I am trying so hard right now not to write. At least not to write in this venue. My aim today is to hit “publish” before I reach 2000 words. We’ll see if I can make it.

My Substack schedule has become simply incompatible with the realization of a couple of long-term projects. The problem is not the time spent actually writing — that I typically do over the course of, say, six to eight hours on the weekend. The problem is the way my anticipation of the writing colonizes my mind for the other part of the week. That’s the thing about intellectual labor: if you’re really doing it, you’re doing it all the time, even if you appear only to be, say, picking up some drain-unclogger at the Franprix. The most productive moment of my day, in fact, generally happens between minute 18 and minute 24 of my daily 24-minute run on the treadmill, at 11.4 km/h, though my fellow exercisers at Les Cercles de la Forme surely have no idea of the hidden work that’s taking place.1

In general I have a great deal of trouble not doing things. It’s almost always easier just to do them. I got a letter from the government the other day. I opened it, and read it; it said they were seeking to suck out what little bit is left of my soul. In particular, it said that the Service Statistique Ministériel en Matière de Sécurité would like for me to go online, enter a special password, and fill out a questionnaire about various matters relating to my safety and well-being. But here’s the thing: the greatest threat to my well-being, and I’m not exaggerating, is having to go online all the time and enter passwords and fill out digital forms. This is the “Singularity” everyone’s talking about, this is Roko’s Basilisk, this is the absolute worst-case scenario. This is already, if you know how to listen, a resounding tattoo that announces, every single day, the total dominance of our robot successors. As I have confessed here on many occasions, they have already crushed me in particular, and like any unfree human I will only do the work I am constrained by force to do; otherwise, you can expect nothing but Bartlebian refusal from me. Censuses, customer-feedback solicitations, grant-application portals, payment-processing platforms, manuscript-processing platforms, all that low-level hum of the motor of our mad mad world, running on the fuel of the data we keep feeding it: I’d rather not.

So I threw the letter away, and then I got an e-mail a short while later reminding me that I hadn’t visited the site yet, and telling me that my participation is “essentielle” and even “indispensable”. I deleted the e-mail too… only to lie awake for hours that same night wondering whether these terms, in bureaucratic French, had been intended as synonyms of “obligatoire”. The survey would have taken 25 minutes, while my preferred course of action deprived me of about two hours of sleep. Was it worth it? Can anyone even imagine coming out on top when faced with such dilemmata?

The same thing happens with e-mails: I get multiple random inquiries every day, and I try to reply to most of them as graciously as I can. The ideal response, I’ve learned, is the one that is warm and supportive, but that, at the same time, positively forecloses on the possibility of any further communication. Sometimes my correspondents fail to pick up on that, and they write again, searching for just a little bit more. So I resolve myself not to reply, and then, too, I lie awake thinking about whether that was the best choice or not. Here the problem is compounded by the fact that these are human beings who are looking for a little piece of me, and not government robots. They could be Christ in disguise, I remind myself. But would Christ-in-disguise be sending me an(other) unsolicited essay in Portuguese about “Leibniz and quantum mechanics”, and asking me for a letter of recommendation, should I deem the essay worthy? I doubt it, but I also hear he works in mysterious ways.

I long for human connection as much as anyone. But I have learned over the years that I should not expect to find it in my inbox, especially when the opening gambit is a quid pro quo. Not even that. Really more just a quid.

My word-count is already getting up there, I know. Sheesh. I just can’t do it. I feel like I just sat down thirty seconds ago. I feel like I am the entire history of Islamic art, operating under a prohibition on representations of living beings, and so I try to concentrate on geometrical patterns and calligraphy, but in no time my letters start getting so ornate again that their terminations now look unmistakably like leaves, and then soon enough like wings, or paws, and then before I know it I’m just leaning into what the more conservative calligraphers could only see as zoomorpholatrous excess, and relishing the infinite forms nature throws my way.

But let’s get down to nitty-gritty, as an ESL-speaker trying to look excited at a California tech conference might say. My plan for the next few months is to keep things minimal here, in the hope of reprogramming my thought-patterns throughout the week, so that they will go instead into my longer-term projects. I worry about losing subscribers, but in reality I suspect a good number of people will respond well to shorter and more to-the-point pieces. Hell, I suspect my subscriber rates would triple or quadruple if I were to start writing 500-word Substack pieces reporting stuff like: “I went to my favorite boulangerie this morning, and I got a croissant that was, I’m not exaggerating, The. Best. Ever. Every bite of it was flaky, heavenly perfection!”

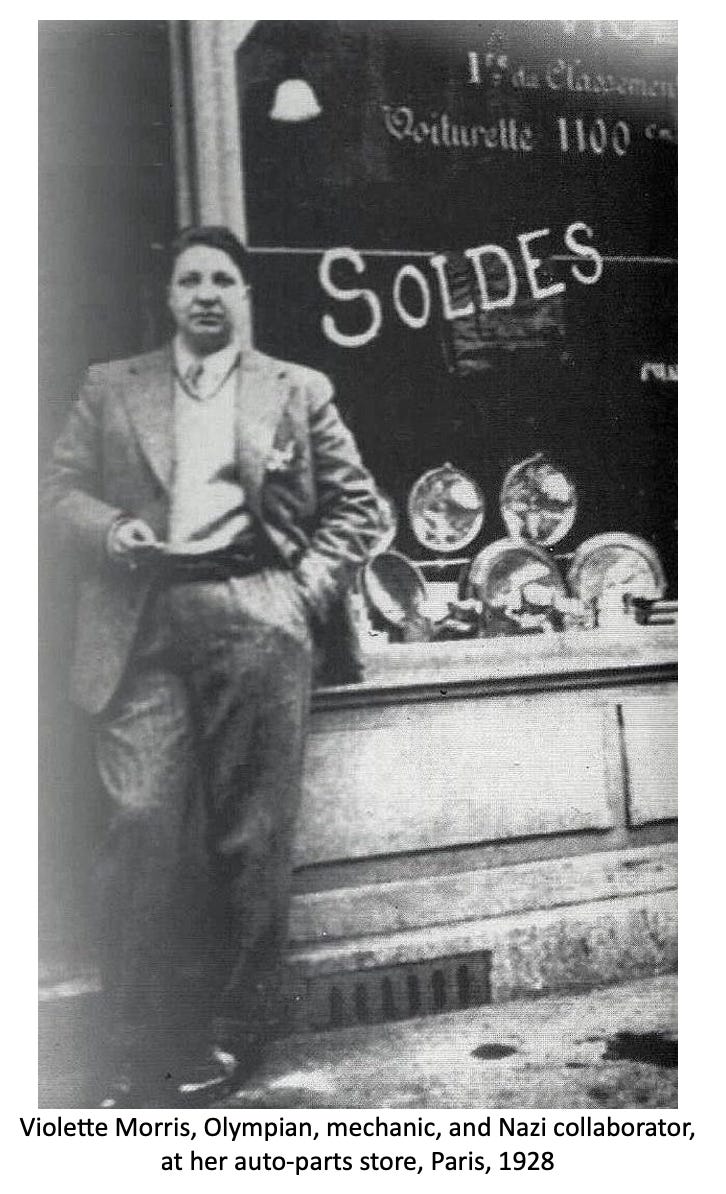

And so on. That’s what most Anglos want to hear from Paris. They don’t want to hear about the incursions of wolves that continued in this city into the 15th century; or about the immortal stage actress Yvonne de Bray’s performance in the 1948 film version of Jean Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, who radiates her own real human personality, at least as traumatized and broken as the mother she plays, and who indeed in real life had lost her partner in 1944, the masculine-presenting Olympic athlete and auto mechanic known as the “hyena of the Gestapo”, Violette Morris, assassinated by a band of maquisards for her collaborationist compromises — which arguably were only slightly worse than Cocteau’s own.2 They don’t want to hear about the traumas of 2015 anymore, which marked the beginning of the “shit just got real” section of my own life’s Paris chapter, a section that has yet to end, and probably never will; nor about the peculiar connotations of the English word chicken in the argot of French commerce, and of the uses and abuses of the English possessive apostrophe, as we see on double display, for example, at this fine local establishment3:

Nobody wants gritty Paris, shitty Paris, violent Paris. This is the only city in the world where, at least among privileged foreigners, there reigns an almost Maoist regime of cliché-enforcement. It’s the only city in the world you’re expected to pretend is uniformly wonderful. And this is a lie that kills, or that at least causes good numbers of young East Asian women to faint every year, upon arriving and seeing all the obvious, shall we say, imperfections, from the misplaced apostrophes to the sprawling migrant bidonvilles, to which Paris’s own lucid writers and thinkers have in fact been trying to draw our attention for centuries.

Okay, that’s all very gritty perhaps, but it’s still not what our imagined German tech-bro would recognize as “nitty-gritty”. So let’s really do it this time.