Comments are open.

Are your reading skills getting rusty? Then click here to listen to the audio version instead!

1.

With the US Supreme Court’s recent decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the decades-long dialogue des sourds concerning the moral status of foetuses has attained new heights of futility. Some who regret the decision have adapted the “trust the science” piety lately honed in an epidemiological context to return to what they take to be a settled embryological fact: that there is no good scientific basis for the presumption that an early-term foetus is a suitable candidate for moral personhood, since its level of neurophysiological development is insufficient to warrant any attribution to it of a capacity to feel pain. This presupposes however that personhood is won by candidates for it through an investigation of their physical constitution, and that it can be directly “read off of” the arrangement of their parts and the capacities known to depend on that arrangement.

In some cases, indeed, personhood is attained in just this way — for example, the legal recognition of great apes as persons in some jurisdictions, in view of the scientific consensus that, given their neurological complexity, there must be something of moral interest going on behind a gorilla’s eyes. But in actual fact this is only one way to go about establishing personhood. There are mountains in Bolivia that are now legally persons, for example, and a river in New Zealand. These developments reflect an inchoate concern to honour in law the spirit of Indigenous representations of the natural environment, but they are also pragmatic. Most lawmakers likely do not believe that rivers can in fact be persons, while also hoping, perhaps, to come across as committed to Indigenous issues by acting as though they can be.

When we move from jurisprudential determinations to a consideration of the different symbolic systems in which entities show up as valuable across different cultures, we find many “inanimate” objects taken as loci of supreme value, as charged up with a moral significance as great as that of any adult human individual, yet that from the outside look like mere fragments of wood or stone. An Aboriginal Australian tjurunga, for example, a ritual object that encodes the life of a person or a group, is taken in certain respects to be the epitome or the true vehicle of that life. It is a charged object, kept out of sight of most members of a community, who for their part come and go in this world of flux while the tjurunga stays put. The tjurunga is the utmost object of care, even as it remains, from a certain point of view, a mere piece of wood.

In Polynesia, rather than encoding the key moments of a person’s life into an external object, these moments get inscribed, along with the individual’s broad cosmological and kinship-related “bearings”, into their very body as tattoos. But whether the key moments and bearings are externalised in an outer object or “incorporated” into the body itself, there is a world of meaning and value that is tracked in these markings — something like the “name, rank, and serial number” of a soldier’s dog-tags, if these were amended and lengthened until they told the whole epic of their bearer. And it is this activity of tracking itself, of caring, that generates the value, rather than any pre-given constitution of the thing that is valued.

In trying to derive moral value from neurophysiology, contemporary moral philosophy still hopes to squeeze an “ought” from an “is”. You can’t get blood from a stone, or from a tjurunga, but there is another less invasive way of discerning what is of value — by following, namely, the production of value in culture.

2.

Is a foetus a person, or is it a morally irrelevant stub of a person, as one woman at a pro-choice rally recently contended, even going so far as to write the words “Not Yet a Person” on her rounded belly — inscribing, like the Polynesian seafarer, at least a hint of her cosmological bearings directly into her body?

Many have noted over the past week that the American right only discovered its supposedly deep concern about the lives of foetuses very recently. Where was that concern before? they want to know, and they presume that if it has a recent history this can only be because it was latched upon in bad faith as a political wedge, and cannot be underlain by any real moral conviction. But the problem with this ironically rather conservative expectation, that any moral conviction needs to be continuous with the moral convictions of our ancestors, is that nothing, in the contemporary world, is as it used to be, and we find ourselves in nearly every domain of life scrambling to cultivate, or at least pretend to hold, moral convictions that are often nearly or totally without precedent.

As a general rule about the history of humanity, we may say that people kill people, and they definitely kill animals. We may recognise this, and still find that it offers little instruction as to whether or not it makes sense, now, for humanity to transition to a plant-based diet. Answering this question, on a planet hosting eight billion people and even more cattle, has nothing to do with the pseudo-question of whether “it’s wrong to kill animals” in some timeless way that applies both to those profiteering from factory-farming and to Palaeolithic hunters alike.

We may, likewise, acknowledge the significant historical evidence for the relative absence of controversy surrounding abortifacients in medieval and early modern Europe, the casual acceptance until recently of miscarriage (or “abortion”, as it was called) as a part of reality and the corresponding unwillingness to treat a foetus or an infant prior to baptism —that is, prior to ceremonial intake into the community— as a full-fledged moral person: we may acknowledge all this, and still be left uncertain in our view of the legacy of Margaret Sanger or of the use of ultrasound for sex-selective abortion in India.

3.

If, as for medieval Europeans, it’s the postnatal ritual of baptism that marks the instant of promotion to the ranks of persons, then indeed the loss of a pregnancy or even, perhaps, the exposure of an unbaptised newborn, may not be experienced as tragedies. These concern entities that are “not a person yet”. But rituals change, and with them the ways in which moral status is produced.

One particularly regrettable gap in the generally grossly impoverished conflict over abortion is the absence of any discussion of the role of technological change in the transformations of our rituals for the production of personhood. It is not that no one has written about this, of course, just that those who do write about it have trouble getting others to care. The historian of medicine Barbara Duden, notably, has spent a long career arguing that, in its own way, the ultrasound is up there with the microscope, the telescope, and the electron cloud chamber among the instruments that have fundamentally transformed the way we see our place in the world.

In antiquity and the middle ages (of course with significant exceptions in various centuries and contexts), the human viscera were often conceptualised as beyond the bounds of observability. Even if they were seen inadvertently as a result of accidents or war, and even if they could be analogically imagined from the observation of animal innards, there was both a cultural taboo as well as a near-constant practical limitation on the possibility of looking at the inside of the human body.

These moral and practical boundaries were at their strongest in relation to the uterus, a standard synonym of which, in Latin, was matrix — a word that reveals its connection to motherhood even on the most casual etymological consideration. This is the same word that was commonly used for subterranean caverns and shafts in which crystals and minerals were formed. The most common view in antiquity, as expressed for example by Pliny the Elder, was that miners were just asking to die of poison-gas inhalation, since in effect to go down into the earth in search of riches was nothing less than a form of rape. We see this prohibition beginning to lift in Johannes Agricola’s De re metallica (1556), and in light of this early, narrowly mineralogical shift we are perhaps better able to understand the full significance of Francis Bacon’s admonition to researchers a half-century later violently to penetrate into nature, in their search after truth, wherever its secrets may be hidden. Thus Bacon writes in The Advancement of Learning (1603):

For you have but to follow and as it were hound nature in her wanderings, and you will be able when you like to lead and drive her afterward to the same place again… Neither ought a man to make scruple of entering and penetrating into these holes and corners, when the inquisition of truth is his whole object.

Over the following decades, two parallel processes would unfold. First, there is what we may call the dematricisation of the Earth; G. W. Leibniz for example will argue repeatedly in the 1690s that geological phenomena must in no way be seen as subject to the same laws as animal and human generation. Second, in the sciences of generation, researchers following broadly in Bacon’s spirit will find every way imaginable to enter and penetrate into animal matrices to better understand the nature of living beings prior to their birth.

Already from the Renaissance, researchers had conducted observations on fecundated bird eggs at different points in their development to better understand avian generation. After Bacon’s call, some would move on to observations requiring considerably more assertive interventions in the course of nature. William Harvey, for example, in his Experiments concerning Animal Generation (1651), will describe in great detail the results of a series of experiments he conducted on pregnant deer. The English experimentalist monitored their likely dates of conception, and then cut them open sequentially at different intervals of their pregnancies, effectively seeing the freshly dead foetal fawns as time-slices or freeze-frames of mammalian gestation. Whatever knowledge may have been derived from this bloodbath to make it “worthwhile”, it is hard not to agree with feminist scholars such as Carolyn Merchant that what we are witnessing here really is a rape of nature, however rationalised, however sublimated the violence of it through the laundering process of scientific method.

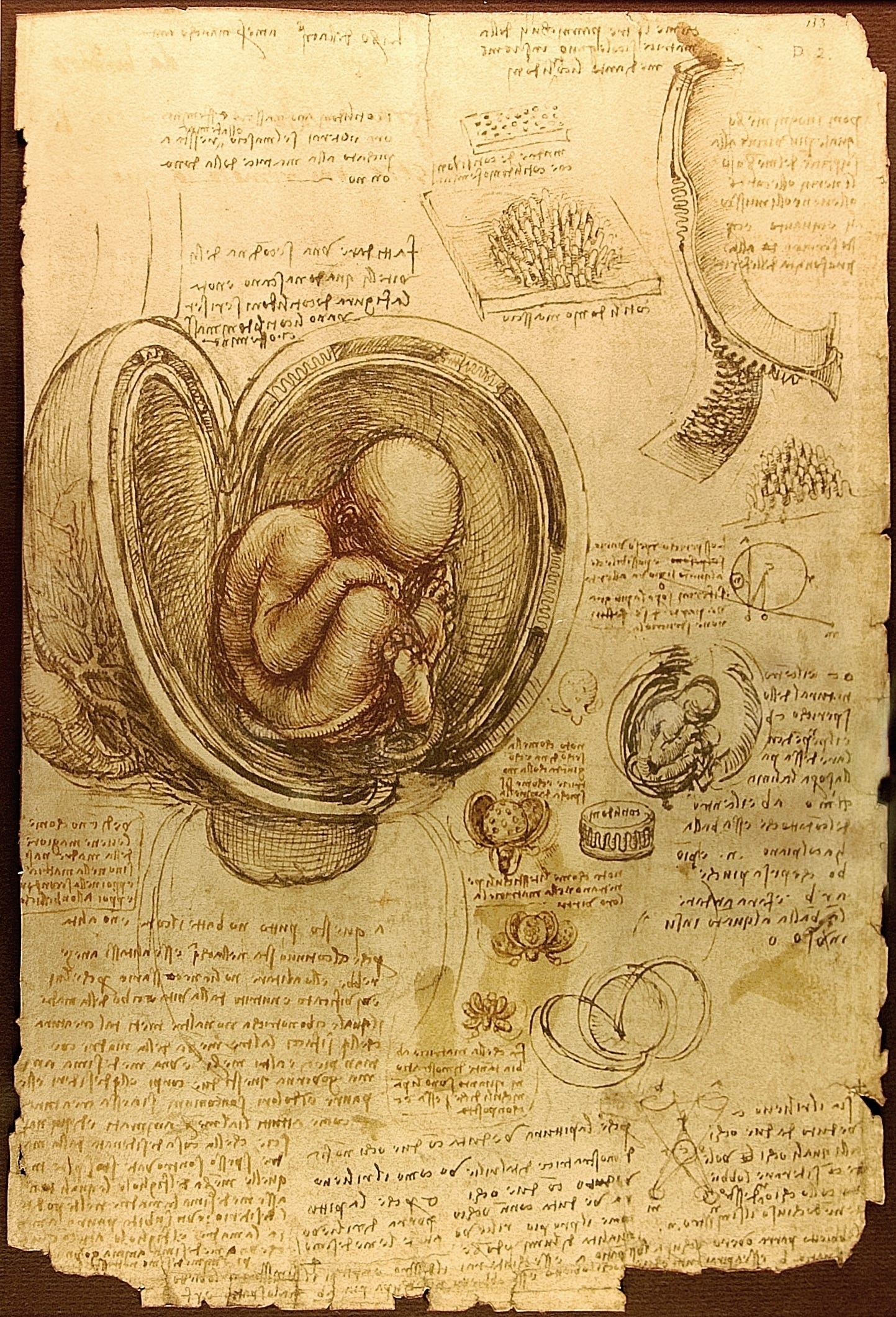

In parallel, over the course of the same century representations of the human foetus became a far more familiar feature of visual culture. René Descartes, for example, tried his hand at drawing one, though of course in this he was preceded by more than a century by the prophetic Leonardo da Vinci. By the end of the eighteenth century naturalists such as Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, along with his son Isidore, had come up with a new and less invasive means of seeing what can ordinarily not be seen: the science of teratology, namely, which observes and classifies the various types of birth-defect that often result in premature exit from the womb, revealing not just the abnormalities in the body that previously researchers considered too rare to be informative, but also the ordinary course of development, at different stages, of parts and systems of the body that are not affected by the defect in question.

But the “Copernican turn” in the history of our coexistence with foetuses would only arrive with the introduction of ultrasound technology in the mid-to-late twentieth century. Tellingly, this occurred around the same moment that we also received the first photographic images of the Earth taken from space, thus giving rise to the “pale blue dot” cliché and, one might argue, to a new object of moral concern. This is not to say that no one loved the Earth before it could be represented in its totality as a high-resolution image, but only that the particular form of solicitude for it that began to make itself heard, as a sort of character in human history, as so to speak a person, is the result of transformations in our technologies of seeing.

And likewise with the foetus, which, whatever its neurophysiological complexity, whatever the quality of its inner life, has without question become a significant social actor over the last half-century since ultrasound technology became widely available. This is certainly so for anti-abortion conservatives, who have been accused of opportunistically taking up this new object of care they previously neglected, while in fact their apparent opportunism derives from the fact that they are, like all of us, encountering a social actor who had previously got significantly less “stage-time”. And it is no less true for pro-choice progressives, who are often happy to “personify” ultrasound images of the foetuses they choose to keep, calling them “cute” or delighting in the arrow that points at their “gender”, perhaps posting it on social-media, in ways that would have been simply impossible before the present era.

4.

Elizabeth Harman has attempted to argue that foetuses designated for abortion have no moral standing, even if their foetal coevals, chosen for birth by their parents, do have moral standing, since that standing is something that only becomes retroactively valid for the foetus in virtue of its future life as a postnatal human being — a future life that the foetus designated for abortion does not have. But this argument, whatever else may be said of it, seems to be somewhat weakened by the fact that choices are sometimes made about abortion in light of information obtained through the technologies that bring foetuses forward as social actors. That is, it is the same technology that both enables you to frame a print-out of the foetus to place on your desk in anticipation, and at the same time to discover the birth-defect that will make you judge, in line with your society’s norms, that any future life for this foetus will not be worth living. At a much larger scale, this is also the technology that enables prospective parents to cut short the lives of millions of potential women, the common term for which is —refreshingly, in our era of unrelenting euphemism—, “female infanticide”. It is indeed hard to conceptualise sex-selective abortion in any other way, since the technology that is being used to determine whether the abortion is to be carried out or not is also the one that reveals the foetus to be a particular kind of human, namely, a girl, rather than simply a foetus incognitus, an unseen abstraction.

I am not saying anything “for” or “against” abortion here. I do not use this space for advocacy. As it happens I think the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade was horribly wrong, and yet another symptom of the decline of participatory democracy in the United States. I also think it is wrong to straw-man your opponent’s arguments, as happens whenever a pro-choice person says that the opposite position can only come from a desire to control women’s bodies, rather than from what at least feels like a sincere conviction about the moral status of foetuses; and I especially think it’s wrong to talk past one another, as for example when an abortion-defender says “My body, my choice”, and a pro-life person responds “It’s a child, not a choice”, and so on ad nauseam.

The problem here is that we, as sexually reproducing animals, are simply thrown into the world with a complication that does not sit easily with our late-arriving commitment to individual bodily autonomy. Pregnancy is a sui-generis predicament, and it will do no good at all, in seeking to arrive at an understanding of its nature or how to resolve the moral conflicts it generates, to invent wild thought-experiments, as Judith Jarvis Thomson sought to do, about being kidnapped and attached to a maestro violinist for whom you are uniquely suited to offer, with your body, an emergency sort of kidney dialysis. It’s not the same, obviously. Nothing is the same as a foetus, in fact. There is no entity in human biological or social reality that presents the same set of problems, not just for morals, but indeed for metaphysics.

To acknowledge that the foetus is sui generis says nothing at all about what may be done to it, or what it is. A person? Not a person yet? I am certainly not going to tell you.

What I will tell you, first of all, is that personhood is just not the sort of thing that can be read off of a brain or nervous system. In cultures that practice banishment, you can be a fully adult human being and have your personhood stripped from you; in others, idols of stone can be persons. What makes a person a person, then? Care. How do we know what sort of thing to care for? We decide.

Second, I will tell you that it is precisely the same techno-social transformations that caused both the rise of the contemporary anti-abortion movement on the right, and the broad cultural attitudes and representations of pregnancy within which abortion is advocated and sought out, whether by people who think the time is just not right, or by people who think they would really rather have a male first-born.

Many people on social media have expressed the view, endorsed by Edward Snowden, that the difference between the pre-Roe and post-Roe suppression of legal abortion in the United States is that we currently “live in an era of unprecedented digital surveillance”. There has thus been a frenzy of warnings to women to delete their period-tracking apps, and any other digital trace that might be used against them should they travel illegally for an abortion where it is still legal, or get an illegal abortion where they reside. But what the Snowden-approved tweet leaves out is that it was already surveillance, in a large sense, that gave us the controversy over abortion in its contemporary form. The simple operation of seeing the foetus in utero, an operation made possible by a prior desire to see that was always as irrepressible as it was taboo, leads inevitably to a system of monitoring, in the name of reproductive health, and in turn to a system of control.

5.

The name of this essay is a fairly obvious reference to the philosopher of science Ian Hacking’s important 1981 article, “Do We See Through a Microscope?” This is not the first time I’ve adapted it, as a section of my most recent book is also titled, “Do We See Through the Internet?” In those two instances the question was whether the instrument that mediates is also an instrument that delivers the thing you are trying to get at by the instrument’s mediation. With respect to ultrasound, however, the question seems naturally to pose itself with the principal stress on the word “through”, and on its peculiar double meaning.

Do we gain access to a particular sort of being that previously lay hidden from us, when we look at an ultrasound of a foetus? That is, is the foetus “delivered” already in the image of it, brought into the human realm in a way that makes it at least difficult to send it back afterwards to the realm of the merely pre-human? Or, rather, do we “see through” the ultrasound in the sense of “seeing right through” it, past the being some people take it to disclose, and into our own future lives, the continuation of our autobiographies, with or without it? That there are these two “ways of seeing”, these two understandings of “through”, seems to me to reveal something crucial about the fault-lines of the controversy over abortion.

—

Comments are open. Have at it!

Do you like what you are reading? Please consider subscribing. Paid subscribers get a new essay delivered by e-mail each week (or each two weeks, depending on my other commitments), and full access to the archives going back to August, 2020.

Soon I will make commenting an option only for subscribers. So if you like to comment, that’s another strong incentive to subscribe.

I learned a lot from this column, for which I thank you--first about the role of the ultrasound and technology in pregnancy generally, and second about the fact that no matter how we try to make comparisons of pregnancy and fetuses to other parts of human existence, a fetus is sui generis.

Everything to do with pregnancy brings up the political issue of rights versus obligations. Western societies have devolved into millions endlessly bruiting about their "rights," with hardly anyone seriously discussion what, if any, obligations they have. Nowhere does this show up more than in arguments over abortion.

Once a society untethers rights from obligations, as we have been doing ever since Machiavelli shoved morals out the door, rights have been devolving into sheer power struggles. In the old days, rights and obligations came tethered, and since a fetus could obviously have no obligations, it followed that it had no rights. Only with the rise of rights do we see the claim that a fetus has rights bubble up.

Even so, everyone has always recognized that a mother has obligations to a fetus (not necessarily to give her life for it, but some sort of moral consideration for its existence). Today, we're in a serious moral quagmire because abortion brings to the fore two irreconcilable claims to rights--the woman and the fetus--coupled with a society that shows no interest in obligations it might have to that potential child.

Except, that is, when it comes to abortion, where a huge swath of conservative Christians and others claim that women have obligations but no rights.

Permitting women to make the decision of whether to carry a pregnancy to term is the most just way to go forward. It still leaves the moral element in play, for it leaves with pregnant women what to do with what they actually alone face: Both an obligation and their rights tethered together.

Anything else is just more Machiavelli--i.e., permitting the State to have even more power over individuals.

The question of what makes a being or thing a person cannot be answered by pointing to our decision to care for that being or thing. Decisions are themselves rational responses, and so the puzzle simply reasserts itself: how ought we to circumscribe the domain of things worthy of being cared for? Moreover, if we agree that personhood is just not the sort of thing that can be read off of a brain or nervous system, we also ought to agree that personhood is not the sort of thing that can be read off of a cultural practice; surely, the latter view is just as crass and reductive as the former.