I just wrote a review for the New Statesman of Aleks Krotoski’s excellent new book, The Immortalists: The Death of Death and the Race for Eternal Life. This coming Wednesday, October 22, I am giving a talk in the “Neuroscience, AI, and Society” series at the University of Washington on several interconnected problems pertaining to consciousness-uploading, the moral dimensions of personhood, Locke’s theory of personal identity, Parfitian thought-experiments with teletransporters, and so on. Read the review when it comes out, and come to my talk if you are in Seattle. Otherwise, what follows here conveys at least some idea of the yield of my reflexions in these other settings.

Your support of The Hinternet means the world to me and to my collaborators. Won’t you please upgrade to a paid subscription? —JSR

1.

Spinoza’s always a safe bet. Everybody loves him. The other day I gave a talk to the members of a psychedelic “church” in California, with its own ordained ministers and tax-exempt status and everything. Naturally, with such a crowd, “Buddhism” and “shamanism” are guaranteed to play well. What struck me this time, though I’ve seen it before and really should not be surprised anymore, is the way the crowd likewise perks up when it hears mention of the author of the Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Fashion (1677). You can insist all you want that it’s really more David Hume who, with his “bundle of properties” theory of the self, was giving voice to a distant European echo of the Theravāda doctrine of anattā, according to which reality consists of momentary events or dharmas, while “self” is only a convenient designation for a given stream or substream of these events. Keep insisting, you simply are not going to convince the psychedelic churchgoers to get into David Hume.

Yet not all of Spinoza’s commitments seem particularly well tailored to excite the imagination. How for example does he account for the common phenomenon whereby an individual entity remains the same entity from one moment to the next? The individual will preserve its nature, he says, so long as “the same ratio of motion and rest is preserved” (Ethics Part 2, Lemma 3). I can get up and cross the room without my glasses, if I wish; it’s a lot harder to leave behind my hands, or my head. These are only differences of degree, rather than of substance (that’s because we are not substances at all, but modes), yet that is already enough for them to help us to keep track of the dazzling display of our sensations: there goes an entity, there goes another one.

Now ordinarily the death of the body would mark a stark turning point — the cessation of what had previously been a rather fluid moving-together, and resting-together, of all the relevant parts. But it is no secret that many human cultures have devised elaborate methods for keeping the bodies of at least some of their members, especially the most important ones, at least in a continuous proportion of rest, if no longer of motion. Nor have such practices escaped criticism. Sir Thomas Browne was so impressed with the lost Anglo-Saxon art of cremation, upon discovery of some ash-bearing urns at Norfolk, that he wrote his Hydriotaphia (1658) calling for the return of this old practice. It is un-Christian, he argued, to “extend our memories by monuments”. It is also futile: “Gravestones tell truth scarce forty years.”

In the early 19th century Jeremy Bentham, a very different sort of thinker, managed to convince himself that recent innovations in the chemistry of embalming might soon make it possible for each of us to maintain “the same proportion of rest”, to remain present and visible indefinitely, at least as bodies, and even to continue to attend faculty meetings in that capacity. Thus Bentham would write in his Auto-Icon of 1832 that “[i]f, by means of the improvements of chemistry and the progress of the arts, the preservation of the dead body can be so far effected as to render it incorruptible, then every man may be his own statue.”

Somewhere between learning to say “defeasible” and being made to watch the Monty Python skit with Plato and Aristotle playing football against Kant and Schopenhauer, every initiate to the guild of the philosophers will also be informed that Bentham indeed got his auto-icon, that it is on permanent display at University College London, that well into the 20th century his colleagues continued to roll him out for faculty meetings, but, tragically, that the head could not be prevented from rotting so they replaced it with a wax one and left the real one, or the parts previously composing it, to pass through their own very different succession of proportions of motion and rest.

I want to make my first bold claim already, before the reader will have much of an idea of what is going on. I want to say, namely, that the shift in attitude, from Browne to Bentham, represents the culmination of an initial phase of the modern process of privatization of the self, of transformation of the self into, so to speak, a self-referential monument, which, the hope is now held out, may be purchased and kept in perpetuity by ordinary citizens, rather than remaining only within the reach of the pharaohs. In this early phase, corresponding to a historical period characterized by widespread intellectual flirtation with materialism, even if the self is not quite reducible to the body that hosts it, the enduring integrity of the body can at least appear to carry something of the self beyond death.

My bold claim, anyhow, is that Bentham’s pickled carcass really only represents the first phase of an ongoing process — one in which we learn entirely to ignore Browne’s reserves about vainglory, and push ever further into the non-material dimensions of our personhood, in the hope that we might include these dimensions in our own auto-icons: our own use of new technologies to secure for ourselves an exemption, real or apparent, from death.

2.

We do not have to wait for the modern period to identify numerous cultural practices around the world focused on retaining at least some of the spiritual features of selves. Pharaohs had their bodies preserved, but a much more common fate for the common dead throughout the world has been to find their spirits trapped in ritual objects. For a Sakha person of Northeastern Siberia, it is not unusual upon death to end up inside a tüktüïe, a small wooden chest, made of wood and hide, which may then be sung to, symbolically given food and drink, and repeatedly fumigated with tobacco smoke (one of the many remarkable things about smoke is that it is always literal and symbolic at the same time). The actual individual self, the kut or spirit of the person, is thought to be perfectly present inside the box, even if there is no expectation that it will be able to interact as before, and even if the body that once served at its vehicle has by now entered along a very different path of motion and rest.

Around the world what we find more often is some combination of a person’s mortal physical remains with an object that serves at least some of the symbolic function of the tüktüïe. In much of the Orthodox Christian world it is common to pour out libations onto a loved one’s grave, to feed and to give them to drink. Throughout the Balkans gravestones do not just tell you who the person beneath them was; they often engage in ongoing, sometimes jocular, present-tense, second-person-familiar communication with those who come to visit them. I have seen, in Romanian, Serbian, and Albanian, the common Latin-derived inscription, Eram quod es, eris quod sum (“I was like you, you’ll be like me”). Many inhabitants of the Balkans have their tombstones and grave plots ready to go well before death; they visit the plot regularly, as if getting ready to move in, familiarizing themselves with their new digs. Death is conceptualized as a major change, but not as the cessation of all change.

In the modern West —the same part of the world that gave us signatures on oil paintings, and intellectual-property law—, gravestones are sometimes used to express some pithy idea that is thought, by the deceased or by their loved ones, to sum up the moral character or essential condition of that person. Thus Robert Frost’s gravestone, inscribed in 1963, reads: “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.” This might only be one sentence — but what if a person in fact had a single sentence that, to their own satisfaction, expressed everything about them in virtue of which they are the self that they are? If that sentence were to be inscribed on their tombstone, could it not in fact be said to bear their selfhood into the future indefinitely (or at least more than forty years, if kept out of inclement weather)?

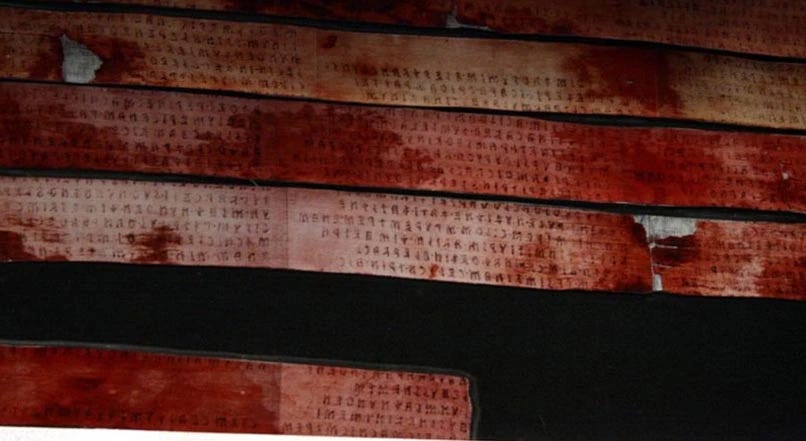

Or let us consider the case of the Etruscan mummy. We do not yet know the full meaning of the Etruscan-language texts on the insides of the bandages of the specimen brought back from Alexandria to Croatia in the 1850s by the collector Mihajlo Barić. These bandages, unwrapped, are now described as a book, the Liber linteus zagrebiensis, originally composed around 250 BCE, and consisting mostly of information about the ritual calendar of traditional Etruscan religion.

An aside: it is something like a “ritual calendar”, or a graphic rendering of the dates, times, features of the night sky and of the terrestrial landscape, constituting an individual man’s life, that seems to be the basis of tattooing practices in Polynesia and throughout much of the non-Western world. As Simon Schaffer relates in a remarkable article, when in 1792 a British astronomer greeted a Polynesian chief who had come on board his vessel, and the chief saw him there with his quill and paper scribbling down what could only have been some remarkable facts about the order of the cosmos, the chief lay right down and requested that the astronomer do him the honor of adding some new tattoos to his body.

Whether the cosmography is written directly into the body, or instead wrapped around the body at the time of death, might seem like a minor detail — the difference, roughly, between the plain-looking bower bird who builds a splendid and colorful nest, or the peacock who doesn’t build much of anything, but is himself splendid. Either way, the birds get their mates. Either way, our bodies are not just bodies, but are shrouded in accrued meaning — and more meaning accrues the longer we live, and the closer we approach to death, and the more the question of who we are, as individual selves, takes on the quality of a fait accompli.

Now imagine we’re interpreting that Etruscan text wrong. Imagine it is not just a general-purpose ritual calendar, but rather a bespoke account of the singular, irreducible “life in ritual” of the person now wrapped within the text. Suppose that for that person prior to death, as for that person’s community after death, that text was understood perfectly and exhaustively to encode all the information in virtue of which that person could rightly be said to be that person.

What the text in fact looks like is this:

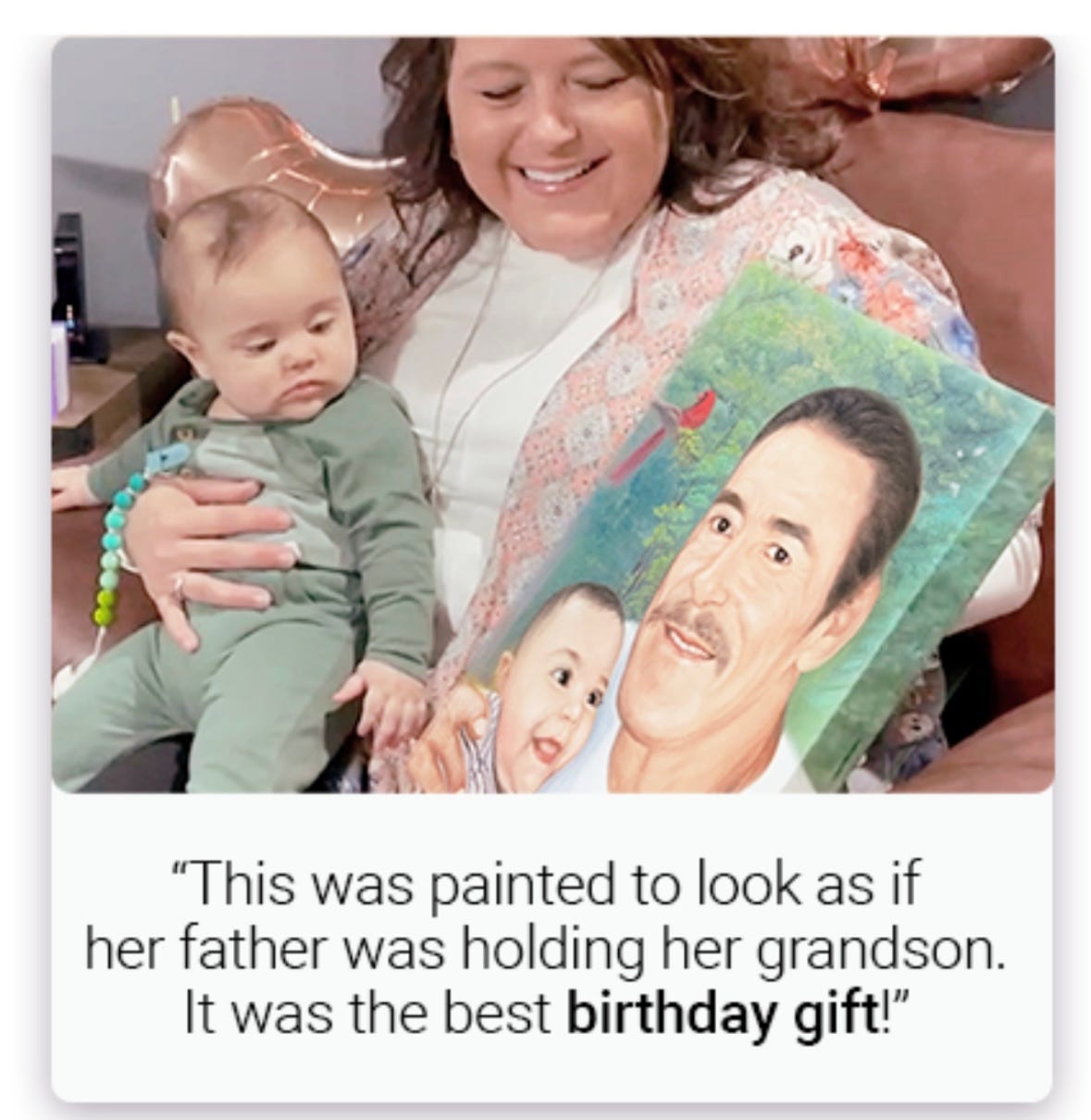

But imagine the process of encoding had been different at certain of its steps, so that the resulting text, wrapped around the body of the person whose life it perfectly and exhaustively narrates, ends up looking more like this:

Do you see now where we’re going with this? As more detail is added, and as the information-storage conventions get closer to those with which we associate our most advanced technologies, the thing preserved comes to look less like an exercise in vainglorious monument erection, and more like the transfer of a subtrate-neutral mind or spirit or self or kut of some sort from one medium to another. Presumably, if that punched-tape bandage contains enough detail, one really should be able to strip it off the mummy, run it through a specialized machine, and get right back the person the mummy had once been. But that same detailed punched-tape text could also be translated back, into ordinary natural language — Etruscan, for example.

And texts, as we know, are open to infinite interpretation. One school of interpretation, when confronted with such an exhaustive life-bandage, might come to the conclusion that all the information it contains would be more suitably expressed as a single essential truth about the person, that the entirety of the words written on Robert Frost’s unwrapped mummy-gauze, if he had had such a treatment, might be better expressed simply by the single sentence: “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.”

The promise of consciousness-uploading, as teased by philosophers such as Nick Bostrom or David Chalmers, turns out in the end to involve little more than such informational mummification as we have been considering. The auto-icon has come a long way since Bentham, but it continues to exploit the same underlying psychology of vainglory and pride, and to rely on the same metaphysical fallacy — that a monument of the self, simply by accumulating detail, could ever become the self itself.

3.

There is a fruitful ambiguity in Browne’s wording: “to extend our memories by monuments”. He almost certainly means to extend the memory of us by monuments, but not so many years after Browne’s work, John Locke, in his Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690), will lay claim to the alternative interpretation: the way to go on living is to extend our memories, in the sense of keeping on having memories. This is, I want to say, a radical break with nearly everything that had been presupposed up until that historical moment about selfhood, and about an individual mortal self’s prospects for surviving death.

“Consciousness,” Locke writes, “always accompanies thinking, and ‘tis that, that makes every one to be, what he calls self.” There is, in brief, no transtemporal continuity of identity without continuity of subjective experience, of having a perspective on the world, of being a node of perception, of vibing, of chilling. A self is an entity that consciously experiences being a self from one moment to the next, and if that experience stops, selfhood itself stops — either temporarily, as in great drunkenness, or permanently, as in death.

Locke prefers to remain non-committal about the ultimate source of consciousness, whether in the end it is the work of an immortal immaterial soul, or only of “thinking matter”, that is, matter arranged thought-wise, matter whose parts are maintained in the right proportion of motion and rest. But the ontological agnosticism only makes the practical definition of the self more radical. Among other things, it was no doubt very helpful in further marginalizing all those theories —descending from the Pythagoreans and flourishing again in the Renaissance and reflected also in enduring folk representations across likely all European cultures— of the “revolutions” of the soul, of its cycles through phases of stupor or dormancy, or through bodily forms —flowers, insects— that can hardly facilitate full-blown rational self-consciousness.

And there is another radical implication of more direct interest to our own investigations: from now on, Bentham’s false optimism notwithstanding, no cultural practice of self-monumentalization can hold out any real hope of immortality. Neither the abstraction of earthly glory, nor the magic of transfer into a ritual object such as a tüktüïe, can seem anymore like anything but a “merely” symbolic compensation. It is perhaps Woody Allen who gives clearest voice to this new predicament, when he confesses, in 1993: “I don’t want to live on in the hearts of my countrymen; I want to live on in my apartment.”

And now, finally, we have arrived at my principal thesis in the present essay. The current widespread preoccupation with self-uploading, or with other uses of technology to survive death, consistently presupposes, without argument, a Lockean definition of “self”. There can be, on this line of thinking, no immortality without enduring subjective experience of one’s self as a node of conscious perception. Anything else is survival in a merely equivocal or figurative sense. So Lockean are we all, in fact, that the previous two sentences no doubt look like plain common-sense. In fact they are pure ideology — born in the context of Early Modern English liberalism, and culminating in our own 21st-century Silicon Valley hyperliberalism.

4.

Bentham’s auto-icon, properly understood, is still just a faute-de-mieux monument to the self, one that cannot fail to remind us, ghoulishly, that the real liberal self, the one that vibes from moment to moment, is no longer there. This was simply the best one could hope for, in 1832. One way of understanding the newer tech-mediated approach to surviving death is as the echo of a broader cultural shift away from spending money on mid-sized durable goods (stereo systems, pickled effigies) and instead channeling it into subscription services (Spotify, Amazon Prime, … cloud-consciousness?). That is to say that the dream of tech-mediated immortality is very much a reflection of a much larger economic shift in the logic of status-signaling luxury consumption. Who will be the first cohort of people to have their consciousness successfully uploaded (if such a thing is in principle possible)? The people who can arrange in their wills to pay for this service indefinitely into the future.

What more perfect culmination of the history of liberalism could there be than to find the self itself transformed into a premium subscription service? The history of metaphysics and the history of political philosophy converge here with dazzling symmetry: in the 21st century it is consciousness itself that remains as the great terra nullius, for the tech companies to conquer, and for individuals to seek to win back, either individually, by paying for it (Silicon Valley’s preferred mode) or collectively, by organized resistance. Or, I suppose also, by critical engagement such as I am offering here.

But you may yet be surprised to see my parenthetical admission of agnosticism. I admit it: I honestly do not know whether consciousness-uploading is possible. I suppose at least to this extent I am Lockean. I think consciousness could well turn out to be the sort of thing that can be transferred from one substrate to another, from neurons to microchips or even, if you have enough of them, to toilet-paper rolls and rubber bands. It could also turn out to be dependent on a material substrate, yet prove to be non-transferable, in view of any number of special features of a biologically based consciousness that it took evolution hundreds of millions of years to hone. Or it could, as Descartes thought, have nothing to do with any material substrate at all. I don’t know.

I feel much more competent in reflecting on the cultural histories of the ways different people in different times and places speak of our prospects for surviving death, and here I cannot help but notice that we did not need to wait until the era of functionalism in the philosophy of mind to find people committing themselves to substrate-neutrality — there is for example the tüktüïe, or the trunk of an oak tree, into which the soul of a Druid priest might pass. Unless otherwise specified, in fact, it seems that the great majority of defenders of the substrate-neutrality thesis have been, unlike its current defenders in philosophy departments and in Silicon Valley, resolutely non-naturalistic about what makes a self a self. They have been, by and large, to use a somewhat antiquated and inexact term from comparative religion, “animists”. Whether Bostrom-style whole-brain emulation turns out to be viable or not, the wider cultural representations of what this process achieves, metaphysically, will continue to be of primarily anthropological interest, and anyone who neglects to notice the continuity of our representations with those of other cultures, whose fundamental ontology we otherwise believe we have surpassed, is really missing the interesting part.

5.

Spinoza in fact gives us more hope for immortality than whatever approximation of it might be won by holding onto a uniform proportion of motion and rest at least a while longer. He rejects endless duration after death —sitting around, vibing, in that place where otherwise, as David Byrne sings, “nothing ever happens”—, but he insists nonetheless that “the human mind cannot be absolutely destroyed with the body, but something of it remains which is eternal” (Part 5, Proposition 23). Eternity here is not duration, not anything to which it would even make any sense to think of renewing one’s subscription. It is, rather, a perfection of that part of the mind that is identical with adequate ideas, which, once achieved, shifts the nature of one’s being outside of time altogether. “We feel and experience that we are eternal,” and properly understood this eternity has nothing at all to do with infinite duration. “Nothing ever happens” turns out to be true not because Heaven is boring, but because there’s no succession of moments for it to happen in.

More recently, in his Surviving Death (2010), Mark Johnston has done a formidable job of marshaling theological language to give a naturalistic-by-default account of what immortality might yet be even without a persisting ego or temporally infinite afterlife. In his view, an ethically good person has already undergone a sort of death of the self in “agapic” identification with others. The good survive death, Johnston thinks, insofar as their patterns of concern are re-embodied by future persons. By contrast, even on the metaphysical assumptions that have sustained traditional theological accounts of the afterlife, standard accounts of personal identity cannot carry “me” beyond death in any coherent way. I would adapt this claim, in light of what I have already written, to say that standard post-Lockean accounts of personal identity cannot carry me beyond death. It is in fact precisely the mismatch between self-as-enduring-node-of-subjective-experience on the one hand, and the true meaning of any serious theological articulation of the doctrine of salvation on the other, that has led to such bleak imaginings as the Talking Heads’ “boring Heaven”, or such comic juxtapositions as Woody’s, between immortal glory and apartment life.

Beyond moral philosophy there is also considerable material for the immortalist imagination that may be drawn from recent insights in computational biology. While working with bff, a program that models the behavior of cellular automata, friend of The Hinternet Blaise Agüera y Arcas noticed the way replicating strings appeared to persist inside other replicators. At first this looked like a bug, and after meticulous debugging that is what it turned out to be… at least on a conventional evolutionary model. But something else becomes clear when the model is extended to include symbiogenesis, an evolutionary process studied by Lynn Margulis and others, in which two or more distinct organisms merge to form a single integrated one, combining their genetic or cellular structures in a lasting way. The most familiar, and most important, example of symbiogenesis is the process by which, around 1.5 billion years ago, free-living aerobic bacteria invaded, and then become integral to, all eukaryotic cells — including our own. In a world of reproduction by splitting alone, neighboring lineages compete in a zero-sum struggle for the same niche, and the dynamics favor the persistence of only one variant. The result is constant extinction—an endless Survivor scenario on every ecological island. In a symbiogenetic merger the combined organism encompasses its partners, preserving them and, at least to some extent, the environment they occupy.

One would not want to be overly facile in assimilating this section’s metaphysical, moral-philosophical, and symbiogenetic considerations to one another. Yet, taken together, Johnston’s and Agüera y Arcas’s insights might both buttress the same general and deep claim about our mortal predicament, and about possible pathways out of it — that we living beings are, as a rule and in diverse ways, always getting up inside one another. It’s what we do best. We’ve been practicing at it since we were bacteria. Now that we are human it takes on an additional moral and metaphysical significance, but it is life itself that establishes the rules through which morality may be realized and perfected.

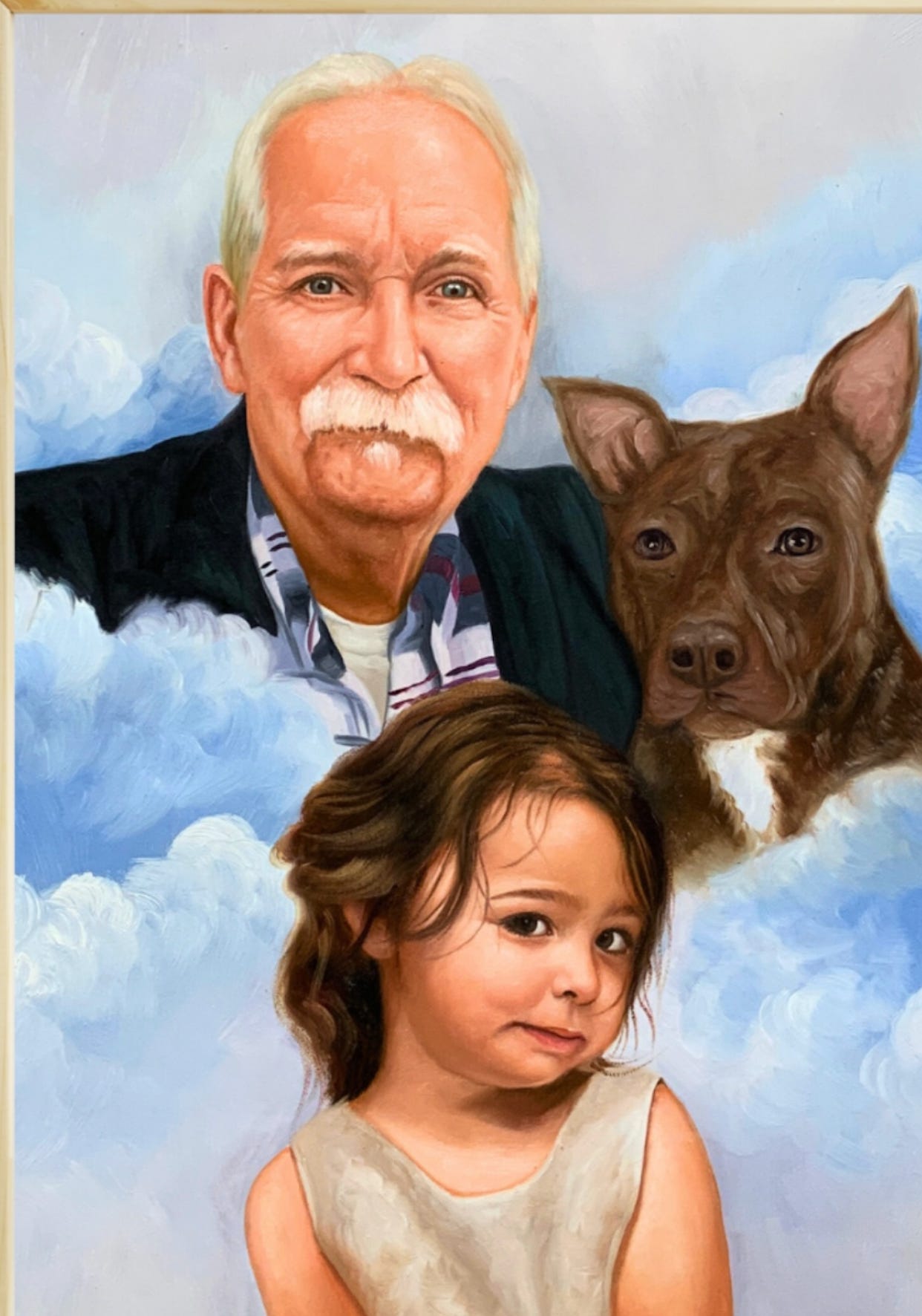

Have you ever answered the question for yourself, "Who was I before I was born?"? In more a more Zen Buddhisty way, "What was my face before my parents were born?". No need for a lot of words. Just show me.