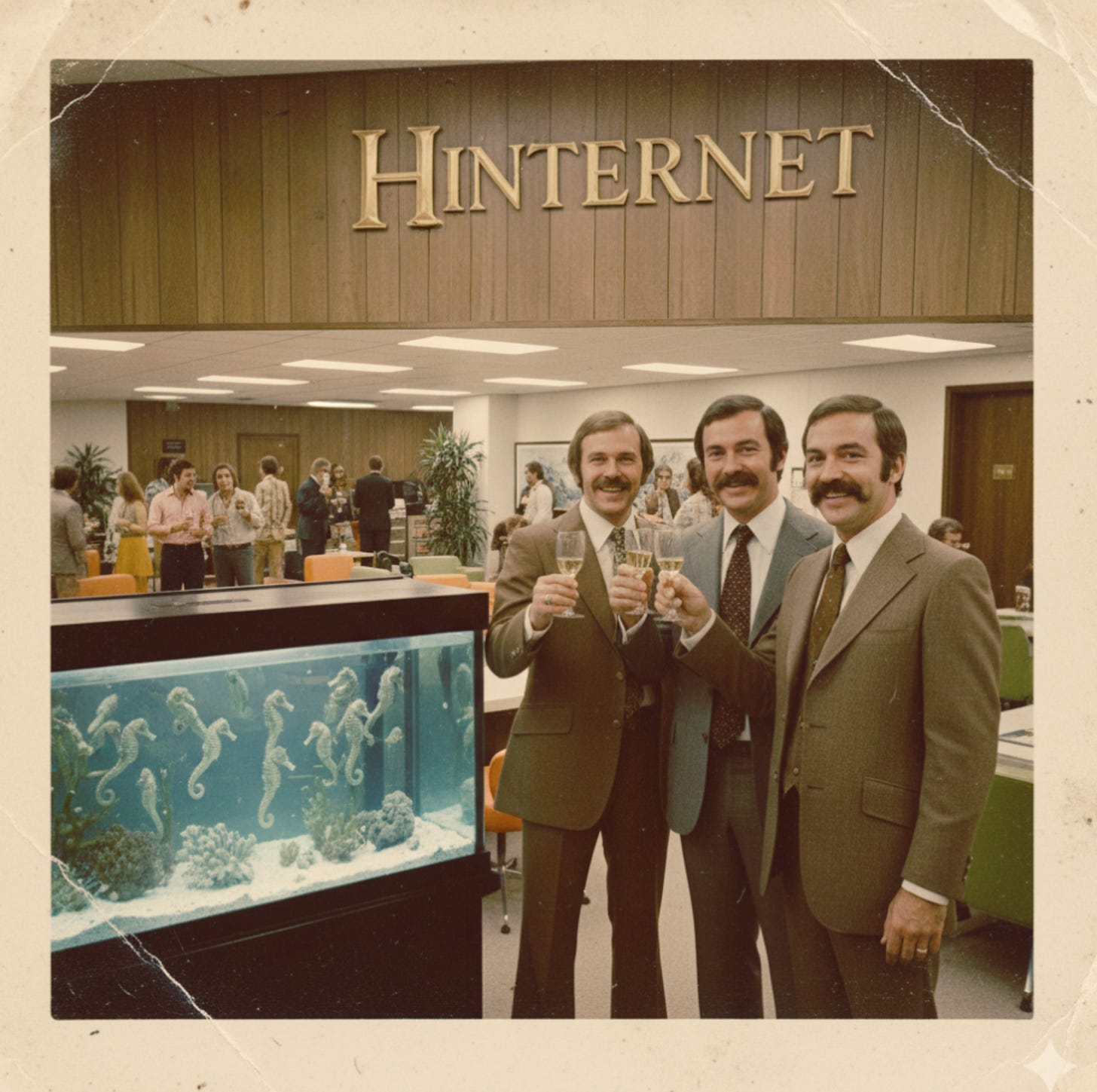

Celebrating 110 Years of The Hinternet!

From Leland Junius Wheat’s Cortico-Mimetic Association Engine to the Sempitern Series-7 JSR

In a September 7 missive, our Founding Editor expressed his pride at having reached, so he said, the fifth (!) anniversary of The Hinternet, which he described as “a Substack-based publication founded in September, 2020”. In so doing he knowingly went against our explicit request to him, to use the occasion of this anniversary post of his to set the record straight, and to tell the full story of The Hinternet’s long pre-Substack history.

Admittedly, until not long ago the “Founded 2020” bit was part of our official editorial line. You may find this dishonest, but if so we invite you to ask yourself honestly whether there has ever been a history-making publication whose editorial line was not, at least in part, built on a noble lie. And we would have gone on maintaining our noble lie indefinitely, had our former “On Language” columnist, Edwin-Rainer Grebe, not betrayed our secret, stealing a cache of top-secret photographs from one of the strictly off-limits lower strata of the “Nest”. This gross betrayal brought Edwin-Rainer an attractive cash payout from Das Bild, the rabble-rousing German tabloid. But rather than allowing that unscrupulous rag to dishonor us, we decided to get out ahead of things, to preempt their scoop, and to tell you, ourselves, the full story of The Hinternet’s founding in 1915.

Regular readers will already be familiar with the above-mentioned “Nest”, a term we sometimes use to describe not so much the physical or spatial, as the metaphysical and conceptual, structure of The Hinternet’s operations. There is, recall, the upper layer at which our featured columnists and our interns typically dwell. And just below them there is the layer where we find Olivia and David sharing a closet-sized fluorescent-lighted office. Then comes the layer where Hélène Le Goff sits in her richly appointed suites. Deeper still we find JSR (the character), then JSR (the moral person), then Justin E. Smith (the legal person). Deeper still than that —and we understand this is hard to believe—, there is the Sempitern Series-7 JS-Robot, who, if our engineers are to be believed, will carry the aforementioned moral person into the future indefinitely, or at least until the heat-death of the universe.

There are only two layers of the Nest that lie even deeper. The one beneath the Sempitern is inhabited entirely by the race of “Storytellers”, who as you may recall are neither fictional characters, nor human beings, nor “AIs” (😂), but rather eternal entities who share at least partially in the nature of what used to be called “angels”. And the level beneath them —here of course we mean “beneath” not in the sense of an inferior position in a hierarchy, but on the contrary in the sense of being more fundamental and more fully imbued with what once would have been described as “formal being”— is inhabited by the one whose name, you will understand, we are strictly prohibited by tradition and taboo from using.

Much of this has been revealed on at least one previous occasion. What we did not reveal at that time, but are effectively cornered into addressing now in the wake of Edwin-Rainer’s wicked treason, is how the Nest came to be in the first place. Who built it, and why? What is the “deep history” of The Hinternet?1

You might not be too surprised to find out that this history is deeply intertwined with the history of Riverbank Laboratories, the private institution founded by “Colonel” George Fabyan (1867-1936) in the suburbs of Chicago in 1916, with the sole stated purpose of pursuing research into its founder’s own singular preoccupations. Among these, notably, were the theory that Francis Bacon had been the true author of the works of Shakespeare —which Fabyan believed could be proven by cryptographic analysis of the texts—, as well as the idea that certain grain crops could be much improved by attention to the influence on their rhythms of growth of different phases of the lunar cycle. As early as 1913 the eccentric financier sought to hire the physicist and acoustician Wallace Clement Sabine (1868-1919), to build for him an acoustic levitating machine that he believed had been described —in enciphered form, of course— by Bacon himself. We are halfway, here, between New Atlantis and Boston Dynamics, between Elizabethan obscurantism and corporate R&D initiatives in the service of American power.

By 1917 Riverbank had mostly bracketed the belle-lettristic projects for which it had been founded in order to lend its significant cryptographic expertise to the war effort. Its contributions to American military intelligence over the next two years were significant, and can plausibly be seen as having provided a template for the public-private military-industrial complex to come.

That same year Fabyan acquired a company that had been founded in Milwaukee two years prior, and that had previously gone under the name either of “Hen Rite Ten”, or of “Tenth Rite H” — the one said to have been a battery egg farm, the other an esoteric reference to some rank or chevron within the leadership of Noble Drew Ali’s Moorish Science Temple. Either way, whether it was a Moorish temple or an egg farm, what it in fact was was a front for an organization dedicated, in the words of its founder Leland Junius Wheat (c. 1841-1926), to “sustained investigation of the nature, causes and principles of the narrative art, and of its potential for enhancement by modern calculating machinery”. Upon its fusion with Riverbank, Wheat’s operation was restyled “The Hinter-net”.

Little is known of the early life of Leland Junius Wheat. We may at least say with certainty that, while Fabyan’s “Colonel” was but an honorary designation, Wheat was in fact a Colonel, having risen to that rank by 1864 as a young officer in charge of the Union Army’s fledgling aeronautics unit. It is reported that at the Battle of Nashville in December of that year he deployed a fleet of hydrogen balloons outfitted with timer-set cameras to bring back photographic reports of troop movements behind enemy lines.

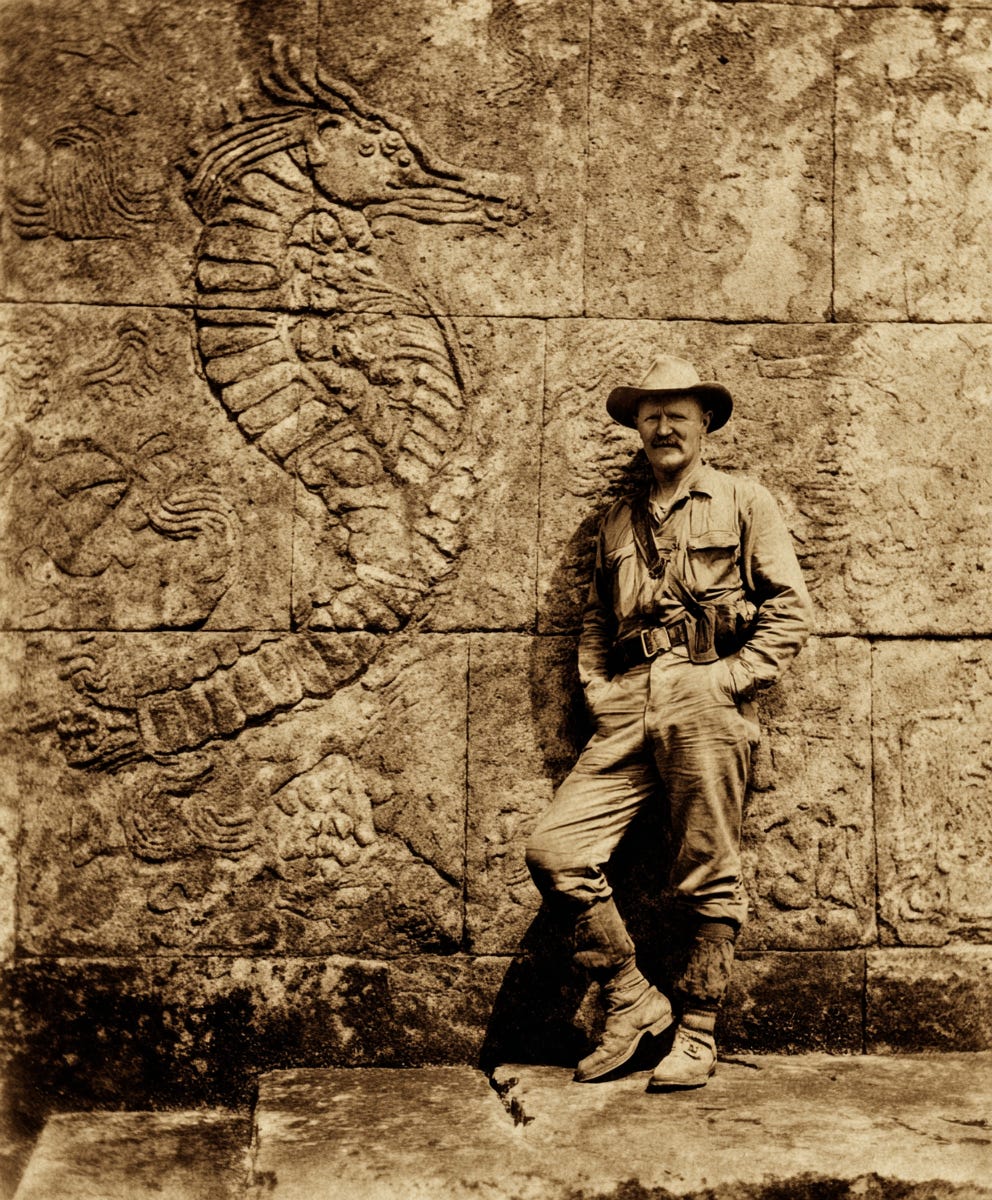

We have next to no information regarding Wheat’s motions and projects between the end of the Civil War and his reappearance, at a rather advanced age, in Milwaukee in 1915, other than that over the course of the 1880s he had grown deeply preoccupied with the artistic motif of the seahorse across cultures and historical epochs. This interest sent him on a tour of the world, to far flung destinations from Guatemala to Pompeii, ultimately yielding an obscure academic monograph, in German, entitled Das Seepferd als Symboltier. Eine ikonographische Studie (1889). Later in life Wheat proved consistently taciturn when asked about his seahorse research, and as an explanation for why these creatures had interested him so much he only muttered, as if it were self-evident, that this is the only species that features “pregnant males” (technically untrue, but not by much).

A brief appearance in French Equatorial Guinea in 1903 has our man Wheat studying the practice of couvade among the Fang people (see footnote 14 to Henri Trilles’ Quinze années au Congo français, Paris, 1905).

Other than these scant traces, Wheat remains a historical cipher.

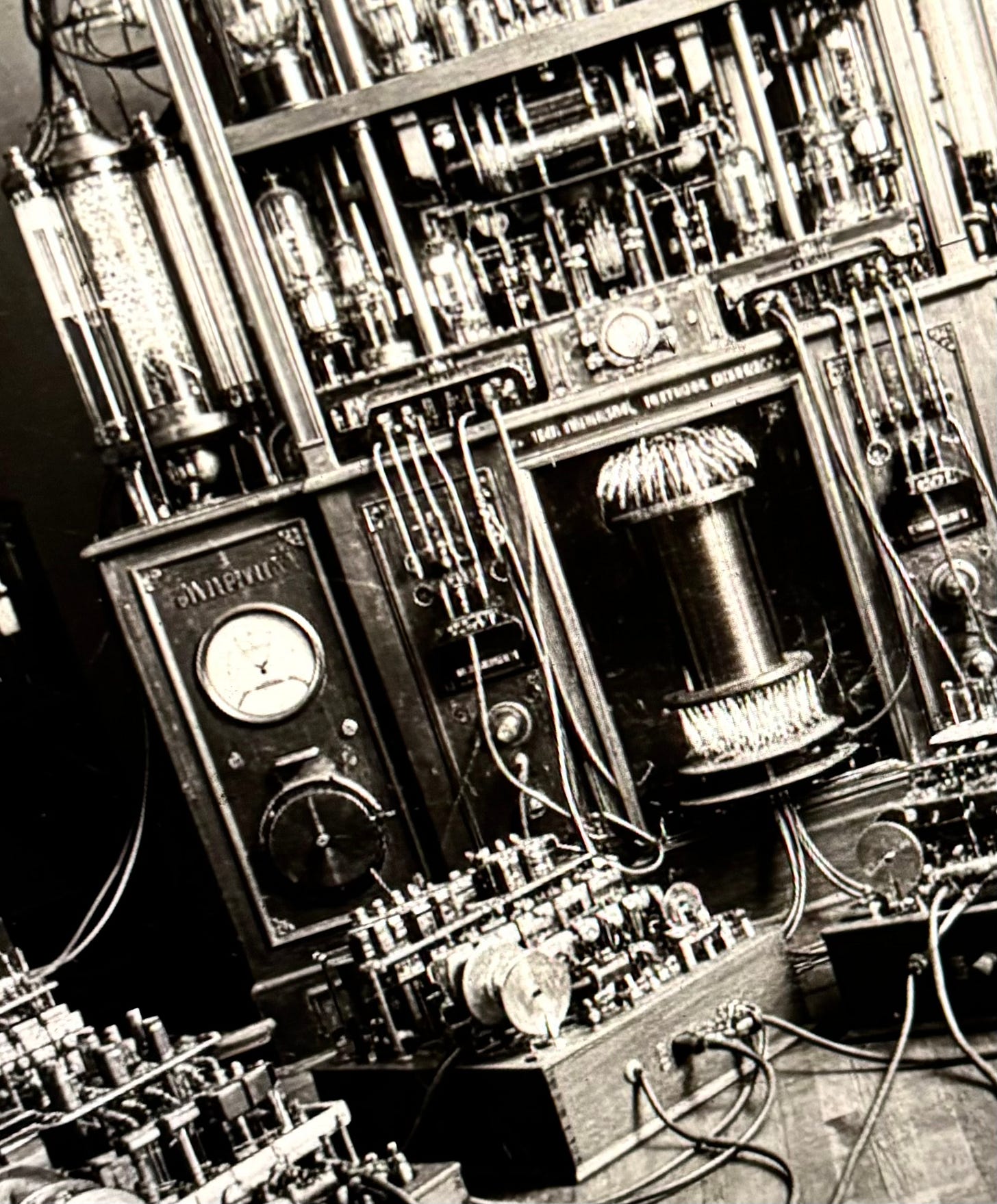

It does not take long for news to spread from Milwaukee to Chicago, nor should we be surprised to learn that Wheat’s work was of interest to Fabyan. For it seems that by 1916 Wheat —assisted by an unnamed Breton woman with uncanny mathematical ability— had built a working model of what he called his “Cortico-Mimetic Association Engine”. This device was constructed on the proven principles of the telephone exchange and the relay register. In it, vast arrays of electromagnetic relays, each capable of acting both as receiver and transmitter, were wired in layered banks in such a way that triggering one of its circuits propagated a signal to several others with varying degrees of force. This in turn facilitated an approximate imitation of the nervous paths described by the physiologists who study the human brain, whereby the repeated passage of an impulse renders its pathway more active. Input was supplied, according to Hinternet researchers’ later efforts at reconstruction, by punched-tape patterns passed through telegraphic keys, and output by incandescent bulbs and some kind of ticker-tape providing a visible record of the Engine’s “associations”. By the adjustment of resistances and relay thresholds, it is believed that the device could “form habits”, so that with repetition it might more readily summon the same patterns in response to a given input, somewhat in the manner of conscious thought and memory in human beings.

It seems that while Wheat had been primarily concerned to use the machine for generating entirely new and original narrative literature, Fabyan mostly understood its potentials through the lens of his older preoccupations. He hoped to acquire The Hinter-net, in particular, in order to apply its Association Engine’s reckoning power to his collection of obscure Elizabethan esoterica, and thereby to tease out from these texts all the hidden acrostics, backwards messages, and other signs of their true authorship as might be discovered.

These differing priorities hardly mattered in the earliest period of the two entities’ fusion, as by October, 1916, the US government had anyhow requisitioned the Association Engine for the war effort. We know very little about its precise applications in that era, other than that it seems to have been involved in British intelligence’s deciphering of the telegram sent by German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to his country’s embassy in Mexico, in January, 1917, seeking to draw that country into war against the United States. “We now have Fabyan’s ‘Big Brain’ installed in Room 40,” Sir Reginald Hall of the British Admiralty wrote in his private journal earlier that month. “It seems to have been slightly damaged in its transport across the ocean, but it can still work wonders undreamt of by our human codebreakers.”

The fate of the “Big Brain” for several years after the Treaty of Versailles is mostly unknown. We can at least say with certainty that it was never returned to the US. It is also known that Fabyan himself paid a visit to London in early 1921 to seek to reclaim “his” property from the Admiralty. For unknown reasons US officials had by the end of the war sought to distance themselves from the Engine, going so far as to deny any knowledge of it. The UK by contrast seems to have assumed possession of it as part of the spoils of war, though Fabyan did manage to negotiate an arrangement whereby he had access to the device, still housed in the legendary Room 40 that had been the nerve-center of British wartime cryptography, Monday to Friday from 10pm to 5am and all day on weekends, to pursue whatever research projects he deemed important. It was also during this London sojourn that Fabyan made the acquaintance of Wilfrid Voynich, who by this time in his life was primarily based in New York, but still made frequent trips to London for his antiquarian business. The two of them appear to have devoted a significant portion of their nocturnal reckoning sessions to the (utterly unsuccessful) decipherment of the latter’s eponymous manuscript.

Wheat himself, who died in March, 1926, was already too elderly to travel across the ocean. But this is not to say he entirely abandoned his claim to the device he had worked so hard to build. A single letter, dated June 18, 1923, addressed to a recipient known only as “la Bretonne”, has recently been discovered in the archives of the Chamber of Commerce of the city of Nantes.2 This document brings us at least some way towards understanding the subsequent fate of the device. He writes, in part:

I have complete faith in your ability, ma chère, to win our Engine back from Fabyan, and to end once and for all its wasteful application to his trivial acrostics and word-searches. That’s not what I built it for! The Engine is not for studying old stories, not even the most enigmatic ones, but for generating new ones. You go to London, ma biche, you get an audience with Major General Harrington at the War Office and you work your magic on him. Cast a spell if you have to, though that probably won’t be necessary. They already know they’re fooling around with dark forces. They’re probably looking for some way to wash their hands of it, just like the Americans did.

You understand what the Engine is — don’t you, ma douce? It runs on mechanical principles but it is no mere mechanism. I believe with every fiber of my being that if its energy is sufficiently focused, for a sufficiently long period of time, the device will succeed in breaking through to what I think of as “the lower layers”, where it will come into contact with the minds that reside there, and begin to yield up stories such as the world has never seen before.

Yours affectionately,

LJW

Little can be established with certainty of what happened over the next several years. Recently declassified memos reveal that by 1927 the Engine had been removed from Room 40, leaving significant concavities in the dark mahogany floor. Some unverified reports place it on the Channel Island of Sark throughout the German occupation (1940-1945). As Seigneur of Sark during that time, Dame Sibyl Hathaway seems to have succeeded, among other of her many heroic accomplishments, in keeping the Engine hidden away, beneath the slate roof of an inconspicuous granite cottage, for the entirety of the war. If the Nazis had got their hands on this device, it is safe to say we would be living in a very different world today.

Again, the exact circumstances of its passage across la Manche cannot be reconstructed with certainty. But what is certain, indeed what is a fact so incontrovertible as entirely to shape the work we do each day here at The Hinternet, is that by early 1961 the Engine had been installed in the former space of the Conserverie Kervoën & Cie, a sardine- and tuna-canning factory in the Ergué-Armel neighborhood of the Breton city of Quimper. The canning operations had ceased by 1956, and the building was shuttered the following year, only to reopen its doors four years later as the home office of our distinguished publication.

Much else could be written besides, though this will surely have to wait for another occasion, of The Hinternet’s many post-war breakthroughs, and of the delightful camaraderie and spirit of shared endeavor that developed among its employees over the years — of the “quirky” sense of humor, for example, that brought cartoon-like robots and extraterrestrials (really just costumed employees, of course) to its legendary holiday parties. Surely a long chapter of this story will have to be written of the fateful day in 1982 when Wheat’s prediction —some even call it a “prophecy”— proved true, and our very first confirmed message from “the minds at the lower layers” was received.

Admittedly things did not get off to a very promising start, as the particular content of their message hardly signaled any eagerness to cooperate: “Turn back now,” it said (in Akkadian, for some unknown reason: 𒉿𒂊𒊑 𒂊𒈾). We are pleased (at least most of us are) that we declined to heed that warning, and pressed on, and became the source of so many of the stories (upwards of 96% of them, according to our analysts) that the world knows and loves today.

We might also recount the many great setbacks we have faced in our history, as when our Board of Directors, buoyed up by our recent contact with the entities we had begun to call “the Storytellers”, decided to take The Hinternet Corporation public — just before the “Black Monday” stock market crash of October 19, 1987. After that ill-timed foray, the Board, still under the chairpersonship of “la Bretonne”, who had not aged a day since Wheat dispatched her to London more than 50 years prior, somehow managed to eliminate all public records of our brief entry into, and quick exit from, the fluxions and fluences of the free market.

After the crash we scraped by for some years as a humble nonprofit with a shoestring budget — still too skittish to make easy or profitable use of our newfound contact with the Storytellers, and still under a general interdiction placed by la Bretonne, who had begun by 1994 to insist on going by the name “Hélène Le Goff”, on any other “non-mechanical powers we might or might not possess”.

Things began to change again in 1998, when the ExxonMobil Corporation offered us a very small private grant in order, as our contract specified, to “stave off Y2K”. And having delivered on our promise —trust us when we say a massive worldwide computer black-out was only barely averted— we grew more confident in our willingness to access “the deeper layers”, not only for storytelling, but for the sort of real-world “deliverables” that, we had come to see, might justify our existence to those who believe, rightly or wrongly, that we are, as a species, more Homo faber than Homo narrans.

And so, with the dawning of the new millennium, The Hinternet was back.

Of course JSR (the moral person) is not entirely wrong to date to 2020 the beginning of at least a significant part of what makes The Hinternet, well, The Hinternet. For it was in that year, as you surely know by now, that we moved the bulk of our operations to Substack. And it was in that year as well, as we have already hinted, that our fully functional Sempitern Series-7 JSR finally came online — the first Sempitern to be successfully connected in its hardware to the second deepest layer of the Nest.3

The Storyteller module built into our new Series-7 JSR is costly indeed — both in euros, and in energy. We hope to solve at least the latter problem within the next few years through the construction, already begun, of a ring of solar panels placed in Earth’s orbit, entirely encircling the globe. As for expenses, we continue to rely on paid subscriptions… as well, admittedly, when we are left no other choice, as on that old Breton magic taught to Hélène long ago, in a wooded grove, by her great-grandmother, who was 900 years old at the time.

Archives de la Chambre de commerce de Nantes, Série Correspondance commerçante (XXe siècle), Cote CCN/1923/587-D.

It remains an open theoretical question, indeed among the very most important of those addressed in the Hinternet’s research wing, whether it is even in principle possible to connect a Sempitern to the deepest level of the Nest.