The World Is Everything That Is the Fall

Necessity and Contingency from Aesop to Wittgenstein

Here at The Hinternet we seldom so much as acknowledge the seasonal calendar — while all you trend-chasers are sharing tips about this year’s best summer beach reads, or making lists of the worst Christmas songs ever, we continue to operate, most of the time, as if outside of time altogether. There are however some early subtle signs in the air of an annual metamorphosis for which we cannot but acknowledge our love. Fall. What a season, and what a word! We have long admired listopad, the Polish term for November, which translates literally as “leaf-fall” (Ukrainian and White-Russian follow the same pattern). But somehow it never occurred to us that the English “fall” as well describes what the leaves will soon do (“spring”, too, honors the leaves at the beginning of this cycle), having been introduced as a blunt alternative to the French-derived “autumn”, etymology unknown, in the 16th century.

And falling, as Erin Endrei shows in her first contribution to The Hinternet, is a variety of motion in space heavy with philosophical significance. Spinoza says somewhere that if a falling stone could contemplate its own plight, it would tell itself it was falling of its own free choice. Do the leaves have a similar thought, we wonder? Or do they recognize the necessity of their circumstances? And if their fall is in fact necessary, why does the word we use to describe it have such a complex historical and conceptual connection to contingency? In her elegant and surprising juxtaposition of Aesop’s fables and of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, Erin helps us to go some way towards answering these impossible questions. —The Editors

0.

There are no primary sources for Aesop’s fables, if the emphasis here on the proper name is taken to imply that the name’s supposed referent wrote them down. If he existed, he almost certainly did not do so. Socrates knew the fables attributed to Aesop well enough to versify them in his last days, according to Plato in the Phaedo, but written compilations are not known to have been produced until the following century.1 Of modern editions, it is Ben Edwin Perry’s Aesopica: A Series of Texts Relating to Aesop or Ascribed to Him Or Closely Connected With the Literary Tradition That Bears His Name, Collected and Critically Edited, In Part Translated From Oriental Languages, with a Commentary and Historical Essay (1952) that contains the sources closest to “primary” in this context, being a compilation of the earliest written versions of the fables in Greek and Latin.

Perry was not the first to exercise caution with respect to the fables associated with the subject of the popular ancient biography Vita Aesopi.2 His earlier monograph had devoted considerable scholarly attention to the Vita, presenting one of the earliest codices of it, the Vita G, in edited form.3 According to Lloyd W. Daly in Aesop Without Morals (1961), a work itself heavily indebted to Perry’s scholarship, it was not always assumed in the ancient world that all fables of the kind today called “Aesop’s” originated with the same person.4 They were termed Aesopic, as Perry also approves of calling them in the General Preface to Aesopica and in his earlier work on the subject.5 Both he and Daly avoid applying to them the possessive form of Aesop’s name. To do so without qualification, their scholarship suggests, is to run roughshod over the history of the fables’ formulation, variation, and supplementation down the centuries as tradition.

However we refer to the short tales by which that tradition is composed, most of us today have probably thought about them only rarely since our earliest school days, perhaps turning our attention to such apparently childish stories (or, as Daly puts it, “moralistic pap”) only on the odd occasion when we have witnessed, if not levelled or suffered, accusations involving the phrase “sour grapes”. The most special and important kindergartener of my acquaintance, for her part, has no favourites, as she does not yet abide any of them at all. On the last occasion of my trying to read “The Tortoise and the Hare” to her—quite a while ago indeed now—she was appalled by the ending, despite my attempts to explain its heartening moral. This was because she “wanted the hare to win”, a desire she justified in turn with the claim, entirely true in a sense, that it was he who “was supposed to win”. Neither did the next fable we tackled, “The Vain Jackdaw”, successfully “land”. For once one puts beautiful feathers upon oneself, then how can one fail to be beautiful? And the bird had put beautiful feathers upon herself. In what some may call didactic defeat, others gentle parenting, the volume has since remained in its place on the shelf.

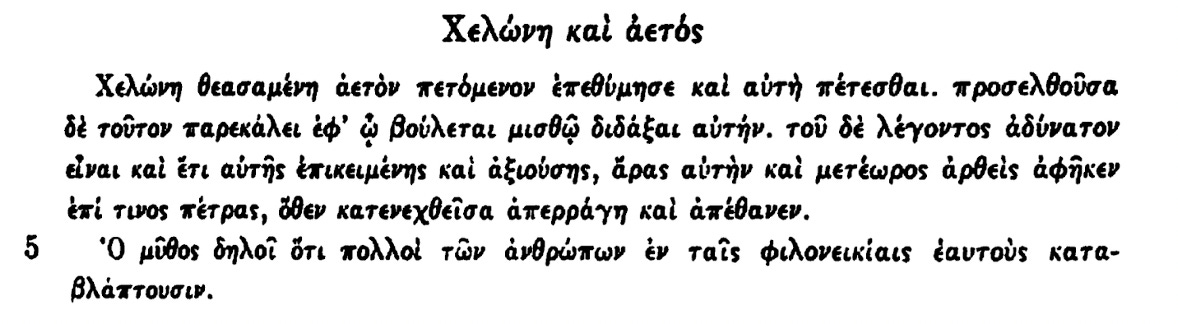

One fable from Aesopic tradition that is less a favourite of mine than something that has burned itself in my memory, like Larkin’s jauntily tetrametric advice about having kids, is indexed 230 in Aesopica: “The Tortoise and the Eagle.” It may be read in several languages on the academic Laura Gibbs’ impressively detailed website, and in early twentieth-century English at Standard Ebooks in a translation by the little-known Cambridge classicist V. S. Vernon Jones. According to the Greek in Perry’s edition, a partial screenshot of a facsimile of which is provided below, the fable shows that “many human beings harm themselves in their rivalries”:

But another lesson appears to me quite clearly deducible: some things are bound to fall.

Beginning this essay with “The Tortoise and the Eagle” was not a purely arbitrary or self-referential choice, but an attempt to clear the way for the reader to see my point about something quite different, something indisputably a matter for adult and perhaps even scholarly consideration.

1.

The thing in question is the translation of the first line of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, first published in German in 1921 under the title Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung. As Wittgenstein died in 1951, the original text entered the public domain in 2021, and by 2025 three new English translations had appeared. For perspicuity and later reference, below is the first line in its original language, followed by various translations of it, mostly into Indo-European languages.

Wittgenstein:

Die Welt ist alles, was der Fall ist.English translations:

Ramsey-Ogden (1922): The world is everything that is the case.

Pears-McGuinness (1961): The world is all that is the case.

Beaney (2023): The world is everything that is the case.

Searls (2024): The world is everything there is.6

Booth (2025): The world is all that happens to be the case.Other Indo-European translations:

Dutch: De wereld is alles, wat het geval is.

French: 1: Le monde est tout ce qui a lieu.; 2: Le monde est tout ce qui est le cas.; 3: Le monde est tout ce qui se produit là.; 4: Le monde est tout ce qui advient.; 5: Le monde est tout ce qui arrive.

Icelandic: Heimurinn er allt sem er.

Italian: 1: Il mondo è tutto ciò che accade.; 2: Il mondo è tutto ciò che si verifica.

Modern Greek: Ο κόσμος είναι όλα όσα συμβαίνουν.

Portuguese: O mundo é tudo o que ocorre.

Russian: 1: Мир — это все, чему случается быть.; 2: Мир есть всё то, что имеет место.

Spanish: 1: El mundo es todo lo que acaece.; 2: El mundo es todo lo que es el caso.Non-Indo-European translations:

Hungarian: A világ mindaz, aminek esete fennáll.

Finnish: Maailmaa on kaikki, mikä on niin kuin se on.

It would be interesting to conduct a comparative investigation of the nuances of the various English and non-English renderings. Lacking the relevant expertise, I cannot attempt to do such a thing; the translations are intended to serve mostly as a reminder that there are many more renderings that might be considered than just the various English ones, even without leaving the comfort of our own language family.

That reminder is necessary, because it is the relation between the English and German versions to which I am admittedly concerned to devote my attention in this short essay. In particular, there is a claim concerning the difficulty of translating Wittgenstein’s sentence into English about which it is my aim to raise a question.