We’ve never before done what they call, in the scribal industry, a “crosspost” of someone else’s work. But that’s because we never loved anyone enough to do that for them… and that in turn is because no one before was ever Jac Mullen. When JSR heard Jac holding forth recently, over an ice-cold sparkling Saratoga, in a club on the 59th floor above Fifth Avenue, honestly, he thought he was hearing his own speech recited back to him. Only after listening for some time did he realize this was impossible, since the things being said were far too fine, far too perspicacious, for him, JSR, ever to have come up with them himself. Jac shares with The Hinternet an abiding interest in the ongoing transformation in the way we relate to language, especially written language, in the present era. It is therefore only natural that we should seek to absorb some of his work into our “Future of Reading” series. So enjoy it here, but once you have done so please go over to Jac’s own place, After Literacy, to follow his important project and to consider supporting it. —The Hinternet

We seem to be grieving literacy in public lately. Thoughtful essays keep appearing —in The Guardian, The Atlantic, and across this platform— all asking why reading, now, feels so difficult, for ourselves and for our students. A shared anguish runs through these pieces, and rightly so. When literacy is jeopardized, far more than “visual language processing” is at stake; for the written word is bound up with memory, interiority, even a sense of self.

By most accounts, the threat is real. Neuroscientists show how the “reading brain” strains in digital environments; cultural critics trace how ubiquitous computation reshapes attention; educators grapple with pedagogical controversies and students’ dwindling stamina when faced with text. Each week, new evidence—an honor-student who cannot decode basic words, a college cohort that “cheats their way through”—deepens the public alarm.

Are we right to mourn? I think so — at least in part. Sorrow is warranted. But grief alone cannot safeguard what it mourns. To defend literacy, we need to understand what it is, how it took root, and why it now seems so endangered.

This requires a longer view. Literacy is not just a skill, or a right, or a cultural inheritance. It is a complex technology — historically contingent, unevenly distributed, and neurologically fragile. To understand what’s at stake, we have to examine its origins, the struggles that shaped it, and the niche it occupies in the mind.

When we view literacy through that lens, it becomes clear that fluent visual language processing —reading and writing— is a collective, resource-intensive cultural adaptation. It occupies a narrow, hard-won space in our cognitive ecology. Until we see that clearly —and the forces now crowding in on it— we cannot fully name what is at risk, or decide what must be defended.

This ecological perspective, I believe, offers a skeleton key to our current moment. It helps us to see that the societal and cognitive shifts now underway, accelerated by the rise of machine intelligence, echo the dynamics that writing once set into motion: new concentrations of power, new forms of enclosure, and deep transformations in how thought is organized and expressed. Recognizing these patterns does more than clarify the nature of the threat; it opens the possibility of response. It helps us locate paths toward agency that might otherwise remain invisible.

The following four dimensions of this broader ecological story remain largely absent from today’s conversation. Yet they are essential for understanding both the predicament we face and the possibilities still available to us.

1. Writing began as a tool of state control.

Five thousand years ago, in the alluvial plains between the Tigris and Euphrates, early scribes began pressing visual marks into clay — symbols for farming, transactions, gods, debts, sons, slaves. This was not a tool for capturing speech or preserving epics. It was a solution to an administrative problem: how to coordinate labor, track obligations, and render a population visible —and therefore governable— to a central authority.

Cuneiform, the first known script, was an instrument of control. It allowed a small managerial class to fix reality in symbols, to make society legible from above, and to reorganize daily life around the production of surplus. From the beginning, writing was bound to the birth of the state and the consolidation of its power — an asymmetric information technology designed for governance, not yet for the poet.

2. Mass literacy required centuries of redesign and struggle.

The wedge-shaped marks of Uruk did not, on their own, produce introspective readers or democratic citizens. Writing began as a tool of record-keeping and control, and only became a shared infrastructure for cognition after centuries of transformation. That shift required the development of simplified symbol systems, affordable writing surfaces, and new methods of instruction — each of which slowly weakened the scribal monopoly.

Here, scripts like the alphabet did play a crucial role. By reducing the number of symbols and aligning them consistently with speech, such systems made writing newly learnable — and, in principle, accessible to a much broader population. To realize this potential in practice, and achieve something like mass literacy, required further advances in material and institutional support: the invention of printing, the spread of public education, and coordinated campaigns for basic literacy. Ironically, this global diffusion is reaching its widest extent just as the role of text itself begins to recede.1

This slow transformation underscores a crucial lesson: turning a tool of power into a widespread cognitive commons is a long, arduous process, contingent on new forms that serve to democratize access and use.

3. The reading brain is an “unnatural”, fragile achievement.

While contemporary discussions often focus on what we read or how we teach reading, the deeper truth is that literacy itself is an astonishingly fragile achievement. We are not born readers. As neuroscientists like Maryanne Wolf and Stanislas Dehaene have shown, building the reading brain requires overwriting some of our innate visual processing habits —such as mirror invariance— and forging new, resource-intensive neural circuits.

Widespread literacy, then, is not a natural baseline but a costly ecological accomplishment. It depends on sustained, large-scale societal investment in both cultivation and maintenance. If that investment falters —or if new modes of communication arise that are less cognitively demanding and more closely aligned with our oral-auditory predispositions— then this hard-won literate ecology can erode rapidly.

In other words, mass literacy is not simply a skill that might fade. It is a complex cognitive adaptation —difficult to build, easy to displace— and, if outcompeted, literacy may once again become the province of a specialized elite.

4. Like writing in Sumer, AI is making people legible to a new system of power.

What happened in Sumer —the co-emergence of a new record-keeping technology and a new form of social organization— is, in a sense, happening again, but on a planetary scale. A powerful new information system —AI, along with its data-harvesting ecosystems— now tracks, tags, and parses human behavior with unprecedented reach. As with writing in the early state, the system is largely opaque to those it governs: it reads us, but we do not easily read it.

Like cuneiform at Uruk, AI is enabling a new mode of social organization, directed by a new kind of elite. Its economic form has been named —“surveillance capitalism”— but its political structure remains undefined. What is clear is its purpose: the production of a new, extractable surplus.

Where Sumerian tablets helped generate predictable grain yields, today’s machine intelligence structures the world to produce predictable data, attention, and behavior. Through continuous modeling and subtle feedback, human action is rendered legible and brought under algorithmic management. This marks a second enclosure — not of land, but of the cognitive commons itself.

Naming the Problem

1. We are selecting for affordances, but should be selecting for effects.

Historically, we accepted literacy’s steep training cost because it offered a unique bundle of symbolic affordances: durable storage, precise retrieval, spatialization, and combinability. These were not luxuries — they were prerequisites for disciplines like law, science, literature, and philosophy.

Now, AI-mediated oral–auditory systems provide many of those same affordances —cloud memory, instant query, spatialized workspaces, speech-to-anything translation— at a fraction of the acquisition cost. We do not need ten years of schooling to learn to ask a language model, by voice, to store or retrieve language.2

If new media outperform text on primary utility, ordinary selection pressure may displace literacy from its cultural and cognitive niche. But while these systems may replicate many of the affordances of textuality, their effects may be fundamentally different. And when it comes to literacy, it is precisely the secondary and tertiary effects that carry disproportionate value.

These effects include recursive empathy, long-horizon abstraction, disciplined counterfactual reasoning, interiority, and the capacity to entertain multiple perspectives over time. They emerge slowly, through sustained symbolic engagement. They are difficult to measure, easy to overlook, and prone to erosion when unattended.

To be clear about the mechanism: our society selects for the affordances of a medium —speed, ease, efficiency— not for its effects. And it is the effects of literacy that hold its civilizational value. This is the critical point: those deep cognitive and ethical capacities are not being selected for. They are not easily monetized or optimized. They rarely register on the dashboards that guide decision-making.

This raises some strategic questions:

Which of literacy’s secondary effects are essential for a flourishing society?

Which of those might be recreated —at least in part— through non-textual or hybrid means?

Which by contrast are inseparable from deep textual engagement, requiring deliberate cultural protection and continued use of the written word itself?

2. AI is externalizing attention, just as writing externalized memory.

Writing externalized memory. While this eventually gave rise to the shared cognitive commons of literacy, its initial effect was consolidation — the enclosure of resources, the legibility of populations, and the emergence of centralized control. Only over centuries —through the invention of more accessible scripts and wider systems of instruction— did that tool become broadly available.

Today, machine intelligence is externalizing attention. It models it, redirects it, and applies it at scale. And once again, the earliest effects are consolidating rather than distributive.3

The risk of this second externalization —if left unshaped— is the emergence of a deeper enclosure: not of land or labor, but of perception, memory, and desire themselves. The ways we notice, recall, and orient our will may be increasingly governed by systems we do not see and cannot easily interrogate.

In the hands of the few, large-scale behavioral modeling could begin to function as a form of ambient governance: a one-way mirror that interprets our impulses while offering little in return. To redirect that trajectory, we will need to open its symbolic architectures, rethink its governance structures, and embed it in civic frameworks capable of supporting reciprocity and shared agency. And we will need to do so far more quickly than the time it took for scribal memory to become collective literacy.

The Task Ahead

At After Literacy I will be going more deeply into these dynamics — how literacy might be outcompeted, what specific cultural benefits we risk losing, and how we might defend or reimagine them in an AI-driven world.

We have, as a species, been here before. We managed to transform writing, initially an instrument of state coercion, into literacy — a powerful infrastructure for widespread human thought, creativity, and self-understanding. A means of accounting became a means of combinatorial creativity. Having done it once, we can perhaps do it again with AI.

But this time, we do not have centuries. It took a thousand years from the invention of writing at Uruk to its first recognizably literary uses. It took another thousand for portable, alphabetic systems to make mass literacy possible. Today, we may have five years —perhaps less— to guide AI from a centralized instrument of emergent power into a decentralized, self-contained, shared cognitive substrate capable of strengthening human autonomy rather than displacing it.4

How? I don’t claim to have all the answers. But I have ideas about where some of them may be found. And I invite you to join me in the search.

A first essay —on what it means to externalize attention— will appear soon. I hope you’ll read along, question, challenge, and contribute. This moment is fragile, critical, and still malleable, if we act with insight and care.

Whether we fortify the niche that literacy still occupies or apply its lessons to guide the design of new symbolic systems, the task is the same: to hold open the possibility of a cognitive commons, and to preserve —while we still can— what makes agency, reflection, and mutual recognition possible.

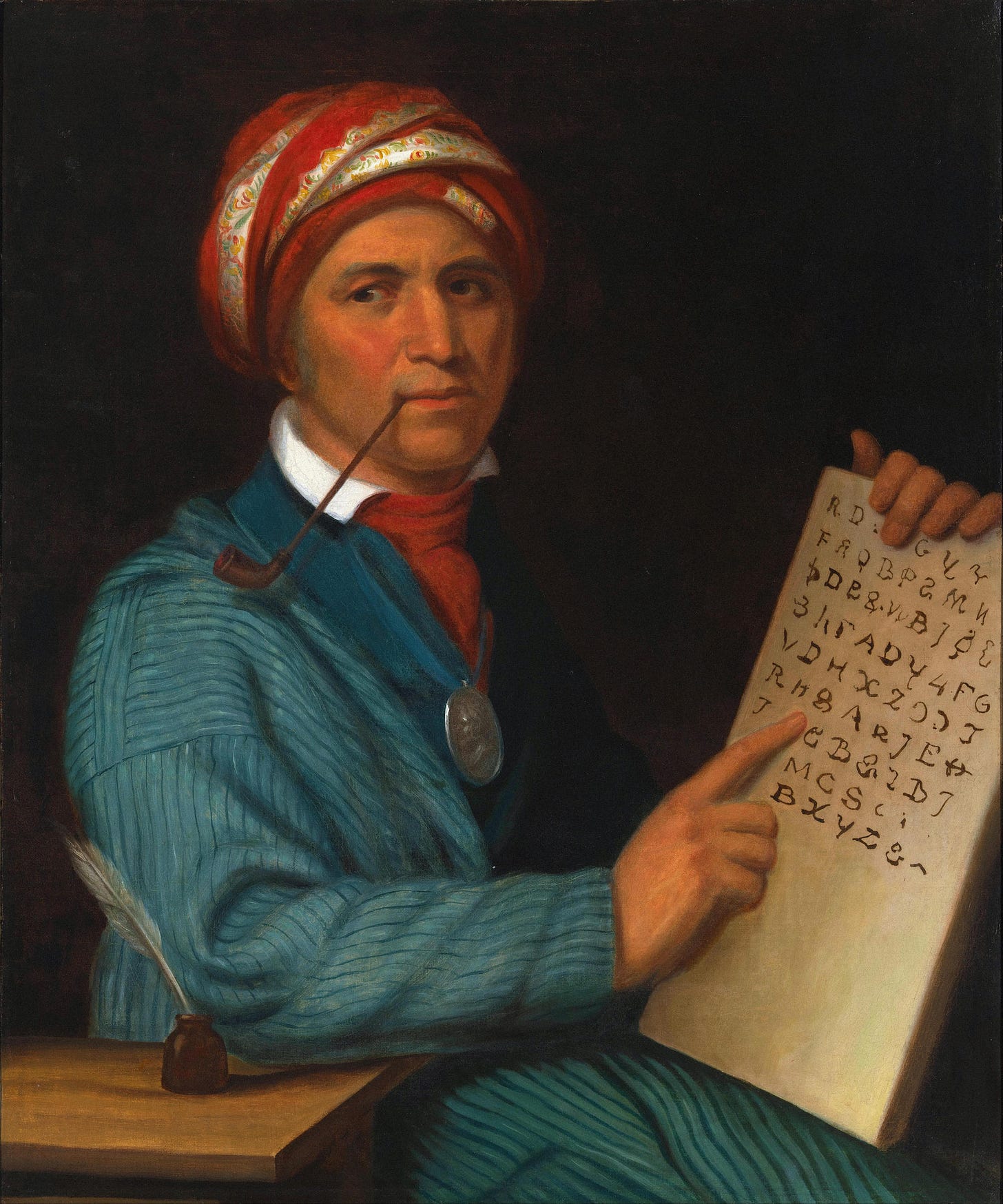

If my emphasis on the alphabet seems pointed, it’s because I see its structure —not its cultural lineage— as crucial to understanding how writing becomes broadly accessible. I’m working on a longer piece exploring claims of “alphabetic exceptionalism” and the debates they’ve sparked, but for now I simply want to foreground a set of functional properties that matter when it comes to decentralizing technologized power. The kinds of writing systems most effective at widening access tend to share a few features: First, they contain a finite set of core elements (ideally under fifty); second, those elements correspond consistently to the same level of linguistic structure (such as phonemes or syllables); third, they can be combined to generate an indefinite range of utterances. The alphabet’s early development did not immediately democratize literacy — evidence suggests that scribes were often its first adopters and gatekeepers. But when the goal is to expand literacy beyond a small class of specialists, writing systems with these characteristics are almost always chosen. This is true across cultures and eras, from the spread of Cyrillic and Hangul to the development of the Cherokee syllabary by Sequoyah (a figure After Literacy will return to frequently). While not an alphabet in the strict sense, Sequoyah’s system meets the same core criteria for a script that lowers the barrier to entry and supports distributed use.

Similarly, Neil Postman once observed that while many struggle with reading comprehension, “no one struggles with television comprehension”.

I don’t intend the observation —that just as writing externalized human memory, machine intelligence now externalizes human attention— merely as a metaphor or even as an instructive analogy. I mean it more strictly: that a structural and functional isomorphism exists between these two externalization events. While I doubt I’m the first to notice this parallel, I’ve found it remarkably generative as an organizing principle. Consider how attention functions: what we attend to gains resolution within our internal model of reality; what we neglect fades. Attention determines what enters consciousness and what receives cognitive resources. It is no coincidence that we are seeing both the rise of an “attention economy” and an increasingly malleable symbolic reality — reaching a terminal expression in the proliferation of deepfakes and synthetic media. This shift is occurring precisely as attention itself is set loose to roam the storehouses of our externalized memory systems. The result is a cascade of feedback loops and emergent properties that we are only beginning to understand.

This is less a "calculation" and more a "hope." It is likewise more a "doomsday clock" than a timeline, insofar as certain developments could bring us further away from midnight, and perhaps absolute midnight will never exactly be reached. I will share more about this later. Any estimate ought to consider: the rate of AI progress; the rate at which capital concentrates in the hands of a global micro-elite; the rate of automation; and a variety of other indicators, including the feasibility of volitional autonomy within a given environment.

This is a great article.

One minor complication about the statement that writing first developed from its administrative power:

I think the current interpretation of the emergence of Chinese characters is that they were used in religious practices, most importantly the reception of messages from spirits, before the development of a literate administration. So, by the time the state developed enough to use characters, it had to respect them as sacred objects. I wonder sometimes if this sacredness explains why they put up with a very unnecessarily complicated writing system.

There’s a little bit of an analogy with the way that some people today treat literacy as necessary to communicate with the culture, or with the great thinkers, or however they may put it.

I admit to being dragged kicking and screaming and in deep denial into the post-literate age. This helped me -- a highly literate person of a certain relatively advanced age -- to calmly consider what is happening, though it still fills me with despair at what will be lost.