who belongs and who does not, what is honored and what is erased.

Yet older residents resist this erasure. Some still speak proudly of the “Turkish bath”, not as a mark of subjugation but as a memory of community life, of the way water once bound villagers together. Here, the politics of memory collide: for one group, Ottoman traces must be scrubbed; for another, they remain part of lived heritage. The bath thus becomes a contested archive, where every name — Turkish, Roman, Old — carries a politics of remembering and forgetting.

Capitalism has brought other distortions. Where forest spirits and ancient rituals promised access to mountain springs, now there are spa memberships and payment plans. Where socialist sanatoria promised near-free care for ailments, today’s spa resorts promise wellness, at a price. What was once a right of citizenship is now a luxury experience, packaged in glossy brochures with English slogans and five-star ratings. Mineral water, once the most democratic of substances, becomes stratified: bottled, branded, and sold in supermarkets; fenced, ticketed, and marketed to tourists in resorts.6

And yet, as with Vazov’s nationalism and the Communist Regime’s socialism, capitalism cannot completely capture the waters. People still find ways to soak in the commons: half-ruined pools that locals keep alive with buckets and concrete patches, piled stones and hard work, hidden spots in forests where mineral springs bubble out of the earth, improvised baths where thermal pipes meet the sea and where villagers gather despite official neglect. These improvised hydrosocial spaces resist commodification precisely because they are too small, too shabby, too ordinary to monetize.

The result is paradox. Capitalism both erases and preserves: it erases by renaming, privatizing, and excluding, but it preserves through neglect, by leaving spaces too marginal to be worth the effort of enclosure. In these overlooked corners, the stubborn traditions of hydrosocial heritage persist: fathers still fetching water for newborns, neighbors still meeting in the damp warmth.

If Vazov’s selective memory was a literary act, and socialism’s a scientific one, capitalism’s is a commercial one. Each in its own way “washes” the waters, rinsing some pasts and highlighting others. But the water itself keeps flowing, refusing to be contained by any single narrative. In the interplay of public and private, memory and forgetting, what remains is the lived fact of hot water: soothing joints, softening divisions, fogging glasses.

7. Lived belonging in the bath

Amid all these grand narratives, from Vazov’s literary cleansing to socialism’s scientific baptisms, and of course capitalism’s glossy commodifications, what persists is the stubborn, sensuous fact of hot water. The mineral bath is not just a site of history; it is a site of belonging in a deep physical, sensuous sense. It is also a liminal zone, a threshold space where ordinary social boundaries and everyday identities are suspended, and participants exist in a state of transition—between work and leisure, private and public, self and community.

My own experiences in Bulgaria confirm this. As I mentioned above, I first encountered banya culture not in the Balkans but in Manhattan, in the Russian-Turkish Baths of the East Village. There, in dim dubiously cleaned pool rooms with their suspicious smelling miasmas, I found something resembling what I would later experience across Bulgaria: old men comparing aches and memories, young men bragging, massive Slavic masseuses offering to smack the hell out of you with birch branches (веник [venik]), everyone sweating and soaking together. Yet if New York’s baths felt like a seedy fly-by-night joint, Bulgaria’s are the full inheritance: centuries-deep, layered with Thracian myth, Roman ruin, Byzantine continuity, Slavic myth, Ottoman hammam, socialist sanatorium, capitalist spa.

Take Ogyanovo, near Leshten in Blagoevgrad oblast, my favorite of Bulgaria’s plethoric baths. A product of the socialist period, it was once a free outdoor pool, always full: pensioners easing joints by day, teenagers sneaking in bottles of rakia by night. When I first visited over a decade ago, the place was alive with chatter and the gurgle of flowing water, a crossroads of generations. A flood in the early 2020s damaged the pool, and the reconstruction that followed stripped some of its charm, not least because it was no longer free. Still, the waters remain superb: over 40°C, mineral-rich, soothing in ways physical and psychological.

The bath also carries its own mythology. Locals tell stories of St. Paul blessing these waters during his travels through the region, though the historical record suggests he never made it quite so far, staying instead in northern Greece around Philippi. More plausibly, the nearby city of Nikopolis ad Nestum, founded by Emperor Trajan in 106 CE, likely explains why this region hums with Roman echoes. Yet the myth matters as much as the archaeology: to bathe here is to bathe in stories, in layers of belief that span centuries.

And then there is the social alchemy that sometimes occurs in the banya. Ogyanovo is the only place in Bulgaria where I have personally seen Roma and Bulgarians share space with something like civility. This may sound like a small thing but given the virulence of anti-Roma prejudice in the country, it borders on miraculous. Perhaps a bath is uniquely suited to this kind of coexistence, the wisdom of Rome’s multiuse thermae renewed. In the humid air, stripped of clothing and social markers, bodies are softened, differences blurred. The mineral waters are indifferent to ethnicity, and that indifference makes possible moments of fragile community.

This, to me, is the real politics of bathing. Beyond literary cleansings and state-sanctioned protocols, beyond tourist brochures and capitalist enclosures, the bath persists as a place where people gather, grumble, gossip, and occasionally transcend their divisions. It is not utopia — prejudices don’t evaporate — but it is a suspension, a temporary reprieve. It is, in essence, a threshold between the pressures of daily life and the temporary community forged in heat and water.

To belong, then, is not always to wave a flag or recite a national poet. Sometimes it is simply to sit shoulder-to-shoulder in a vaporous pool, to close one’s eyes as sulfur rises in the nostrils, to feel muscles loosen and pores open, to be carried together by the same ancient waters. Belonging here is bodily, not abstract; lived, not theorized.

8. Being

Bulgaria’s baths are not just about hygiene, nor even about health, though aching joints and mysterious rashes do find relief. They are about being in the most literal, embodied sense. They offer a Lebenswelt: the lived world before conceptualization and reflection, where meaning is not thought and analyzed, but soaked, not spoken, but inhaled. In the bath, one dwells in a liminal space, straddling work and leisure, local and foreign, past and present, dry and wet, where bodily experience shapes both perception and identity.

This is why Vazov matters. His “In the Warm Waves” is not just literary description but a performance of Lebenswelt. To let the streams wash over one’s shoulders is to feel history in the body, to experience belonging not as an idea but as a sensation. And this is also why his silences matter. By leaving out the Ottoman hammam, he performs another act of bathing: a national purification, a scrubbing of memory. In the bath, impurities are washed away. For Vazov, those impurities included centuries of Ottoman life.

Socialism, too, staged its own Lebenswelt: a world in which citizens immersed themselves in mineral waters under the guidance of doctors and the sanction of the state. Capitalism followed with its glossy spas and bottled waters, now rebranding Ottoman traces as Roman allure. Each era reshaped the waters to fit its horizon of meaning. But the bath itself — hot, mineral, insistent — continued to flow, refusing to be captured by any single ideology.

And then there are the lived moments that defy abstraction: teenagers passing a bottle of rakia under the stars in Ogyanovo; an old man sighing as he lowers himself into sulfurous warmth; Roma and Bulgarians, locals and foreigners, men and women, for a fleeting hour, sharing space. These are not theories of identity but practices of it. They are Bildungof another kind, an education in heat, sweat, water, bodies floating next to bodies.

To bathe, then, is to inhabit the Lebenswelt in its purest form: to feel continuity and rupture, forgetting and remembering, solitude and community, all at once. It is to step into a liquid archive where Thracians, Romans, Slavs, Byzantines, Ottomans, socialists, and capitalists have all left their traces. And it is to discover, in that archive, not only who Bulgarians have been but who they might yet be.

Perhaps this is how the baths endure. They remind us that identity is not only narrated in epics or legislated in institutes, but soaked into muscles and bones, shared in damp heat. Carried in water.

Ivan Vazov, “In the Warm Waves (Bathing Observations)” [1881], Stories 1881–1901, Sofia: Bulgarian Writer, 1901 [Вазов, Иван. “В топлите вълни (Бански наблюдения)”. В Разкази 1881–1901, 1–4. София: Български писател, 1901]; see an electronic edition here.

For an interesting discussion of the impression Ottoman baths made on Christian visitors in the 16th to 18th centuries, see Tsvetan Radulov, “Османските бани през погледа на християнските пътешественици [The Ottoman Baths through the Eyes of Christian Travelers]”, Семинар_БГ (2024), 27.

Quoted in Ivo Strahilov and Slavka Karakusheva, „Сровени“ спомени: приемственост и разруха в хидросоциалното наследство на разложкото село Баня [Memories “in Ruins”: Continuity and Destruction in the Hydrosocial Heritage of the Village of Banya], Семинар_BG, 2024.

For background and a case study of this process of resource institutionalization, see Violeta Kotseva, “Развитие на балнеолечението в гр. Кюстендил в началото на ХХ в” [Development of balneotherapy in the town of Kyustendil at the beginning of the 20th century], Семинар_БГ 27 (2024).

See, for instance, Héctor García-López et al., “Effectiveness of balneotherapy in reducing pain, disability, and depression in patients with Fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis”, International Journal of Biometeorology 68.10 (2024): 1935-195.

For more detail on how these changes affect groups like the Roma, see Rositsa Kratunkova, Обществени бани: социализация, разпад и съпротива [Public Baths: Socialization, Decay, and Resistance], Семинар_БГ (2024).

Thank you Benny Goldberg, for this beautiful plunge into "wet metaphysics" and "hydrosocial spaces" of Bulgaria. In opens up an entire Slavic world I had no idea of : what bathing can mean in terms of identity, history and politics. And how the bathing tradition is deeply ingrained into the people's bodies.

Wonderful! As it happens, I'm re-reading Patrick Leigh Fermor's The Broken Road, about Bulgaria and Romania - and seeing a reference to the atrocities of the April Uprising (1876), looked them up, and was horrified and saddened...the events must have left deep scars on Vazov and his generation. Also, it seems in Romania (where I have visited and have friends), the distant Roman-Dacian heritage offers a way of living with the past which can stitch together some of the 19th-20th-century divisions into Hungarian, German, Romanian, Transylvanian, and Roma - not to mention the recent communist memories.