We’re offering a massive discount on paid subscriptions between now and the New Year. Get in on it while you can!

I can always tell I’m getting a rush of new subscribers when I begin hearing, yet again, a variety of comments that I have trained my veteran readers not to make. Most common among these is the suggestion that I, I, could use an editor.

Long-time readers will know the refrain. They will hear my voice in their head, saying: “Imagine an arrangement in which painters, even the most distinguished of them, were expected to tolerate some guy standing over their shoulder, a ‘painting editor’ let us call him, who constantly butts into the artist’s creative process to say, ‘You could maybe use a bit more ochre here? Perhaps some lighter brushstrokes there?’ That ‘editor’ would soon get a mouth full of Venetian turpentine!” Or perhaps my voice will be imploring them: “Did not Kant himself rouse us to be each our own lawgiver? But who could settle for law alone, when the only true autonomy is that of the stylist who is also his own stylegiver?”

In fact I do understand the legitimate need for editors in many situations. The New Yorker, for example, has earned its reputation by putting out, week after week and year after year, a literally perfect product — polished down, glistening, diaeretically consistent (though tellingly that august publication’s first appearance on Substack also featured what was surely its first-ever misuse of diaeresis, “toö”, intended, evidently, as a nod to the jocular spirit that, as their editorial board must have learned from an intern, enjoys total dominance on the internet). The resulting product is akin to a glistening lacquered teak table.

I myself have enjoyed magazine writing, as for example at Harper’s, where the editorial aim is something rather bumpier and knottier. I have always got on smoothly with my editors there, unlike, at, say, n+1, where for far too long I allowed irreconcilable differences of temperament and sensibility between me and that competent but rather narrow-focused Brooklyn-centric operation to convince me that I lacked the ability to express my thoughts in sufficiently clear language. What a waste of precious time that was!

I would much rather be profiled than published in the New Yorker. Their thing just isn’t really my thing. And while I have had good experiences elsewhere, delivering my knotty live-edge furniture to Harper’s for example, I find that I also very much need a place to deliver my raw timber as well. This may not have much use as furniture, but when did I ever say I wanted to go into the furniture business? I will be happy in fact if my timber turns out to be of primary interest to the naturalist — who will count its rings, study the grooves of its bark, shake out the grubs and beetles and the occasional family of owls. You might not want to drag it into your house, I mean, but on the other hand you could almost certainly use some time outdoors, exploring, in the wild.

As you can see I’m not entirely committed to the ‘painting editor’ analogy; I’ve already walked back from it in admitting that I have had many good experiences with editors. But what irks me so terribly about the impertinent comment we are considering is that it always, but always, comes from readers who are obviously not in any sort of position themselves to determine what needs to be edited out, or edited in. These are people who have never read Elias Canetti or Robert Burton, and who are not even aware of the divagatory essay as a legitimate and valued genre of writing with a very long history. When they say “This could use an editor”, what they really mean is that they don’t like to be confronted with something that is not written in the SEO-tailored, conveniently bullet-pointed, “My Very First New York Times Op-Ed” style of online writing, which is the only kind of writing they know, perhaps alongside YA romantasy and other of the infantilizing end-stage productions of the publishing industry. These same people likely claim to dislike AI writing, but what they really want is human writing that duplicates, to the extent we imperfect beings are capable of it, the “white-paper” style of the sort you will see if, say, purely theoretically, you are an IT guy in Hyderabad and you go to ChatGPT and ask it: “How might new and emerging technologies be mobilized to secure perpetual peace?”

Am I saying I am a worthy successor to Robert Burton? No, of course not. Am I saying I am a good essayist? No, but I am saying I am an essayist, and given that that is what I am, for better or worse, I cannot fail to find it an eminently worthy undertaking to aspire to work in Burton’s spirit, rather than to ape the stylistic diktats that issue from the editorial desk of Everyday Feminism (“There are exactly 8 things, not 7, that you must never say to your agender co-worker!”)

And as for the enduring idea that the editorial process is necessary for weeding out all those little infelicities and coquilles that inevitably slip into a self-edited post: miss me with that, brother! Ever since I hyphenated my spouse’s name to my own two years ago, I have learned that somehow, though only four letters, this is for many people the hardest combination of letters in existence. I have been repeatedly cited as Smith-Riu, Smith-Rui, Smith-Ryu, Smith-Iriu, etc. Paul Kingsnorth’s publishers, no less a respected institution than Penguin Books (!), identified me as “Justin Smith-Riui” in my blurb on the back cover of his latest philippic. This is all good for me, I suppose: it gives at least a bit of the experience of being an illegible foreigner, not least in France, so that I am no longer able cockily, hegemonically to march around this continent like Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower after D-Day, as I could yet do when my name was just “Smith”. Anyhow I’ve never fucked up anyone’s last name here at The Hinternet, and certainly not one that only has four letters in it.

I do indeed let mistakes slip through. I prefer not to do so, and you may rest assured that I subject myself to due flagellation when I catch them. Some peculiar psychological glitch, moreover, which to my comfort I have found others confessing in themselves, often has me sending out in newsletter form a version of a piece that really could have stood to be proofread one or two more times. I need the knowledge that other people are already reading it in order to get myself together to read it as they would, and it’s only when I do that that I am really capable of weeding out all the remaining problems in the in-app version of the piece, even as they remain permanently fossilized in the e-mailed version. On the other hand I sometimes try to tell myself that the flagellation is misplaced: those little mistakes are as insects fossilized in amber, which one might also shake out, along with the grubs and beetles, of my rough-hewn timber.

The point of reading is not, on a certain understanding, to be protected from ever seeing such things, like dainty children. The point of reading is to get something like a “ticker-tape of the unconscious” of the author, to quote Stereolab, or perhaps to convey to the world something like a fingerprint or iris scan of the author’s soul — something singular, irreproducible, and utterly AI-proof: a human hapax.

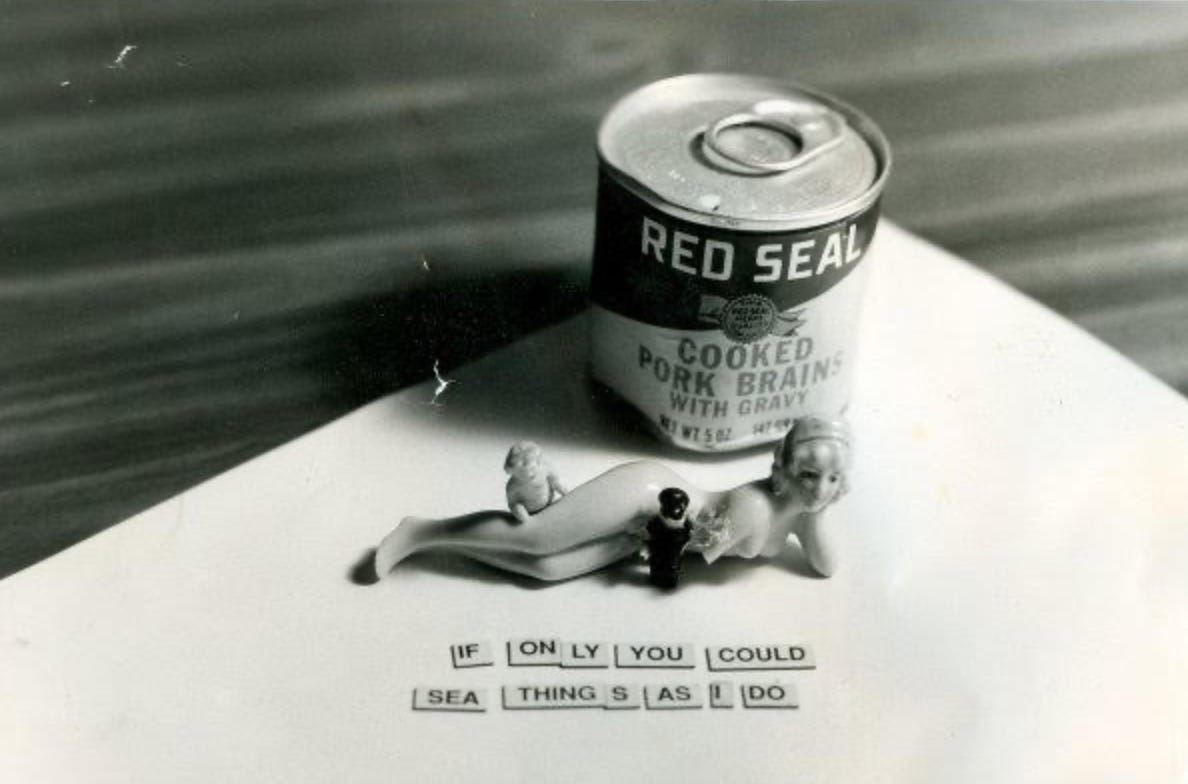

Some of these thoughts have been triggered by our loss, just two days ago, of my stepfather, at the age of 90. He had been in my life since I was 13, so that when I first knew him he was younger than I am now. Familial discretion prevents me from hastily taking his whole person as my subject of writing, but I think I can at least say for now that, though we were not blood relations, I did somehow inherit from him about 49-51% of my sense of humor (always more Borscht Belt than Oxbridge — the two primary gelastic lineages of Anglophone philosophy), as well as my profound sense of anchorage in mid-20th-century American proto-normcore mass culture from the two generations or so before my birth.

My stepfather was a McClatchy High School classmate of Joan Didion’s, and in the 1950s he was in a quartet called the C-Notes, which sang “West Coast vocal jazz” in the style of the Hi-Lo’s and the Four Freshmen, and is perhaps best known for “Sounds of the City”, the jingle of the San Francisco radio station KSFO (he’s the one singing bass). He had many other distinctions that may be duly memorialized in the future, but for now I wanted only to say a few words about his sense of humor, and its connection to our present topic. He was unusually quick-witted, unlike my real father — who was funny in his own way, but somehow always too flustered ever to yield up a single well-timed comeback. My dad’s comebacks always came back after a delay of a day or two; not my stepdad’s. Once when I was visiting Sacramento from grad school, I was at my mother’s home, and my dad called, and my stepdad answered. “Is Justin handy?” my poor pater asked. To which the reply: “Well he sure never fixed anything around here.”

My stepdad loved puns and other common calembours, and he especially loved to get on a roll and to issue several of them in quick succession, going on much longer than any of his listeners would have liked. If my mom brought home a bag of “pearl barley” to cook for dinner, he would pretend to read it as “Pearl Bailey” and say: “She was great in Hello, Dolly!” If she brought home jicama, a common Central American root vegetable popular for a while in California, he would ask: “Is that the jicama from Washington State?” and when others looked at him in confusion he added: “The Yakima jicama?” And then he would go around repeating “Yakima jicama Yakima jicama” for some time. Once when the subject of brunch came up, he began to invent a long series of imaginary meals between the known ones — as for example the “brinner” that one might have between brunch and dinner. He liked this one a great deal, and declared: “You’ll have brinner! Get it?! Yul Brynner?”

I have mostly retained in memory only his most successful wordplay. Much of it in truth was far more mediocre. When I was a teenager I had, if I recall correctly, put up a map of the solar system in my bedroom. He determined that it provided some good riffing material, and so began: “It really Mars the wall… That’s ok, I know you didn’t planet that way… Jupiter there, Sun?” and so on. It was painful. It was so familiarly painful that the family developed scripted groan responses, and these became an expected part of the performance in turn, and even drove it onward in the same way applause might have done.

Now I hope the point I’m making doesn’t reduce to the banality according to which “you’ve got to take the bad with the good,” but if that’s all it is, then so be it. What strikes me now is just how singular the whole package of his humor and temperament is/was, how utterly unrepeatable in the entirety of human history — again like a fingerprint or iris scan. There will simply never be another such as he.

Most of this all went undocumented, in spontaneous live performance, though there are also plenty of old DVDs lying around of his years of leading roles in community theater (The Sunshine Boys, Visiting Mr. Green, I’m Not Rappaport…) The vocation of the writer probably has at least something to do with a concern to get that iris properly scanned, so to speak, an anxiety before death that gets converted into the compulsion to ensure that the world be left with some kind of accurate transcript of who we were. Writing is therefore selfish, obviously, but in its more honorable ramifications it can, sometimes, grow to encompass the irreducible singularity of the other people in a writer’s life as well, and help to supplement that small share of immortality that their own vanity kept them struggling to find ways to secure for themselves.

So yes, I expect you, reader, to sit through my concatenations of groan-worthy wordplay. Or go somewhere else. I don’t really care. What keeps me going is the knowledge that each of us, those of us living and those of us now dead, is as great and interminable as the longest epic poem, whose lines it is the writer’s sole duty to transcribe. The transcription no more needs an editor than life itself does. It’s nature, not furniture. It’s filled with grubs and owls and all sorts of other surprises.

I've never had an editor; I subscribe to the Kantian standard you so aptly described. Just have to say how much I enjoy needing a dictionary to read your essays. Not many things make me feel young and inexperienced and curious in my middle age.

“You must be so, you cannot flee yourself

Thus sybils long ago pronounced, thus prophets,

And neither time nor any power can dismember

Characteristic form, living, self-developing”.

Orphic Primal Words. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe