“Why hath the unicorn but one horn?”

Keynote Address in Memory of Balthasar von Cyr (1906-2024)

Delivered at the Annual Meeting of the Société Européenne des Études Altaïques, Université Paris XVII — Guilhem Bélibaste, February 24, 2025.

1.

It is a great honor to speak to you this afternoon, and to see this enormous amphitheater filled to capacity. We Altaicists must never become complacent about the tremendous growth of our field of specialization in Europe and America in recent years. It is gratifying indeed to see what a great number of people, especially students, are eager to learn more about the values, practices, and mental representations that have shaped the life-worlds of the peoples of the Eurasian steppe.

Just this past semester I had to cap enrollments in my “Introduction to Pumpokol” course at 75 students — and even then dozens of “shoppers” insisted on coming, sitting on the floor, begging me afterwards to check and see whether any of the pre-enrolled students had ended up dropping. Our universities are healthy indeed, and especially the humanities. And among these it is hard not to feel, at least from my perspective as a career-long insider, that Altaic Studies is the healthiest of them all. Truly, it warms an old Altaicist’s heart. What a wonderful time to be a student of the dazzling diversity and richness of the human story!

I have been invited to give the keynote address today, let us be frank, not in view of my own scholarly accomplishments, but only because I was the last doctoral student of the great Balthasar von Cyr, whose life and work we are gathered here this week to celebrate. It is not false modesty when I say that this pretext for my address is one that I cherish far more than if we were gathered here to celebrate my own work instead. I must note however that in the coming years it will grow increasingly difficult for me to determine with any precision where his work leaves off and mine begins. For as some of you will already know, shortly before he died in August of last year, just shy of his 118th birthday, Professor Doktor Freiherr von Cyr designated me as his sole executor, and asked me to complete a number of the projects he had been pursuing at the moment of his untimely demise. This is a charge I happily took on, and today I propose to speak to you, after a brief biographical introduction to his life and work, on one of the most promising of these projects, to wit, his radically revisionist account of the origins of the pan-Eurasian mythological figure —or is it only a mythological figure?— of the unicorn.

2.

All of you will surely already know something of the remarkable life of Balthasar von Cyr, and it is likely that at least part of what you know, but only part of it, is true. Of both French Huguenot extraction and Baltic-German nobility, von Cyr was born in the Governorate of Estonia in 1906, and grew up primarily on his family’s manorial estate at Pernauwald. It is true that his younger sister Edwige (1910-1968) was confined to the Irrenanstalt at Dorpat from the age of 10, having become convinced of herself that she was a carrion crow, with the most awkward consequences for her social comportment. But the explanation that has long circulated of the causes of her insanity is nothing but a scurrilous rumor, one that I will not even deign to make explicit here, let alone to refute.

With the possible exception of the Kaali stone, today no confirmed examples of Finnic runestones are known to exist. Yet according to von Cyr’s own account, at the age of 13, when he was out playing with his bloodhound Plekk in the woods near Pernauwald, he came upon an object that would change his life — a small piece of granite that appeared to represent the pre-Christian deity Ukko, hurling a lightning bolt, surrounded by several non-representational markings of an unknown alphabet or Futhark. By the age of 16, von Cyr was in correspondence with the most prominent Finno-Ugricists of Dorpat and Helsinki, and by the following year he had published his first scholarly article: “Über den altfinnischen Pernauwalder Runenstein,” Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen, Sonderhefte, Reihe VI, Band 4 (1923): 296-307.

Enamored of the most extreme formulation of the then-fashionable pan-Turanist theory, which posited an ancient unity not only between the Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic languages, but the Finno-Ugric and even the Japonic languages as well, in 1925, at the age of 19, von Cyr left for Berlin to begin his studies in comparative Turkology under the direction of Otto Jastrow, at the Institute for the Study of Oriental Languages of the Humboldt University. Over the next five years, he established himself as one of the most important researches in Eurasian linguistics and ethnology in the broadest sense. In 1933, only 28, he became the youngest person in the history of the Humboldt University ever to occupy a Lehrstuhl, and was renowned for his lively lectures on everything from the morphosyntax of Old Karelian to the soul-as-bird motif in Buryat representations of the afterlife.

And von Cyr no doubt would happily have stayed in this arrangement for the rest of his life, had history not got in the way. In 1941 he was conscripted into the Wehrmacht to serve as an intelligence officer on the Eastern Front. In particular, his primary duty was to interrogate captured Red Army soldiers of Volga Tatar origin in their own language. The circumstances of his own capture are unclear, but we know that he was himself taken prisoner somewhere in Bashkortostan, in the chaos of Operation Barbarossa in early 1942. Some say he surrendered intentionally, and made the surprising request of his captors to be sent to the notorious Kolyma prison camp. It is conjectured that he negotiated relatively comfortable terms for his imprisonment by offering to eavesdrop on his Evenk and Yukaghir cellmates, who naturally could never suspect that he might understand what they were saying.

I suspect that this story is true, but that von Cyr always did his best, under difficult circumstances, where inevitably some moral compromises had to be made, to play a double game — revealing just enough information to his guards to be able to maintain his favored status, while striving never to betray the real conspiracies and escape plots that his mates were actively devising in their little-known tongues. I also believe that the other great rumor about his time in the USSR is true: that he declined —nay, refused— to be released from the GULag during an initial round of prisoner exchanges in 1948, and ended up remaining until 1956, the year he turned 50, for the sole reason that he had initially been dissatisfied with his degree of competency in Chukchi, and hoped that a longer sojourn in Kolyma might help him to perfect it. This was a man, we may confidently say, with uncommon priorities.

Upon his arrival in West Germany, von Cyr experienced some difficult years. The de-Nazification tribunals had ceased operation by 1953, and von Cyr faced no official professional ban, yet he suspected nonetheless that his activities during the war largely explained his inability to find an academic post. In spite of growing interest in his work in the United States, his numerous visa applications consistently failed to gain approval. Perhaps even more disastrously, his analysis of the Pernauwald runestone had by now been exposed as completely erroneous: the markings on the granite, as a team of East German scholars decisively proved in 1961, were “but ordinary taphonomic grooves and fissures, along with some hasty additions, most likely carved by a pocketknife.” Von Cyr’s breakthrough work, it was now claimed, “was nothing but a teenage prank [nichts anders als ein Jugendstreich]” (F. W. Görke et al., “Der Pernauwalder Runenstein: Eine Neubewertung der von Cyr’schen Hypothese,” Archäologische Nachrichten aus dem Osten 4/1 [Herbst, 1961]: 89-114). Among the more famous lines for which von Cyr is today remembered was his acerbic response in a letter published in the following issue of the same journal: “My fake scholarship is still better than their real scholarship”. Personally, this is a dictum whose deep wisdom only reveals itself little by little as I advance in my own career.

Von Cyr did eventually obtain a post at the University of São Paulo, where he spent many productive but melancholy years, teaching in a language, as he often confided to me, for which he had “no natural feeling”. When I arrived in Brazil to begin working with Balty for my doctoral studies in 1994, he was not yet even ninety, and was in the most active, indeed frenetic, period of his career. He was demonstrably proficient in over 50 languages, and no doubt there were more for which he never bothered to provide a demonstration.1 What an opportunity that was for me! How grateful I am to have been trained under his wise guidance, and to have absorbed, as if by emanation, even just a small part of his endless knowledge.

But enough of these reminiscences. Let us return to the unicorn.

3.

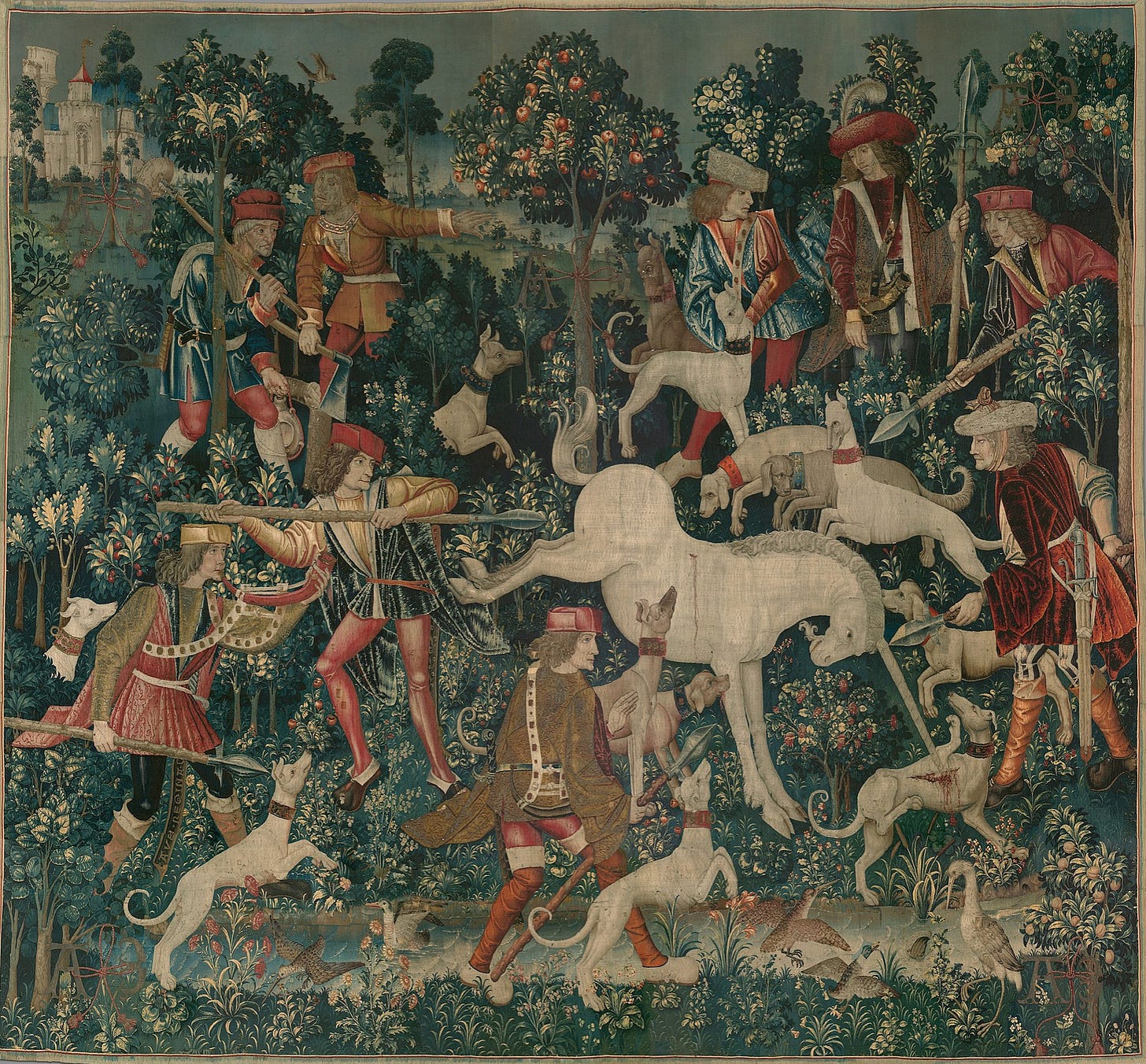

You likely suspect that the title of my keynote today has something to do with a treatment of analytic truths in the Kantian sense. How, you might be asking, could a unicorn fail to have one horn? We’ll leave that problem to the philosophers; my interest, like my mentor’s, lies elsewhere — with the Unicorn Tapestries currently hanging at the Cloisters in Upper Manhattan, for example.

You will know that this set of seven tapestries is the work of an unknown French artisan or collective of artisans, and dates from around the turn of the 16th century. They depict various scenes of the pursuit and capture of the mythical beast, in luminous colors of weld, madder, and woad. The most famous of them is no doubt the Seventh Tapestry, the Unicorn in Captivity, which scholars have generally identified as a variation on the Hortus conclusus or “enclosed garden” theme. Of more interest to us is the fragmentary Fifth, The Unicorn Surrenders to a Maiden, in its late echo of the common medieval trope according to which, as Leonardo da Vinci himself wrote, the love the unicorn bears for virgins causes it to “forget its ferocity and wildness; and laying aside all fear it will go up to a seated damsel and go to sleep in her lap, and thus the hunters take it.”

There are significant Biblical and allegorical dimensions here, but they need not detain us. The more important question for our purposes is to determine why one should wish to hunt the unicorn in the first place, and indeed should be so intent on capturing it as to use a human virgin, the most precious resource of any traditional society, as its bait. The unicorn, after all, is generally held to be a variety of horse, an animal that was first domesticated around 3500 BCE, and whose wild counterpart has not been widely hunted in Europe since at least the Iron Age. To hunt a horse, then, even a very special sort of horse, clearly involves a rupture with the ordinary rules governing the separation of the savage and the domestic, and likely also a symbolic substitution for another real animal that remained, and remains, a familiar target of hunters — to wit, the deer.

Thus the important question, once we have recognized this substitution, is to determine how and why the two horns of the real animal in question came to be reduced to one. But in order to make complete sense of this reduction, or as it were this unification, we will need to move far outside the world of Renaissance French tapestries, and into the sphere of cultural representations to which I, and my mentor, whose work I am here continuing, have devoted our careers.

The great Altaicist Jean-Paul Roux —a friend and collaborator, and frequent scholarly rival, of our own Balthasar von Cyr—, well summarized the prevailing theories of the nature and origins of the unicorn throughout the Altaic Kulturgebiet (see his magisterial Faune et flore sacrées dans les sociétés altaïques, Paris, Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1966). There are, he argues, two principal accounts: that the unicorn is a variety of rhinoceros, and that it is a horse with an unusual growth on its face.

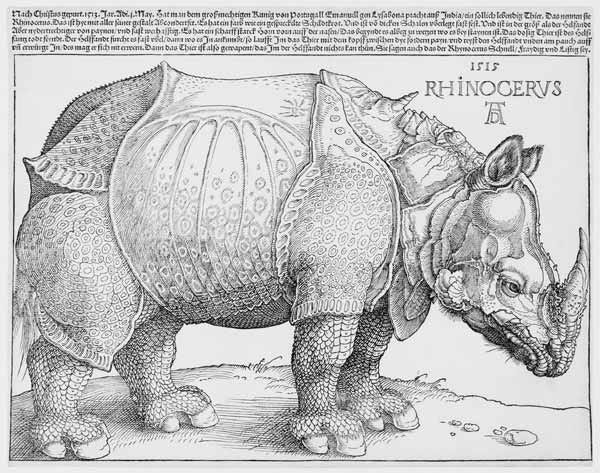

The “rhinoceros theory” would seem to be a classical instance of the universal cognitive habit of assimilating the unknown to the known, which left the first European explorers of the Americas convinced that there were, in that hemisphere, not only lions, but also, notably, corn. Marco Polo himself gave us an instance of such assimilation when he identified the Sumatran rhinoceros as a sort of unicorn — if not quite the sort he may have hoped to see. But if in this case there is an assimilation of the unknown to the known, the question is only punted one step further, and we must still ask how it is, in the first place, that the unicorn became known.

Roux’s analysis shows that for the Altaic languages with a distinct term for the unicorn, in every case the term is a borrowing —from Chinese, Tibetan, Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit— of a word that in its original meaning designated the rhinoceros. In the 10th century, Ahmad ibn-Fadlân provided an extensive account of a Central Asian animal that is “smaller than the camel, larger than the bull. Its head is the head of a camel, its tail the tail of a bull and its body the body of a mule. Its claws resemble the hooves of a bull. It has, in the middle of its head, a single horn, thick and round.” The Arab explorer adds: “Some of the inhabitants of the country maintain that it is a rhinoceros.”

We likewise know of a surprisingly similar, if rather more colorful, description from Manchu sources of what can only be the same beast: “It has the body of a buck, the tail of a bull, the head of a sheep, the legs of a horse, the hooves of a bull and a single horn that is fleshy at its tip. Its body is of five different colors. Its height is twelve feet” (Erich Hauer, Handwörterbuch der Mandschusprache, Wiesbaden, 1955, p. 586).

As Roux astutely notes, “we are far here from the primitive rhinoceros”. He speculates however that something rather more complex has occurred in these variations than what we have in the Venetian explorer’s Sumatran assimilation in the example already cited. “The unicorn,” Roux writes, “built from the parts of various familiar beasts, becomes a hybrid that is hardly distinguished from all the other hybrids we find in Altaic mythology.” This in turn is a confirmation for him of a general pattern in Altaic representations of nature, in which the souls of all humans, animals, and plants are conceived as sharing in fundamentally the same essence, the qut or the life-force, and therefore we are more likely to find recombinations of the known parts of real species, than “the representation of fantastical and entirely imaginary animals” that would stand outside of the known order of things, and therefore would be presumed to be possessed of a different order or quality of soul, if they were to exist.

The unicorn in the Chinese and European traditions by contrast is not just an ordinary chimera. It represents not a reassemblage of parts, but perfection, perhaps even transcendence. In Europe, this quality motivates an ever-intensifying medieval assimilation of the animal to Christ, a process that perhaps culminates in the Unicorn Tapestries themselves. In the Altaic sphere, by contrast, Roux contends, the unicorn is but a weakened signal: borrowed from neighbors who understood its perfection, only to be progressively degraded into a mere oddity.

The second theory, which we may call “teratological”, is even more dismissive of the importance of the unicorn for Altaic societies. Roux highlights a key passage of the Secret History of the Mongols, in §117, where Jamuqa gives to the young Genghis Khan a “horned horse”. The great Belgian scholar and Catholic missionary Antoine Mostaert observes, in a rather positivist vein, that “it’s plainly not a matter here of a real horn”, and adds: “I myself saw a horned horse among the Ordos [people of Mongolia]. Its horn was a keratinous cylindrical excrescence, several centimeters long, protruding from its temple; they called him ‘the horned russet’” (“Trois passages de l’Histoire secrète des Mongols”, Studia Orientalia v. 14, no. 9 [1950]: 4-6).

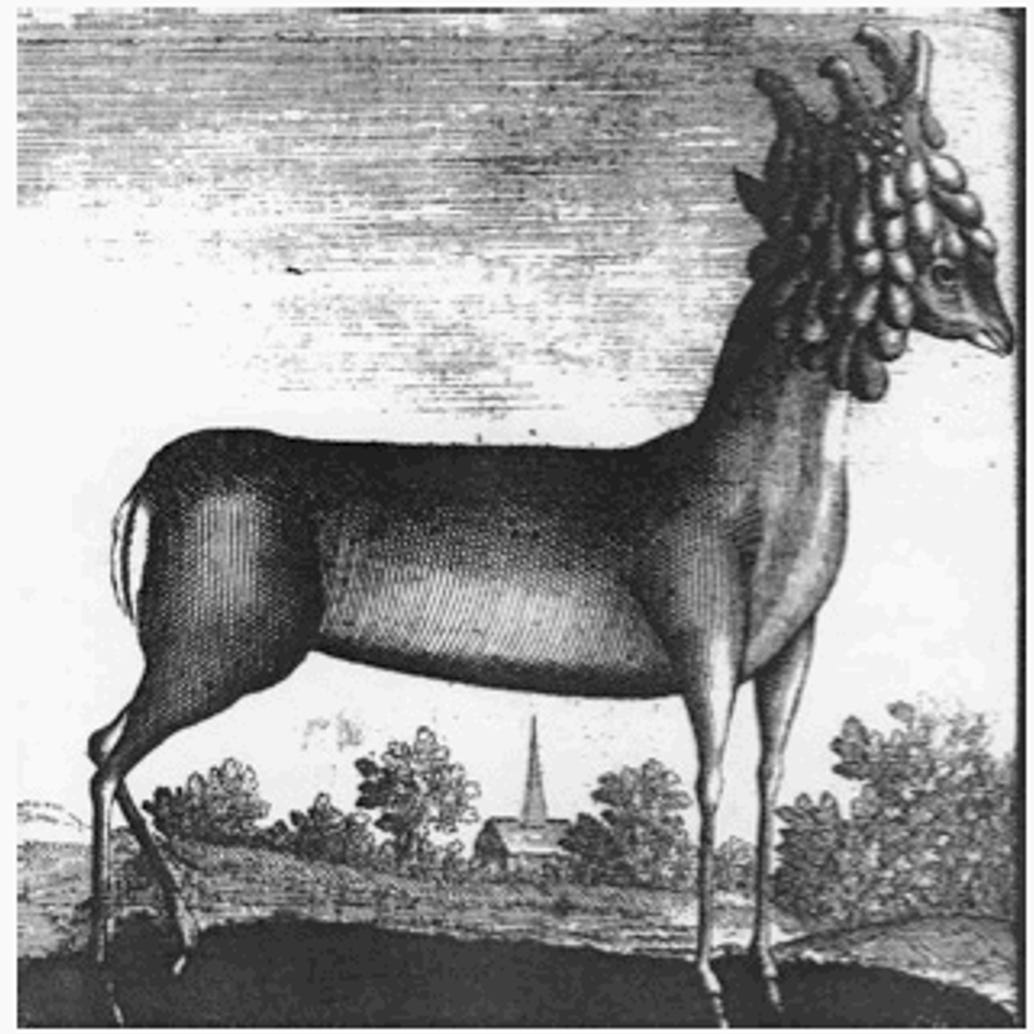

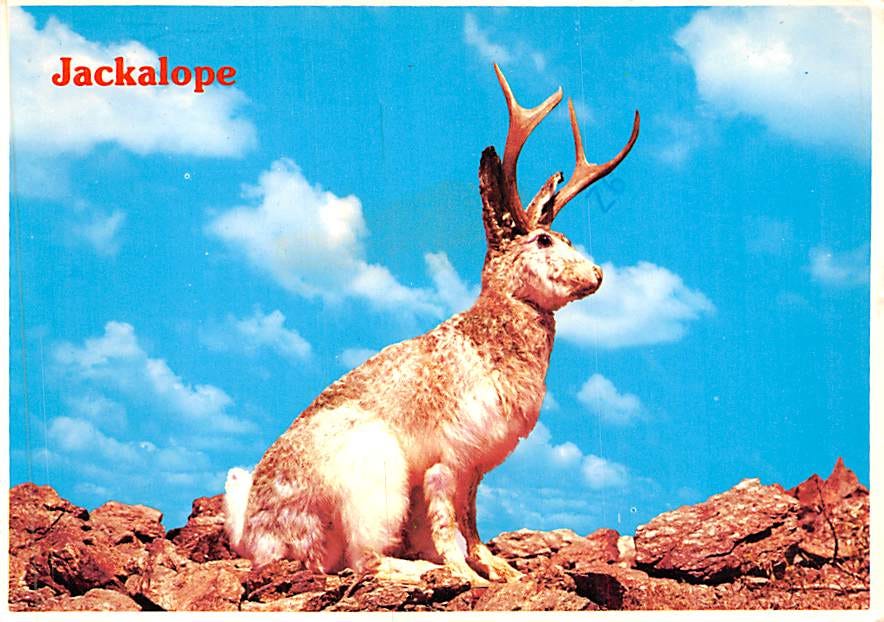

Some of you will be reminded here of our own great Leibniz, no minor Altaicist in his own right, who in 1677 trekked out to the German countryside to investigate reports of “a stag with a most extraordinary coiffure”, only to conclude that “the physical cause of this excrescence could be attributed to the fact that the aqueous humor of this animal could not be dissipated as soon as it was attached, as it ordinarily is by the heat... that is accumulated in their bounding, leaping, and running” (G. W. Leibniz, “La Rélation, et la figure d’un Chevreuil coëffé d’une manière fort extraordinaire,” Journal des Sçavans [5 juillet, 1677]: 166-68). We might also add here the common maneuver, among more skeptically minded inhabitants of the High Desert of the American West, in which reported sightings of the jackalope are deflated by appeal to the facial tumors sometimes found on the black-tailed jackrabbit. In all cases, there is a concern not only to explain the causal histories of mythological beings, but more than that, to be done with them. Such impatience, to say the least, never characterized von Cyr’s approach to these matters, and so it is only appropriate that we move on as quickly as we can from the teratological theory.

What we discover when we abandon the crude positivism that dominated over the course of the 20th century, from which even Roux was not able entirely to free himself, and which often kept our own von Cyr relegated to the margins of his own discipline, is not so much that the Altaic unicorn is as perfect or transcendent as the European or Chinese instances of it, but rather that it reveals a dynamic cultural process within the Eurasian steppe that itself led to the representations of the unicorn’s perfection at Eurasia’s margins.

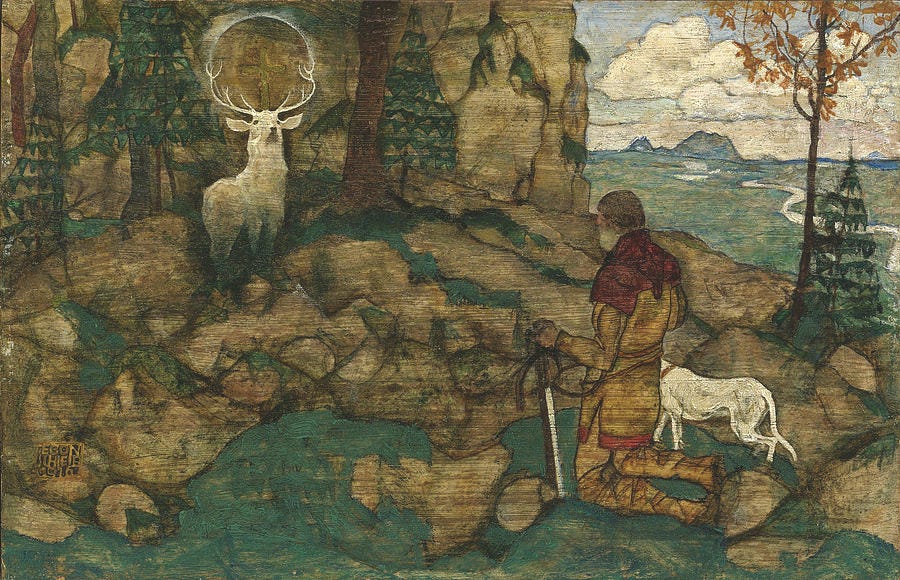

In order to see this, we must look much further back in history than Roux’s written sources, to the Iron Age burial mounds of the Scythian-related archaeological culture known as the Pazyryk. As you will likely already know, excavations of numerous Pazyryk kurgans from the 6th to the 3rd centuries BCE have revealed well-preserved horse burials, in which these animals were equipped with elaborate ceremonial tack, including headdresses featuring stylized wooden or felt deer antlers. There is some evidence as well that not just in burial, but also in mounted combat, Pazyryk warriors adorned their horses with real deer antlers as they rushed into battle. But why dress your horse up like a deer? Why, more particularly, would the members of a solidly horse-centric culture symbolically represent these exalted creatures to themselves as forest-dwelling game animals?

Here is where we arrive at the crux of the matter, and rather than offering you my own further elaborations of the project delegated to me, I believe it will be most appropriate now to quote from the unfinished, and indeed sometimes fragmentary, notes that von Cyr handed over to me on this question that so occupied him in his final years. “Why hath the unicorn but one horn?” he asks in an undated text, in difficult handwriting and unexplained archaic English, at the top of the front page of a lined Leuchtturm notebook. And he continues, in imperfect but serviceable Portuguese2:

In order to answer this question we should first gain some clearer understanding of what a horn is. Among our first observations, we should note that horns are, almost without exception, a marker of bilateral symmetry. The swordfish has a “sword”, almost as if its singularity, more than its non-keratinousness, disqualifies it from any other designation. The lately discovered narwhal has a “tusk”, and even if we stretch and call it a horn, as Ole Worm tried to pass it off in his Copenhagen Wunderkammer, we must note that neither of these is quite correct. It is in fact an overgrown tooth, either the left or the right front tooth —it remains a great mystery of science, perhaps the greatest of them all, why it should be the one or the other—, and thus an instance of extreme deviation from the symmetry that has characterized our lineage since the time of the pre-Cambrian Urbilaterian. This leaves us with at least some species of rhinoceros as the closest we have to a real-world candidate for possession of a single central horn, which, as if to prove nature’s sense of humor, comes attached not to a noble beast like the horse, but to a strange and almost comical creature that even an eye as generous as Dürer’s could not but represent as an armor-plated battle-tank.

The horse is the animal that should have had a single horn, if any should have. We looked at our horses’ barren foreheads and felt horn envy on their part. The psychoanalysts saw the unicorn’s horn as a frontal counterpart of the tail, and the tail as a dorsal counterpart of the phallus, which explained why the creature was so intent on laying his head in the lap of the virgin. But all that was a distraction. And again in order to see this we need to be prepared to treat the equid and the cervid as constituting an inseparable symbolic pair for at least several millennia of Eurasian history.

There is indeed a possibility we have not yet considered that can help us to bring this pairing into clearer relief: not the one-horned, not the two-horned, but the three-horned animal. I have in mind of course not the triceratops, which besides Adrienne Mayor and a few other scholars can be presumed to have played no role at all in human cultural history. I have in mind rather the deer seen by St. Hubert when, prior to his great repentance, he went out hunting of a Sunday. That deer, you will recall, had a glowing cross between its antlers. A cross is not a horn, you will say. But then again, when a horn appears on the forehead of a horse, what else does it symbolize, at least in the European variants of the unicorn myth, but Christ himself? Sometimes, we may at least say, a horn and a cross end up doing the same symbolic work.

St. Hubert’s stag, I mean, represents an intermediate stage of the unicorn, when the central horn is already there, but the outer horns, or antlers in this case, have not yet fallen away. This intermediate stage likewise plainly demonstrates the cervid-to-equid continuity in Eurasian cultural history, a more archaic form of which we see plain as day in the Pazyryk kurgans.

The Freudians were not entirely mistaken to think about horns in terms of “anxiety”, but the source of this anxiety was consistently misidentified. It had much less to do with human sexuality, than with human-animal cohabitation. We simply never could quite come to terms with what was in the end a great crime, perhaps the greatest crime ever committed in the history of humanity — that of reducing our equals, the animals, to subjects, now dominated entirely by our human will and whim. This, as the steppe peoples continued to understand long after their fully sedentized neighbors to the East and West had forgotten, was the true Fall.

But even after the Fall the deer continued to lurk in the forest just beyond our settlements, as the non-sheep, the non-cow, and above all the non-horse. It is not surprising, then, to find enduring efforts to honor the horse, to exalt it, by making it symbolically into a deer again. And as the universal religions of Christianity and Islam interrupted the traditional cults of reverence of animal spirits in favor of a transcendent Creator and Savior, over time, again at least in the Western elaboration of this historical process that began in the steppe, the deer became more than a deer, but a symbol of embodied perfection — in other words the unicorn; in other words the Christ.

4.

I sincerely wish I could elaborate further on these reflections from my mentor, but the truth is I am not yet certain I have fully understood them, nor am I blind to the fact that the amphitheater is not quite as full as when I began this keynote address. So allow me now, somewhat off the cuff, to conclude by reading to you in turn a curious note found on the final page of the same Leichtturm notebook. This note may help us better to understand a chapter of von Cyr’s life that, I realize, I said at the beginning I would not deign to discuss, but that I now intuit is likely to keep those of you remaining in your seats until the end. More than that, it’s likely to make you feel a sudden keen need for a drink, so I do hope you’ll join us at the reception in the foyer afterwards [scattered nervous laughter].

To conclude, then, Balthasar von Cyr writes3:

What no one understood is that she really was a crow. Edwige was a crow. Souls still become birds, sometimes. People have forgotten, but souls still become birds. Usually they become birds and fly away, but Edwige stayed.

That’s what set me down this path in life. The runestone was just a pretext. Alright, I admit it: it was a juvenile prank. What I really wanted to understand is what I already witnessed at a very early age in the person closest to me in the world, and that some faint intuition told me our ancestors had always known.

I have said souls become birds, but it would have been more correct to say that souls are birds, or that they are “ornithomorphic”, as scholarly norms required me to put it for so many years. We have some faint hints of this plain fact in our banal folktales — as when the stork is said to “deliver” the baby. The stork is not a common deliveryman, however, but a vehicle of the preexisting soul.

And as in birth, so in death: the soul flies away.

The soul flies away — but Edwige stayed.

Thank you for your attention. I’ll see you outside for that apéro.

—

Edwin-Rainer Grebe holds the Ewald R. and Ethel P. Grundy Chair in Altaic Studies at Harvard University.

In rough order of acquisition: German, Russian, Estonian, French, English, Finnish, Swedish, Lithuanian, Latin, Greek, Polish, Sanskrit, Turkish, Latvian, Hungarian, Japanese, Korean, Persian, Ottoman, Avestan, Tatar (Volga and Crimean), Gothic, Mongolian, Uighur, Chuvash, Old Turkic, Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkmen, Karakalpak, Sakha, Dolgan, Nenets, Mordvin, Udmurt, Sami, Khanty, Komi, Mari, Veps, Karelian, Gagauz, Kalmyk, Ket, Navajo, Ainu, Aleut, Nivkh, Koryak, Itelmen, Manchu, Buryat, Evenk, Yukaghir, Tibetan, and, finally, Portuguese. Curiously, Chukchi never made his personal list.

Para responder a essa pergunta, primeiro precisamos entender melhor o que é um chifre. Entre nossas primeiras observações, devemos notar que os chifres são, quase sem exceção, um marcador de simetria bilateral. O espadarte tem uma “espada”, quase como se sua singularidade —mais do que sua não-queratinização— o desqualificasse para qualquer outra designação. O narval, descoberto recentemente, tem uma “presa”, e mesmo que nos esforcemos para chamá-la de chifre, como Ole Worm tentou fazer em seu Wunderkammer de Copenhague, devemos observar que nenhuma dessas denominações está correta — na verdade, é um dente hipercrescido, seja o dente frontal esquerdo ou direito — e permanece um grande mistério da ciência, talvez o maior de todos, por que deve ser um ou outro — e, portanto, um exemplo de extrema divergência da simetria que caracteriza nossa linhagem desde os tempos do Urbilateriano pré-cambriano. Isso nos deixa com pelo menos algumas espécies de rinoceronte como os candidatos mais próximos do mundo real para possuir um único chifre central, que, como que para provar o senso de humor da natureza, vem acoplado não a um animal nobre como o cavalo, mas a uma criatura estranha e quase cômica que mesmo um olhar tão generoso quanto o de Dürer não pôde deixar de representar como um tanque de guerra blindado.

O cavalo é o animal que deveria ter um único chifre, se algum deveria tê-lo. Olhamos para as frontes desnudas de nossos cavalos e sentimos uma inveja de chifres por parte deles. Os psicanalistas enxergavam o chifre do unicórnio como uma contraparte frontal da cauda, e a cauda como uma contraparte dorsal do falo - o que explicava por que ele estava tão empenhado em repousar a cabeça no colo da virgem. Mas tudo isso era uma distração. E, mais uma vez, para enxergarmos isso, precisamos estar preparados para tratar os equídeos e cervídeos como constituindo um par simbiótico inseparável por pelo menos vários milênios da história eurasiática.

Existe de fato uma possibilidade que ainda não consideramos e que pode nos ajudar a traçar um paralelo mais nítido: não o animal de um chifre, nem o de dois, mas o de três chifres. Refiro-me, é claro, não ao tricerátopo — que, salvo por Adrienne Mayor e alguns outros acadêmicos, pode-se presumir não ter desempenhado nenhum papel na história cultural humana - mas sim ao cervo avistado por São Huberto quando, antes de seu grande arrependimento, saiu para caçar em um domingo. Aquele cervo, como vocês devem se lembrar, trazia uma cruz luminosa entre seus chifres. “Uma cruz não é um chifre”, vocês podem dizer. Mas, por outro lado, quando um chifre aparece na testa de um cavalo, o que mais ele simboliza — pelo menos nas variantes europeias do mito do unicórnio - senão o próprio Cristo? Às vezes, podemos ao menos dizer, um chifre e uma cruz acabam cumprindo a mesma função simbólica.

O cervo de São Huberto, quero dizer, representa um estágio intermediário do unicórnio, quando o chifre central já está presente, mas os chifres externos - ou galhadas, neste caso - ainda não caíram. Este estágio intermediário também demonstra claramente a continuidade cervídeo-equina na história cultural eurasiática, uma forma mais arcaica da qual vemos com toda clareza nos kurgans de Pazyryk.

Os freudianos não estavam completamente errados em pensar nos chifres em termos de “ansiedade”, mas a fonte dessa ansiedade foi sistematicamente mal identificada. Tinha muito menos a ver com a sexualidade humana do que com a convivência humano-animal. Simplesmente nunca conseguimos realmente aceitar o que foi, no final das contas, um grande crime — talvez o maior crime já cometido na história da humanidade — o de reduzir nossos iguais, os animais, a nossos súditos, dominados agora inteiramente por nossa vontade e capricho humanos. Isto foi, como os povos das estepes continuaram a entender muito depois que seus vizinhos totalmente sedentários no Oriente e Ocidente haviam esquecido, a verdadeira Caída.

Mas mesmo após a Caída, o cervo continuou a espreitar na floresta logo além de nossos assentamentos, como o não-carneiro, o não-boi e, acima de tudo, o não-cavalo. Não é surpreendente, então, encontrar esforços duradouros para honrar o cavalo, exaltá-lo, transformando-o simbolicamente em um cervo novamente. E quando as religiões universais interromperam os cultos tradicionais de reverência aos espíritos animais em favor de um criador transcendente, com o tempo — pelo menos na elaboração ocidental desse processo histórico que começou na estepe — o cervo tornou-se mais que um cervo, mas um símbolo da perfeição encarnada: em outras palavras, o unicórnio; em outras palavras, o Cristo.

O que ninguém entendeu é que ela realmente era um corvo. Edwige era um corvo. As almas ainda se transformam em pássaros, às vezes. As pessoas esqueceram, mas as almas ainda se transformam em pássaros. Normalmente elas se tornam pássaros e voam para longe, mas Edwige ficou.

Foi isso que me colocou nesse caminho na vida. A pedra rúnica foi apenas um pretexto. Tudo bem, eu admito: foi uma brincadeira juvenil. O que eu realmente queria entender era o que eu já tinha testemunhado muito cedo na pessoa mais próxima de mim no mundo, e que uma vaga intuição me dizia que nossos ancestrais sempre souberam.

Eu disse que as almas se transformam em pássaros, mas teria sido mais correto dizer que as almas são pássaros, ou que são “ornitomórficas”, como as normas acadêmicas me obrigaram a dizer por tantos anos. Temos alguns vestígios tênues desse fato simples em nossos contos folclóricos banais — como quando dizem que a cegonha “entrega” o bebê. A cegonha não é uma entregadora comum, porém, mas um veículo da alma pré-existente.

E assim como no nascimento, também na morte: a alma voa para longe.

A alma voa para longe — mas Edwige ficou.

Among your very most moving pieces.

St. Hubert! Ever since I first read his story, I've been baffled that I have yet to read anyone who references him, even among nature writers. (Though that could be because he's the patron saint of the hunter and the hound, who have become persona and canis non grata in environmental circles.)

All this aside, the whole span of where this story managed to go is a delight.