“The starry heavens above me and the moral law within[, and the sediments of the Memel, and the amber deposits at Palmnicken, and the moss on the rocks beneath the snow that the reindeer pierce with their tongues to lick off, so I’ve read, in Lapland].” —Immanuel Kant [more or less]

1.

A while back I resolved that any mention of the Sakha people in a front-page New York Times article was going to get a write-up here at The Hinternet. My day has come. In a March 12 piece in the Times, entitled “Ukraine-Backed Russian Exile Groups Stage Assaults on Moscow’s Turf,” we learn of the “Siberian Battalion”,1 a scrappy ensemble of fighters composed of the members of various Turkic and Mongolic ethnic groups from within the Russian Federation, now fighting against the country of their nominal citizenship. The article reports that the unit was “formed last year in Ukraine”, drawing from “ethnic minority groups in Siberia, such as the Yakuts [Sakha] and Buryats.” We hear from “one soldier from Yakutia, who used the nickname Vargan.” Vargan tells us: “I don’t consider myself Russian. I am not a traitor.” His group has been responsible for several drone attacks, and even night-time raids well into Russian territory.

A week or so earlier I had already watched footage of Vargan in a YouTube video entitled “Якут, бурят и татарин — россияне воюют против России” [“A Yakut, a Buryat, and a Tatar — Russian Citizens Fight against Russia”]. The video was released by Настоящее Время [The Current Time], an online media operation owned and managed by what used to be called Radio Free Europe. It’s a bracing watch. Vargan and the Buryat soldier speak to the interviewer with their faces showing, while the Tatar, who identifies himself as a nationalist poet, conceals his identity with a mask. Vargan says that back in the Sakha Republic he had made good money as an ichthyologist, studying fluvial ecosystems. He speaks of his concern about the pollution of Yakutia’s rivers, and complains of the “chaos that Moscow has unleashed throughout the world.” He says that the first reason he is fighting is for his mother back in Yakutia, who had suffered a serious illness and landed in intensive care, where, as a result of what Vargan describes as the doctors’ negligence, “she was transformed into something non-human, just lying there like a living corpse.” You can see how much he loves his mother, and how deeply this incident, much more than the war itself, has turned his world upside down.

“Vargan” is the Russian word for what was once commonly known in English as a “Jew’s harp”, but more recently has lost some of that arbitrary ethnic specificity under the newer and far less flavorful designation of “mouth harp”. The Russian word is of disputed etymology, and may come either from the Greek ὄργανον (think here of Marin Mersenne’s reflections on the “organic” quality of musical instruments), or, which appears more likely, from the Old Slavic варга/varga, meaning “mouth”. In its original form, as a simple reed, the mouth harp is one of the oldest known musical instruments in the world, perhaps as old as drumming, which is as much as to say as old as humanity itself. Even orangutans have been observed in the wild blowing on reeds and manipulating them continuously to alter the pitch, a practice primatologists have described as evidence both for “proto-language” and “proto-music”, which may of course turn out to be the same thing.

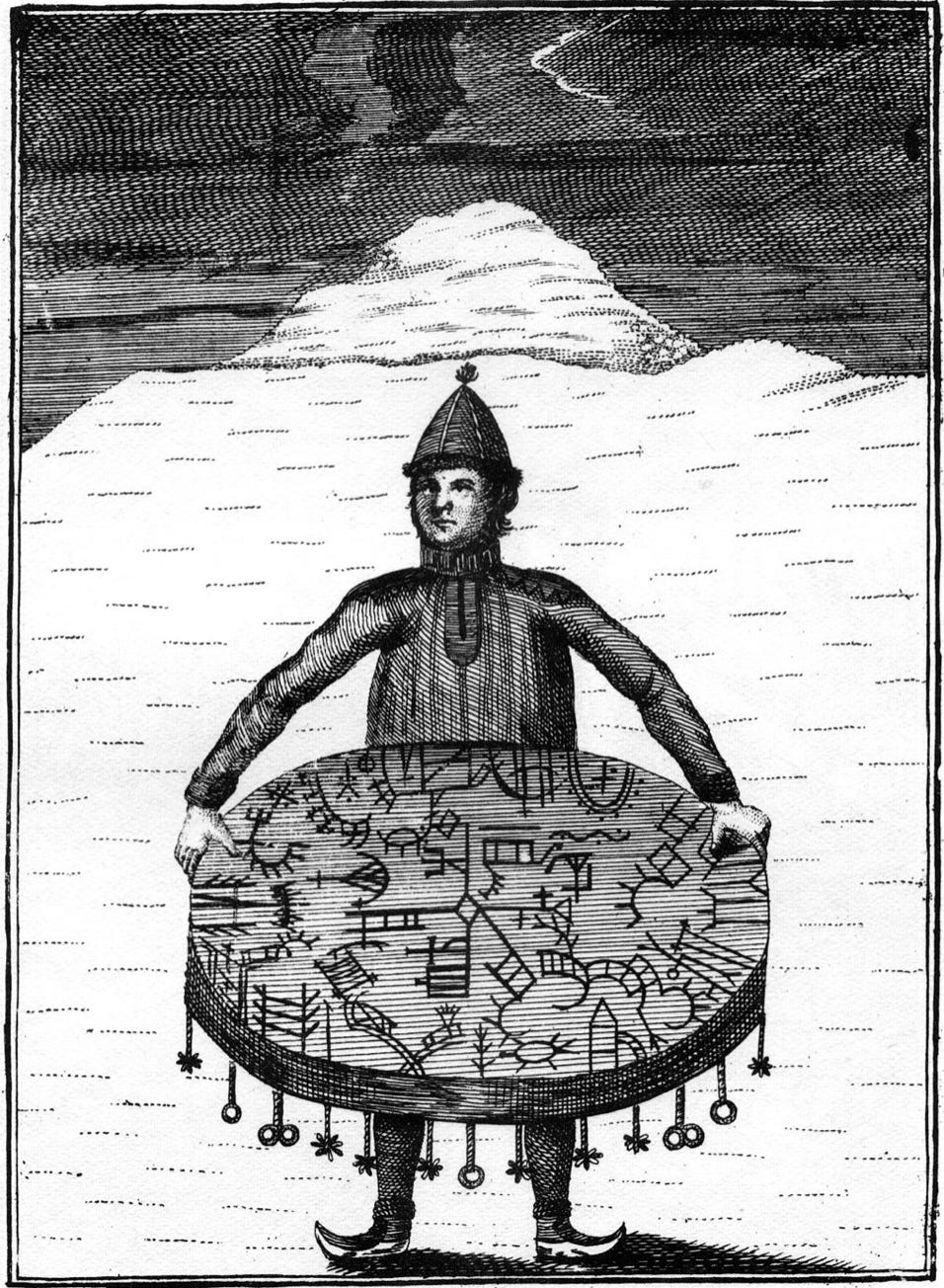

The mouth-harp is also a key element of traditional Sakha culture, both in the context of shamanistic ritual, and also as an instrument used simply to enhance the pleasure of communing with nature. Its Sakha name, хомус/khomus, is the same as the word for “reed”. The original reed instrument is literally just a blade of grass, even though the Sakha have been making their own хомустар out of metal since at least the period of their ethnogenesis. When they emerged as a distinct ethnicity around the 13th century, the Sakha already shared the gift —and the curse— of metallurgy with the Mongols.

The Russian Far East endured significant turmoil in the years following the Russian Revolution. Some good number of ethnic Yakuts joined the side of the White Russian resistance — in vain, as the Yakut Autonomous [sic] Soviet Socialist Republic was anyway founded by 1922. But their resistance was mostly against the Bolsheviks, not the Russians in general. In this respect Vargan the volunteer soldier in Ukraine is among the very first of his people to take up arms against the Russian Empire since the defeat of the great Yakut warlord Tygyn Darkhan, who died in a Russian gaol in 1632, bringing about the eventual end of the Yakut Rebellions, and another 400 or so years of forced tribute paid to Muscovy by these honorable Northeast Asian people. In exchange for what, exactly? Protection? From whom? The Mongolians? The Chinese? Would a return to those imperial spheres of influence be any more limiting of their freedom and self-determination?

2.

The Times article was only the first of two unexpected mentions of the Sakha in my readings this week (there were, as every week, several expected ones). The second mention is one that I in fact already knew well, and should have expected, as I return to it once a year, which is to say every time I teach §63 of Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment (1790). There we read:

The Laplander finds in his country animals by whose aid [human] intercourse is brought about, i.e., reindeer, who find sufficient sustenance in a dry moss which they have to scratch out for themselves from under the snow, and who are easily tamed and readily permit themselves to be deprived of that freedom in which they could have remained if they chose. For other people in the same frozen regions marine animals afford rich stores; in addition to the food and clothing which are thus supplied, and the wood which is floated in by the sea to their dwellings, these marine animals provide material for fuel by which their huts are warmed. Here is a wonderful concurrence of many references of nature to one purpose; and all this applies to the cases of the Greenlanders, the Laplanders, the Samoyeds, the Yakuts, etc.

Whenever I teach the Third Critique I do so in my capacity as a philosopher, not as a Yakutologist, and so I did not mention in class, but will mention here, that this is by no means the only such sweeping survey of circumpolar cultures in Kant’s writing. The Greenlandic Inuit, the Sámi, the Nenets, and the Sakha (to update the relevant exonyms, though in a no less arbitrary way): all these cultures fire the philosopher’s imagination no less than the starry heavens, and certainly with more precise geographical and proto-ethnographical information than what he showcases in his comparable, if much less frequent, invocations of the “South Sea Islanders” or the “New Hollanders”. For his knowledge of Lapland Kant is perhaps relying on Johannes Schefferus’s Lapponia (1673), or on Carl von Linnaeus’s Flora Lapponica (1737). Whether Kant had access to this latter text or not, we know that the French naturalist Buffon drew significantly on Linnaeus’s voyages in his own Histoire naturelle, which is a constant touchstone throughout Kant’s work. For the Nenets and the Sakha Kant could be drawing on Nicolaes Witsen’s Noord- en Oost Tartarie (1692).

While he often ranges far from home in his examples, in the Third Critique Kant’s reflections on ecosystemic balance —or, if you prefer, on the interconnection between relative and absolute ends in nature— are just as likely to be drawn from his observations of the Königsberg region, which, famously, he never left (at least not corporeally). Thus, from earlier in the paragraph already cited:

Now the deep sea, before it withdrew from the land, left behind large tracts of sand in our northern regions, so that on this soil, so unfavourable for all cultivation, widely extended pine forests were enabled to grow, for the unreasoning destruction of which we frequently blame our ancestors. We may ask if this original deposit of tracts of sand was a purpose of nature for the benefit of the possible pine forests? So much is clear, that if we regard this as a purpose of nature, we must also regard the sand as a relative purpose, in reference to which the ocean strand and its withdrawal were means.

Note that here Kant understands his own hometown, like the homelands of the Sámi and others, as distinctly “northern”, which is to say as a place whose natural and human destinies are shaped by the geographical extremities that characterize the globe’s less temperate regions, the regions less naturally amenable to human life. A case might be made in this respect that Kant is not so much a German philosopher as he is, more specifically, a septentrional one.

Of course, the great difference between Kant’s Königsberg and, say, the ostrog of Yakutsk, founded by the Russians in 1639, is that the Livonian march-lands had already begun to be subordinated to the transformative will of Enlightened civilization and its ancestors beginning with the Teutonic Crusades of the 12th century. These annihilated the Yotvingians and several other indigenous Baltic and Finnic groups, the various marsh-dwelling чудь/chud’ whom Peter the Great would still be looking to eradicate in order to clear the way for the founding of St. Petersburg in 1703. By the time Kant is writing the region has been thoroughly Christianized and, at least among the landholders and city-dwellers, thoroughly Germanized, even if the common people remained mere чудь, often perceived by the Junker gentry as not even warranting a distinct ethnonym. This was still a region far more suitable for margraves than for princes, a liminal zone between two great empires. But there was no longer any question of “why the Balts should exist at all”, since they had long been enfolded into the sphere of civilization that alone, Kant thought, made life worth living.

Not so for the Yakuts and the Laplanders. Following his brief description of boreal ecosystems above, Kant proposes provisionally that the only possible “for which” of all this moss and whale blubber and reindeer milk and so on is the life of the human beings who benefit from the whole arrangement at the highest trophic level. But on reflection, this seems implausible to him:

[T]o say that vapor falls out of the atmosphere in the form of snow, that the sea has its currents which float down wood that has grown in warmer lands, and that there are in it great sea monsters filled with oil, because the idea of advantage for certain poor creatures [i.e., the Sámi] is fundamental for the cause which collects all these natural products, would be a very venturesome and arbitrary judgment.

If the only absolute end towards which all these lesser subordinate ends are tending is the sustenance of Arctic hunter-gatherers, Kant reasons, it is difficult to see why any of it should exist in the first place. The only sense-giving path forward, in that light, is to colonize the Arctic, to absorb it into the empire of reason, just as the Teutonic Knights did long ago for the Balts, and just as the Russians are now doing for —or to— the Yakuts. The Russians were probably not the most reliable deliverers of this new sort of Good News, of course, though unlike in Marx we don’t detect in Kant any obvious low estimation of the readiness of the Russians to bring Light to the world. He was a Königsberger, a port-dweller, a stationary cosmopolitan. He never travelled, but he did see all sorts of people come and go, among them a number of Russians who seem to have made, overall, a good impression.

3.

When I was in Kaliningrad in 1999 I visited Kant’s grave, as one does when one is young (I would never visit a philosopher’s grave today — what do I care where their mortal remains have rotted?!). I was surprised to see there significant and unmistakable evidence of a recent visit from a group of local neo-Nazis. Vodka bottles, cigarette packs, and sundry white-power symbols had been left next to the monument, with its bilingual inscription of the iconic “starry heavens above me” line — not as vandalism, mind you, but as tribute and honor, so hungry were these confused Russian youths for any enduring testimony to their city’s German past. In a pinch, Kant can stand for Nazism too.