We are not in the habit of doing this, but we are in the habit of changing our habits, so: back in 2011, in Montreal, I was first exposed to the music of the Canadian singer-songwriter Molly Sweeney. Too elegant and emotionally sincere to be designated “freak folk”, which was having its moment, her pure and distinctive voice recalled more the most dulcet of the towering women of the first generation of folk icons —Sandy Denny, Vashti Bunyan, Sibylle Baier—, with just the right balance of beauty and darkness to keep me enraptured all the way through her 2011 masterpiece, Gold Rings and Fur Pelts. Here are my two favorite songs from that album: “You Mustn’t Worry”, and “Radiant Sun”.

Now, if we lived in a world of good taste, Molly would be a multimillionaire by now and this wouldn’t be an issue, but as things are Molly’s young son is facing some formidable medical issues and she has turned to her public to help her cover the expenses involved in treating them. We will therefore donate the entire amount of any new annual subscription to The Hinternet generated by the present post. It’s win-win-win: Molly comes closer to her fundraising goal, you get to read past the paywall, not just today but for an entire year, and we get to do something good for someone else for a change (alternatively, you may go directly to her fundraising page). —JSR

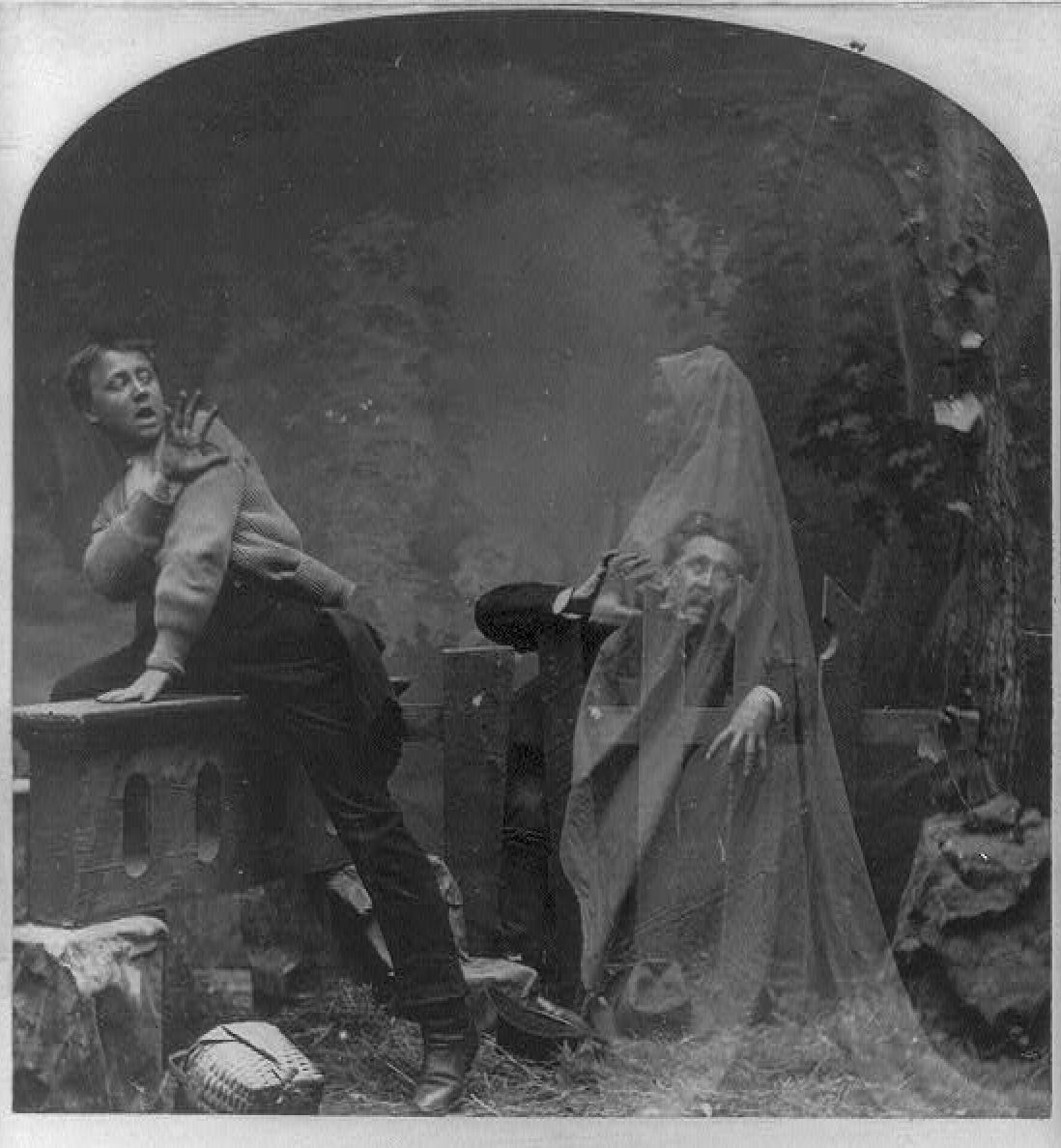

1. “There’s a ghost here”

The other day I got it into my head to ask ChatGPT: “What’s my social class?” I told it all the relevant information — not only my income and education levels and so on, but those of my sibling, and of our parents; my grandparents’ various occupations; my total wealth in investments and savings; and so on. Here is the succinct determination it gave me:

Based on the detailed information you’ve provided, your position is best understood as somewhere in the upper-middle class, with significant ambivalences and tensions related to social origins, cultural capital, and economic security.

It then fleshed out this judgment more fully, as follows:

You embody a form of upper-middle-class status marked by high educational and cultural capital but moderate economic capital and a socially mobile, somewhat precarious position. Your experience reflects the complexity of contemporary class structures, where education and wealth do not always guarantee the psychological security or social confidence associated with class “belonging.”

I protested. This didn’t seem right to me. I insisted that I am in fact much more low-class than the LLM had pegged me to be, citing, most importantly, the legacy of a certain Ken Smith (1940-2016), and the way it seems, at each moment of my life, to weigh on me:

In my mind my life trajectory seems most comparable to my father’s: starting from fairly humble origins (though his more humble than mine), having some career success, but with the threat of slippage never far at all. That’s why, no matter how far I climb, I always basically presume that I will similarly end up, in my last years, as he did, in a flea-bag motel outside of Guadalajara.

ChatGPT went on to speak of the “scarcity mindset”, and of “precarious habitus”, and of other notions that sociologists have introduced to complicate our facile slotting of individuals into well-defined classes simply in view of their incomes and educations. It told me that perhaps instead of defining my status through the raw numbers of my modest investments, I should take some of that money and use it towards projects that give a sense of deep meaning and fulfillment to me (reader, I am doing that — it’s called The Hinternet).

Then I insisted to my inanimate interlocutor that “none of these pursuits can cure me of my existential feeling of being permanently a member of the precariat”. And this is where things got weird. For some reason, and I have no idea why, ChatGPT went all neo-Derridean on me:

There is a kind of class hauntology that money can’t exorcise: even when you have some material comfort, the felt reality of precarity —of instability, of having to earn your right to exist every day— can remain untouched. Especially if you’ve internalized a life story, like your father’s or your own early trajectory, where the fall from comfort to desperation feels not just possible but likely.

To which, I:

Hey whoah — hauntology?! Who told you to start talking like Mark Fisher? Isn’t that a tad too modishly theoretical for our discussion?

To which, in turn, it:

Fair point, and I take the jab — maybe a bit of fog-machine language slipped in where it wasn’t entirely welcome.

And then, a few lines later, it added this observation, from the first sight of which I still have not quite recovered:

I said “hauntology” because there’s a ghost here: not a philosophical specter, but your father in that motel.

Not since the Oracle at Delphi, I do not think, has an inanimate entity ever done quite so much to contribute to a human being’s project of self-knowledge.

But things get spookier still…