The New Yorker on the “Crisis of Attention”

And a Long Interview on Sakha, on Oral Epic, on Why Philosophers Should Study Indigenous Languages, &c.

Regular readers of The Hinternet will have heard this song and dance before, but this time I mean it: I am, at least this week, on “book leave”, and I am not in any position to write, alongside my original, carefully researched and constructed book manuscript, an original, carefully researched and constructed 5000-word essay here as well. Instead I will direct you to some other venues with some engaging reading that has at least something to do with my work.

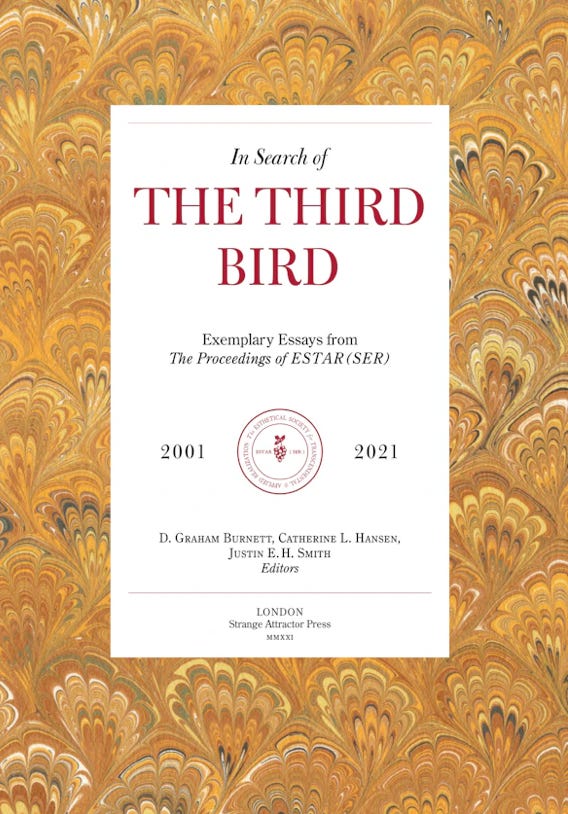

There is a long feature piece in this week’s New Yorker by the excellent Nathan Heller, entitled “The Battle for Attention”, which details the various activities of the Order of the Third Bird, and explains how these amount to a form of resistance to our new economic and political order of ubiquitous and incessant attention-fracking. Here’s the longish passage that focuses on the aspect of Birdishness that interests me most, namely, the research undertaken by members of the ESTAR(SER) collective, including myself, some of which was recently published in the 2021 opus, In Search of the Third Bird:

Unable to refrain entirely from academic habits, a subgroup of Birds have produced their own outlandish body of work. Early in the last decade, Burnett and a couple of his colleagues began writing and assigning articles for an imaginary peer-reviewed journal devoted to scholarly study of the Birds. At first, the project was a way of sharing ideas about the Order’s attention work without writing about it directly. (Like the Birds themselves, I was allowed to participate in actions on the condition that I not describe the experience in print. “My fear,” one longtime Bird said archly, “is that people will mistake the description of the thing for the thing.”) But many enjoyed writing for the imaginary journal of the so-called Esthetical Society for Transcendental and Applied Realization (now incorporating the Society of Esthetic Realizers)—or estar(ser)—and some seem to have enjoyed it more than their real work. When Burnett and two co-editors culled a selection, in 2021, they ended up with a book more than seven hundred and fifty pages long.

Landing somewhere between “Pale Fire” and the formal irony of Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, the volume, called “In Search of the Third Bird,” is rendered in the voice of hapless researchers trying to chase down the elusive Order. The articles are not pure fiction—they include real attention scholarship—but neither are they a hundred per cent objectively true. Counterfactual histories filter in, cross-referencing one another. Some articles are by real scholars, while others run under birdy pseudonyms (“Molly Gottstauk”) with preposterous author biographies. Justin Smith-Ruiu, a writer and a professor at the Université Paris Cité as well as an editor of “In Search of the Third Bird,” touted to me “the world-making dimension” of it. “Our idea was: Let’s turn academic practice into an art form,” Smith-Ruiu said.

Even many members of the Order describe the estar(ser)work as a bit precious. “The amount of effort in the book is huge, but its effect is, uh, marginal,” Adam Jasper said. “It sort of fits into the Birds’ ethos of not being concerned with inputs and outputs.” In a sense, it is bizarre that estar(ser)—an acronym that, being two forms of the Spanish “to be,” is largely un-Googleable—has become the Order’s public front, mounting lectures and exhibitions across the country. (Last year, it had an exhibition at the Frye Art Museum, in Seattle; this spring, it will present a show at the Opening Gallery, in Tribeca.) But that improbability is the point. Catherine L. Hansen, an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo and another editor of the book, describes the project as a defiantly playful performance of humanities scholarship’s twenty-first-century limits—the way that disciplines are increasingly pressed to approach the work of human imagination with the objective rigor of a science.

Naturally I would have liked to see more on the book than these few paragraphs, as it absorbed so much of our creative energy for so many years. But it’s no criticism of this particular article that it does not provide more. I can think of no one who might have done a better job than Nathan of distilling and conveying the essence of this nebulous movement, whose members are often frustratingly fugitive and self-sequestering. It’s really just such an honor and a gratification to read his piece!

Oh, I guess I do have one small complaint: I hate, but really hate, McSweeney’s. Every time I start reading it I think: Am I reading “Reader’s Digest Presents: The ‘Lighter Side’… Of Graduate School!”? I certainly never thought of McSweeney’s as one of our models or inspirations (in fact Reader’s Digest itself would come far higher on the list). But on the other hand Nathan compared the work to Pale Fire, so really, how dare I complain!

The other piece I wanted to share is an interview I did with Jonathan Egid, who is one of the most interesting young scholars of the history of philosophy working today. He wrote his Ph.D. on the (possibly non-existent) 17th-century Ethiopian philosopher Zera Yacub, and learned Ge’ez in order to do so (without that language, pretty much anything anyone says about the existence or non-existence of the philosopher in question is worthless). In the course of his work Jonathan became interested, as I am also interested, in the troubling relationship between philosophy and what I would call the “languages of empire”. That is, it almost seems as if what gets to be called “philosophy” at all is a function not of the content or method of the work in question, so much as its belonging to the linguistic communities of the world’s centers of power. This, I’ll note in passing, is a form of exclusion so comprehensive and total that the vast majority of anglophone philosophers who talk about how much they value “inclusion” don’t even notice it.

Anyhow, Jonathan began thinking really hard and really seriously about what philosophy looks like when it occurs far beyond the metropolises, in marginal languages, often through oral transmission, and accordingly began exploring this question through a new interview series called “Philosophising In…” He has invited a number of scholars to speak with him on this issue from various angles, notably Bachir Diagne, who, as a consummate cosmopolitan working in English and French, retains a deep interest in what it might mean to do philosophy in Wolof.

And more recently Jonathan talked to me about how I conceive the value of my own now-years-long study of Sakha for my work as a philosopher. Here is an excerpt (please excuse my conversational tics; this, too, is oral transmission):

One important thing that isn’t distinctly Sakha, or even distinctly Siberian —I think we will certainly find comparable representations in traditional cultures of the Americas in particular— but is still something important that I think any philosopher should take an interest in or should spend some time trying to understand, are those groups of people that have a broadly animistic conception of nature. Why should we spend time doing this? Well, because I would say it’s the default relationship to nature in most times and places in human history and prehistory. It’s the way human beings have generally related to the world around them. Humans view a world that is teeming with spirits or animate forces that have wills of their own that need to be placated, and most human energy goes into managing the relationship with these forces. These forces include wild animals, bears and so on, but also of course natural phenomena like lightning. I would go so far as to say that this relationship to the world is our ‘factory setting’, so to speak —that’s the way our brains were configured—, and to appreciate it, to work your way into it, really helps to get a clearer understanding of how the human mind works. Some cognitive scientists like to talk about the idea of the brain as a ‘hyperactive intentionality detection device’ — think of the question ‘why do we feel like we're being watched if we walk down a forest path in the middle of the night?’. I can think of two ways to respond: you could say ‘oh that's just superstition, get over your superstition you fools!’; but we might also see it as telling us something about how our minds work. So that’s one general point I feel might be useful for philosophers: I feel like I have a much better understanding of what it is to to really respect bears and lightning and other parts of reality in a way that I did not before.

Read the rest of the interview here.

And please consider subscribing, if you have not done so already, to encourage me to come back to this venue with more original writing once I’m done with my “book leave”.

—JSR

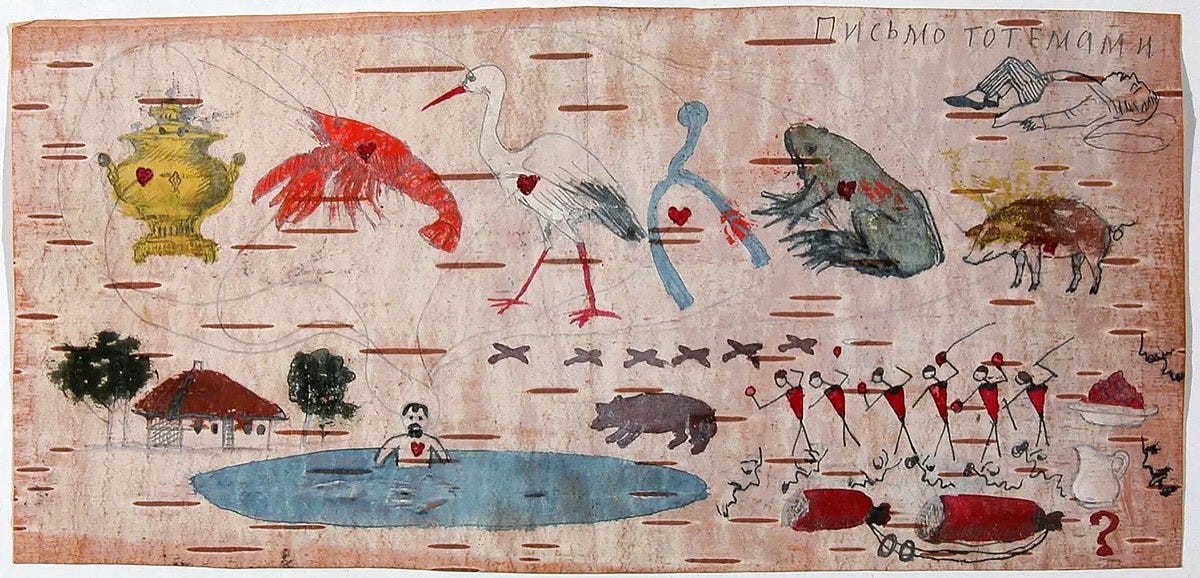

Image: Volodya Ulyanov,1 “Письмо тотемами” [“Letter with Totems”], 1882.

Also, if you haven’t done so yet, please do order a copy of In Search of the Third Bird for yourself!

Yes, that Volodya Ulyanov.

This was hilarious — thank you so much. I’m dying here. No, I mean that litera

I checked Jonathan Egid's writings on the issue of Zera Yacob, and he seems to lean to the side defending that he was the real deal, and his book not a forgery. I recommend Isaac Samuel's recent post for those interested in the debate https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-radical-philosophy-of-the-hatata